Topic: Data Management, Analytics & Visualization

Data Management, Analytics & Visualization

This page features information on managing and maintaining your data. Whether you want to monitor data

more effectively, bolster your data collection systems, or improve your data modeling, you can find what you need here.

Overview:

Transportation asset management is by its nature a data intensive activity. State DOT’s and other transportation

agencies are facing increasing pressures to do more with their limited TAM resources. Whether you want to monitor

data more effectively, bolster your data collection system, advance your data modeling, or improve your data-driven

communication, you can find what you need here.

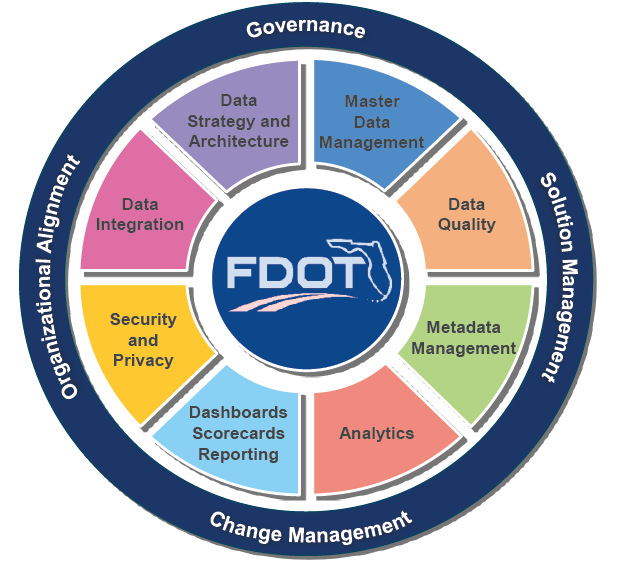

Defining Data Management

Data management is the set of activities carried out to manage data across its lifecycle. Data management activities

include data governance, planning and specification, data collection and documentation, data organization and

storage, data sharing and use, as well as data disposition.

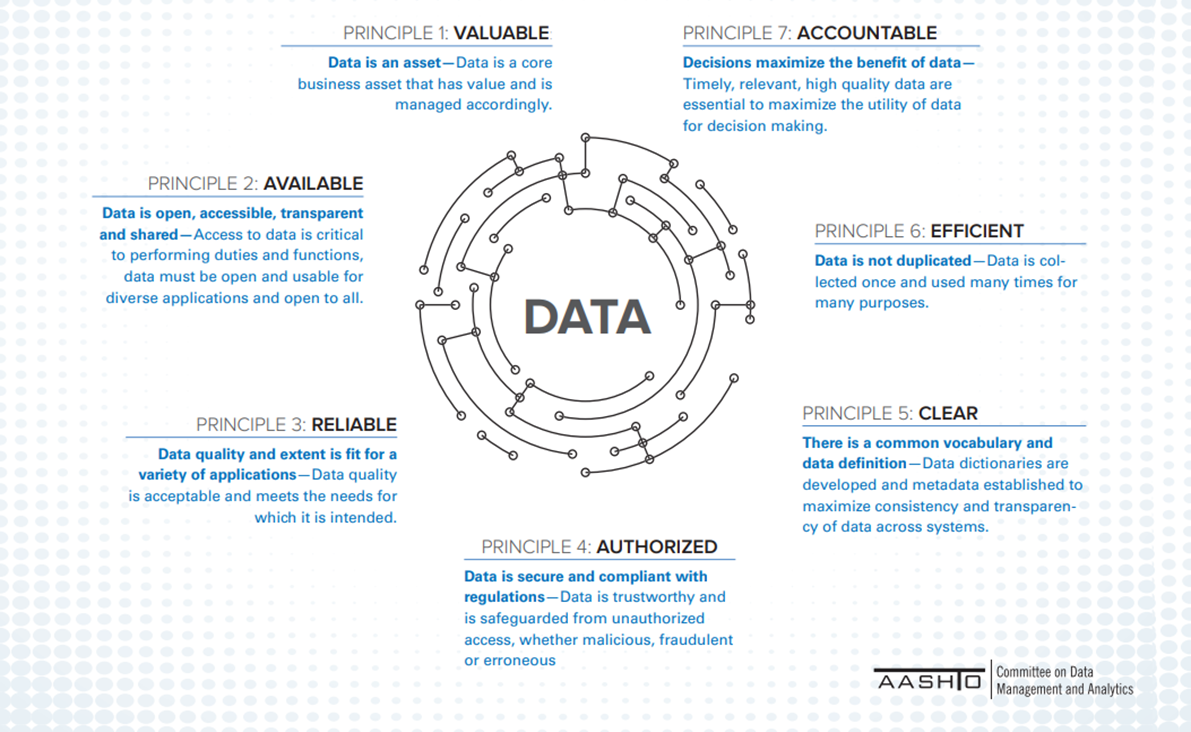

To support robust data management, AASHTO has established a set of seven Core Data Principles. You are encouraged to

consider and adopt these principles as you work to advance your agency’s data management and use.

As DOT TAM programs have grown increasingly complex and data rich, the need for effective data analysis and

visualizations has never been greater. Data analysis and visualizations are integral to how a modern TAM program

drives results and decisions and shares insights with stakeholders. These practices have also never been more

accessible; many DOT’s are integrating powerful, configurable business intelligence and analytics tools into regular

use across their agencies. However, crafting succinct, engaging, powerful analytics and illustrations is a

challenge that is not solved by data and technology alone, effective practices are required to recognize your

audience and purpose, to select an appropriate visualization type, and deliver an effective, easily interpreted

topic.

Implementation Considerations:

TAM practitioners have a vital role to play in their agency’s data management programs and processes. As leaders and

subject matter experts in critical agency business areas, you should partner with data program leadership and

technical staff to support data value and use throughout its lifecycle. Key areas for business attention include:

- Data Specification. Prepare for new or adjusted databases with consideration of how data will be used, paying

attention to ensure you can provide precise, unambiguous data specifications, aligned with agency data

standards. Also, avoid duplication of data that is already collected elsewhere. - Metadata Management. Coordinate with technical staff to document the business and technical context of your

data, necessary to support data understanding. - Data Security Management. Help prevent unauthorized access to or use of data by documenting intended uses of

your data and identifying private, confidential or otherwise sensitive data partnering with technical staff to

ensure appropriate access controls. - Data Quality Management. Work to ensure data is fit for purpose, defining business rules for collection, quality

processing, and use, measuring quality, and planning for improvement. - Reference and Master Data Management. Establish and use authoritative sources for shared data.

- Data Integration. Combine data from authoritative sources, in alignment with acceptable uses, to support

analysis, reporting and decision-making. Provide clear requirements for technical staff who support extract,

transform, and load scripts, and double check that outcomes are meaningful. - Data Retention Planning. Keep data for its useful life and as required, but eliminate unnecessary data when it

is no longer useful. - Data Use. Be cognizant of good data analysis and visualizations, ensuring data is used appropriately and the

intent and meaning of analytics and illustrations are clear to targeted audiences.

Related Subsections:

Information Management 2.2.4

Planning and Programming, Performance Management and Risk management are activities that form components of the asset management framework within an agency. They are necessary to manage the infrastructure portfolio, and the services it supports.

Asset management relies on good data and tools to guide investment decision-making. Indeed many agencies have a wealth of data about their infrastructure, but are challenged to leverage information to make better decisions. Information management is the discipline that delivers foundational capabilities for asset management results. Asset management systems connect inventory and condition with analytical capabilities to predict asset condition under various funding and action scenarios. Other information and tools allow for the ability to relate asset actions across assets and with other transportation areas, such as safety and mobility. This section provides a brief overview of information management and how it supports the implementation of the concepts discussed in this guide. More detail can be found in subsequent Chapters. Each section has been crafted to illustrate how data, information and analysis can be leveraged to create better outcomes, and enable agencies to improve how they deliver services.

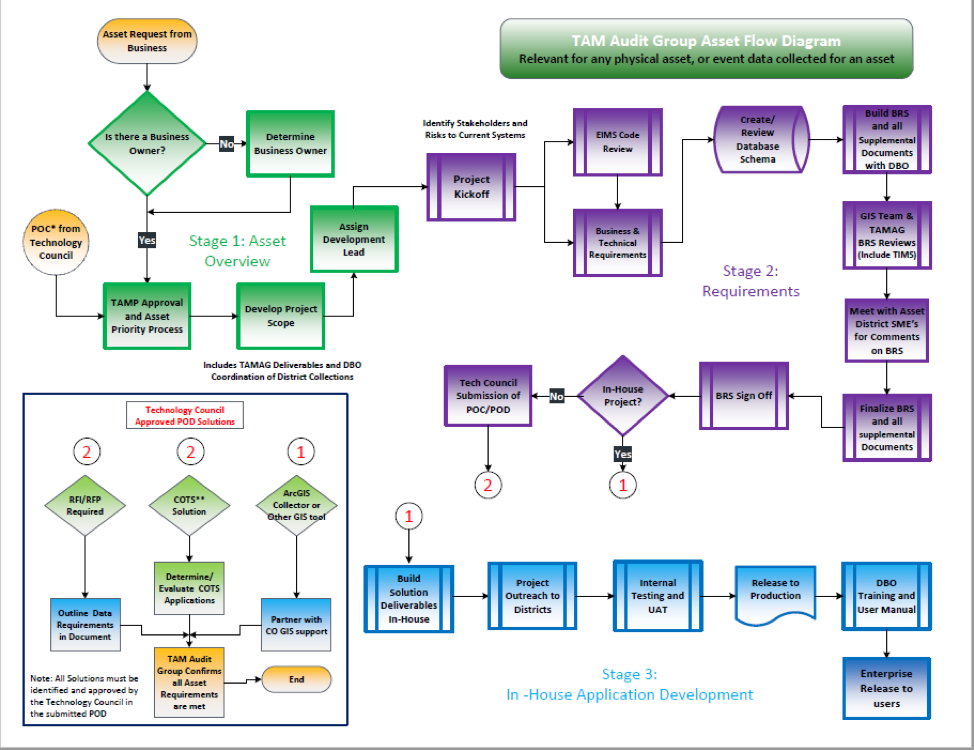

Data Collection Standards and Processes

Standards and processes for data collection are two important aspects of integrating asset management practices across the agency. Collecting a standard set of data elements for each asset ensures consistency, and better enables analysis and reporting across assets. Standard data elements can include a unique asset identifier, designated asset category and asset type. Geospatial referencing standards are also important. In order to see assets on a map and integrate them spatially, agencies need a standard way to locate them. It is also important to consider the data collection intake process. Before data is collected, agencies should determine if specific data already exists in order to prevent duplication. If the data does not exist and needs to be collected, agencies should consider how new data will integrate with what is available currently. This ensures the data is used in the most effective way possible. Finally, responsibility needs to be assigned to an Asset Data Steward who is responsible for ensuring data standards and processes are followed.

TIP

Data for asset management purposes can often be pulled from existing datasets that are used for other purposes. Alternatively, data collected for TAM purposes can often be used to fulfill other agency responsibilities.

Asset Information Across the Life Cycle

TAM integration also relies on collecting and updating asset information across the life cycle of the asset. It is important to think holistically about the asset life cycle, from the initial design phase and through future maintenance and rehabilitation activities. Technologies and processes are becoming available to extract asset information from design and as-built plans to populate inventories. Many agencies have processes in place to think holistically about assets during the project scoping and design phase.

Agencies face challenges in integrating asset information across the life cycle of the asset, because there is often a disconnect between maintenance activities, planning/ programming and the assets. For example, maintenance divisions may not know about planned projects on particular assets that have been scheduled for repairs. Better linkage between the work an agency is planning for the future, the work they are doing currently and the general condition of the assets is important to cultivate. Maturing agencies are working hard to bridge this gap. Chapter 6 provides more information on updating asset information and connecting with maintenance activities.

Common Set of Asset Management Reporting Processes

Another aspect of information management strategy that can help integrate TAM across an agency is to develop a common set of asset management reporting processes. Many agencies are successfully mapping different types of assets and making this information available on a GIS portal. Typically, these portals have different layers for each asset. This is one example of a consistent process for sharing information about assets.

As agencies seek to make cross-asset tradeoffs and scope projects considering multiple types of needs, having a common set of reporting processes and consistency across different tools becomes even more important. An example of the challenge agencies face in doing this is seen in the TAMP development process. Developing a TAMP requires information about the needs of different assets. This information must then be communicated with a common set of definitions and combined with funding information. Practitioners have to be aware of the funding and cost assumptions used in every tool before they can report numbers in the TAMP. For instance, the pavement management system might only include costs for the pavement work, whereas other planning tools might incorporate guardrail costs and other costs related to the work. Different tools might also use different assumptions for inflation. In order to bring all this information together in a TAMP, agencies need to make sure their reporting and assumptions are consistent.

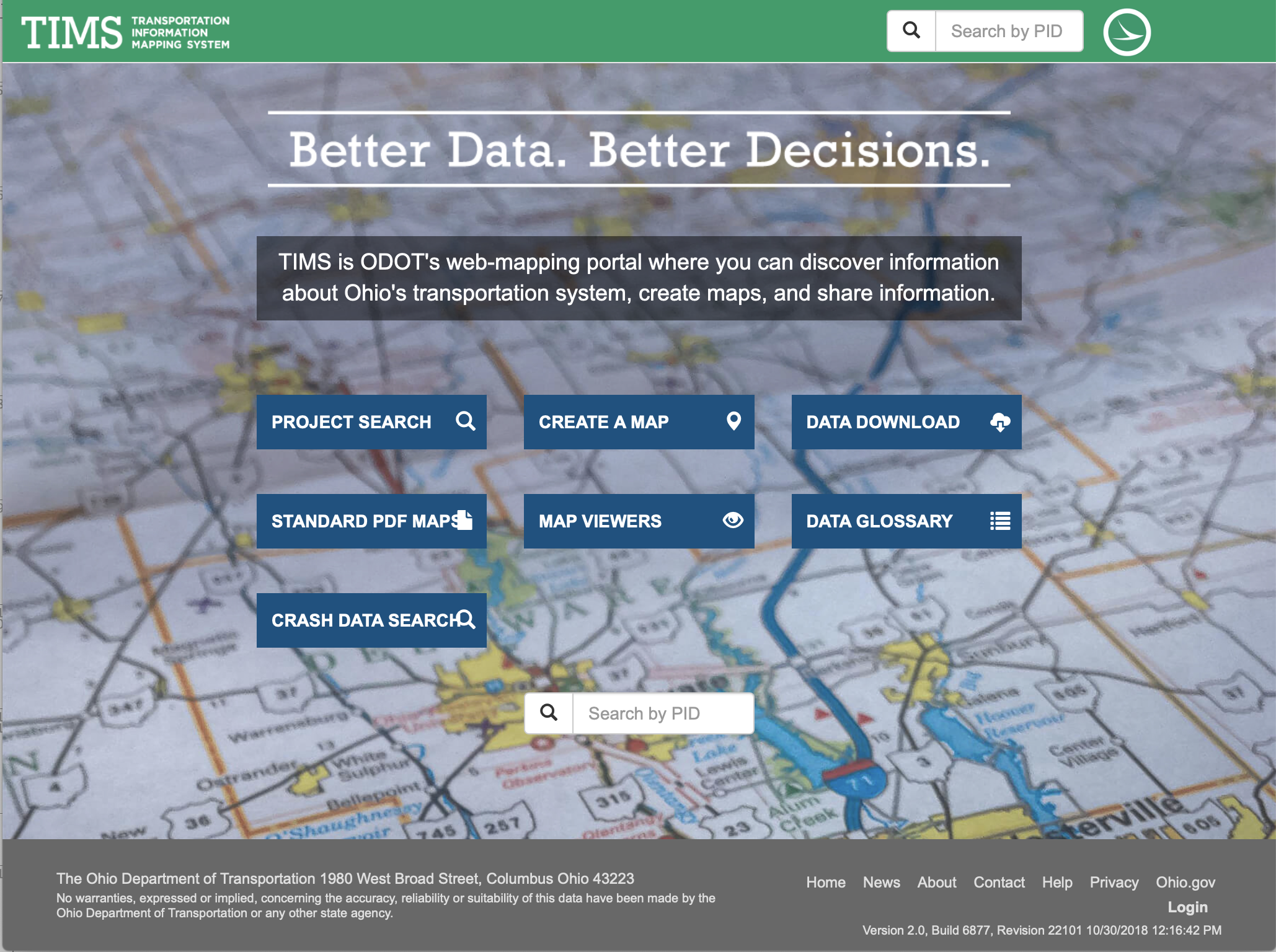

Ohio DOT

Ohio DOT (ODOT) has focused on data and information management improvements as a foundational element of their asset management program. As part of this they have strengthened their geographic information system (GIS) and linked it to over 80 data sets. The agency’s TIMS allows users to make collaborative decisions based on shared access to the same data sets.

Source: Ohio DOT. TIMS.https://gis.dot.state.oh.us/tims/

Beyond the Basic TAMP 2.4.2

This section contains suggestions for developing a TAMP that goes beyond the basic elements of a TAMP described in the previous section. An agency can expand the scope of the TAMP to include additional asset types and systems. An agency may further tailor their TAMP to address specific needs.

TAMP Scope

A highway agency focused on complying with Federal requirements will typically focus on including its NHS pavements and bridges in its TAMP. While these assets make up the greatest portion of a typical state highway agency, an agency may wish to include additional assets in its TAMP. Also, the agency may wish to extend the network scope of the TAMP. In updating a TAMP with NHS pavement and bridges, an agency may include other assets, such as drainage assets, traffic and safety features, or the agency may wish to include all of the assets it owns.

For transit TAMPs, the initial focus is on revenue vehicles, facilities and infrastructure, as these are the assets that require the greatest investment. An agency may wish to expand its TAMP to include additional assets that are important to the systems, albeit less costly, such as bus shelters and signage.

TAM Webinar #55 - TAM Tools Miniseries 02: Management Systems

TAM Implementation Plan

As described in Section 2.3, it is often helpful to prepare an implementation plan describing a set of planned business process improvements that an agency intends to undertake to strengthen its approach to TAM. There are many examples of TAMPs that focus specifically on an agency’s TAM approach and how it plans to improve its approach. Ideally a TAMP should both describe an agency’s assets and planned investments, and detail how it intends to improve its TAM approach. Where an agency has developed both a TAMP and TAM implementation plan, the implementation plan can be incorporated as a section of the TAMP.

TAM Guide Book Club #2: TAMP Implementation and Integration

TAM-Related Business Processes

An agency may wish to include a discussion of one or more of the business processes related to TAM in its TAMP. Alternatively, there may be other agency documents that provide more detail on these issues that can be referenced in the TAMP. These areas include:

- Performance Targets. As described in Chapter 5, setting performance targets can help guide the resource allocation process. However, agencies often have broader efforts to establish and track performance beyond the scope of TAM.

- Financial Planning. While developing a TAM investment plan is central to developing a TAMP, often the revenue forecast used to support developing the investment plan is developed separately and used for other purposes beyond the scope of TAM. It may be valuable to document the agency’s approach to forecasting future revenues for TAM and other applications. Chapter 5 describes provides additional detail on this topic.

- Work Planning and Delivery. As described in Chapters 4 and 5, work delivery approaches can impact how assets are maintained over their life cycle, and how resource allocation decisions are made. Some agencies have adopted formalized approaches for evaluating and selecting different work delivery approaches.

- Data Management. Chapter 7 discusses the importance of implementing an approach to data management and governance. Some TAMPs include additional information on this topic given its relationship to TAM.

AASHTO

The AASHTO TAMP Builder website (available at https://www.tamptemplate.org/) hosts annotated plan outlines to assist agencies in preparing TAMPs. The site also provides resources to customize an outline in order to meet agency-specific objectives and requirements. The website integrates a database of TAMPs, dating from 2005, that support the functionality of the outlines created using the site.

Use this Site to Build a MAP-21-Comlpiant TAMP

Data Collection 2.5.3

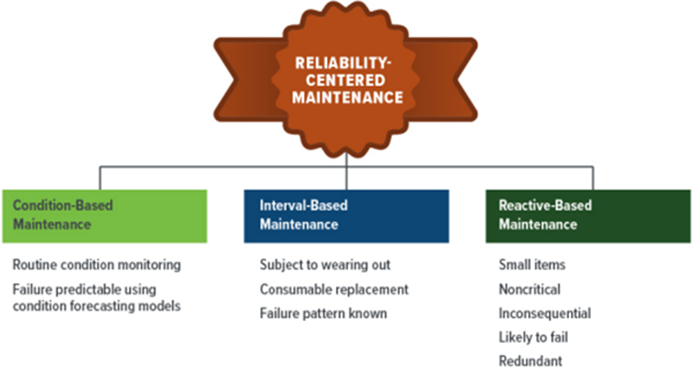

This subsection discusses the importance of data collection in asset management programs, emphasizing the need for coordination between different agency groups. It introduces a performance-based management strategy using the RCM approach, detailing condition-based, interval-based, and reactive maintenance components relevant to life cycle planning of ancillary highway assets. The document also provides a table summarizing maintenance approaches for various asset classes, supporting agencies in efficiently collecting high-quality data for informed decision-making.

After evaluating the priority of asset classes, asset stewards need to understand the intended functions, potential failure possibilities, available maintenance options, and the consequences of failure for each asset class. This information is typically dispersed across various areas or business units within an agency. Gathering this information necessitates coordination among different groups within the agency. The ideal approach involves following a framework to establish a performance-based management strategy for ancillary assets, identifying the optimal data elements for collection, and selecting the most suitable data collection techniques for each asset class.

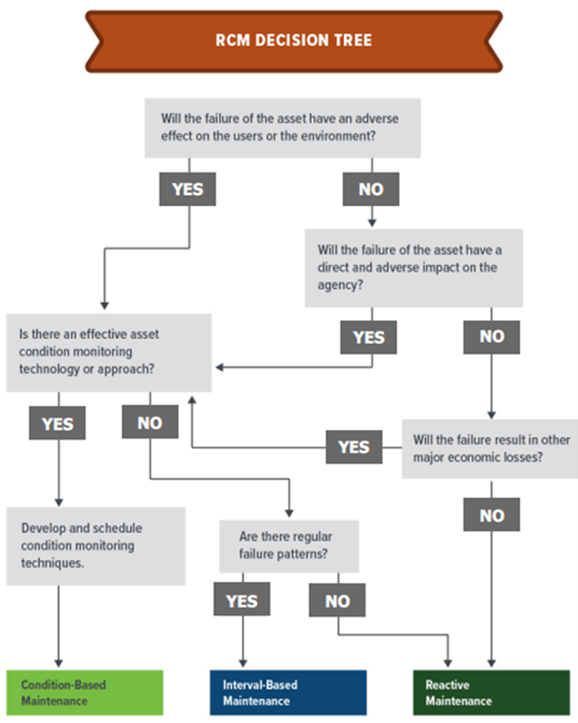

The Handbook (FHWA-HIF-19-006) offers a potential framework of interconnected processes that can be tailored to an agency's specific requirements. The process for developing a performance-based management strategy employs the Reliability-Centered Maintenance (RCM) approach, which is elaborated upon in Chapter 4. RCM utilizes a series of risk-based questions to assist agencies in identifying the most effective and efficient management strategies. The three primary components of an RCM program pertinent to the life-cycle planning of ancillary highway assets are condition-based maintenance, interval-based maintenance, and reactive maintenance. This is illustrated in Figure 2.12, as adapted in the Handbook from NASA (2008. Reliability-Centered Maintenance Guide for Facilities and Collateral Equipment. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, DC). A decision tree can be used to establish an appropriate management and maintenance approach for each ancillary asset class to inform data requirements. This is also illustrated in Figure 4.5 of Chapter 4.

- Condition-based maintenance includes predictive maintenance and real-time monitoring. Inspections note current capital and maintenance interventions as well as current state to be considered by maintenance teams and inputted into predictive models.

- Interval-based maintenance is conducted independently of the asset's condition and involves performing inspections or replacements at predetermined intervals.

- Reactive maintenance assumes that failure is low risk to operations and where there are no practical monitoring approaches and/or regular deterioration or failure patterns. Repairs are made after the failure. Table 2.4 presents a summary of the applicability of condition, interval, or reactive maintenance for each of the asset classes.

Table 2.4 Typical Maintenance Approaches by Asset Class

| Asset Class Elements | Condition Based | Interval Based | Reactive Based |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Structures (excluding bridges) | Preferred | Not Recommended | Feasible |

| Traffic Control and Management - Active Devices | Feasible | Preferred | Feasible |

| Traffic Control and Management - Passive Devices | Feasible | Feasible | Preferred |

| Drainage systems and environmental mitigation features | Feasible (except preferred for small culverts) | Preferred (except feasible for small culverts) | Feasible |

| Other Safety Features | Feasible | Feasible | Preferred |

| Roadside features | Feasible | Feasible* (not recommended for roadside hazards) | Preferred** |

| Other facilities items | |||

| Rest areas, weigh stations and buildings | Preferred | Feasible | Feasible |

| Parking Lots, Roadside litter and fleet | Feasible | Preferred | Feasible |

| Graffiti | Feasible | Feasible | Preferred |

* - Preferred for landscaping, access ramps, and bike paths

** - Feasible for landscaping, access ramps, and bike baths

Data Required for Decision-Making 2.5.4

This subsection emphasizes the significance of data collection for effective decision-making in asset management programs, particularly using a Reliability Centered Maintenance (RCM) approach. It outlines essential data requirements for different maintenance types, such as condition-based, interval-based, and reactive-based maintenance, and highlights the importance of complete and reliable data. Additionally, the document discusses desirable data that can enhance decision-making by providing clarity, supporting different agency departments, generating accurate work orders, managing asset risks, and tracking the asset's full life cycle.

Data-driven decisions depend on asset data to guide effective investment choices. Effective data collection practices allow an agency to execute strategic RCM maintenance and streamline work order distribution. With accurate data, metrics can be derived, and performance measures compared to assess the effectiveness of a maintenance strategy and identify areas for improvement. Ancillary asset data can be categorized as either essential or desirable, depending on the management approach. Regardless of the data type, it is crucial that the data be complete and reliable. Generally, the RCM process required the following essential data for effective management.

Table 2.5 – Essential Data by Maintenance Approaches for Ancillary Assets

| Maintenance Type | Asset Type | Asset Location | Asset Unique ID | Condition Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interval-based maintenance | X | X | X | - |

| Condition-based maintenance | X | X | X | X |

| Reactive-based maintenance | X | X | X | - |

There are various strategies and technologies that support data acquisition that can be found in Chapter 7 and in the Handbook for Ancillary assets (FHWA-HIF-19-006). Other desirable data can augment decision-making by:

- Providing additional clarity and accuracy to the essential data collected.

- Supporting different departments within an agency.

- Assisting in generating accurate work orders.

- Helping manage asset risks.

- Tracking the asset’s full life cycle to make informed decisions.

The above list is not all-inclusive but provides clear examples of reasons why additional data collected in the field could be beneficial to an agency. Each of these items is described in more detail in the handbook. Other desirable data attributes have been referenced elsewhere (HMEP 2013), and may also be considered, including:

- Maintenance intervals.

- Frequency of failure.

- Allocated risk factors.

- Maintenance requirements.

- Engineering specific data

Managing Ancillary Asset Data 2.5.5

This subsection underscores the importance of integrating ancillary asset data into an agency's overall data management system for informed decision-making on management, maintenance, and capital investment. It outlines guiding principles for effective data management practices, including interdepartmental coordination, an authoritative hub with integrated databases and web services, a common data dictionary, and business improvements in querying, analyzing, displaying, and reporting data.

Integrating ancillary asset data into an agency’s overall data management system ensures that decision-making associated with management, maintenance and capital investment is based on the best available information across the organization. An agency will, at the same time, improve transparency and public trust. The following guiding principles distinguish good data management practices from less comprehensive approaches to data management:

- Strategic Plan—Interdepartmental coordination.

- Authoritative Hub—Integrated database and web services.

- Common Data Dictionary—Agency agreement on assets and attributes.

- Business Improvements—Query, analyze, display, and report data.

Data management concepts are discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

Yukon Department of Highways and Public Works

The Yukon Department of Transportation and Public Works (TPW) is committed to taking a consistent, strategic approach to asset planning and management; to deliver services matching their customers’ expectations, while maximizing value for money. Vegetation management is a key part of TPW’s roadside safety program. It improves highway safety and helps preserve their infrastructure by:

- Improving visibility and vehicle sight lines.

- Reducing wildlife collisions.

- Establishing a clear zone.

- Facilitating roadside drainage.

- Preserving roadside surfaces.

- Controlling invasive weeds.

- Enhancing the overall driving experience.

The TPW roadside vegetation management program was established in the early 2000’s to address the challenges of maintaining right-of-way growth throughout Yukon. Over the past few years, the program was reassessed, leading to several improvements in the inspections and decision-making processes. This included establishing a life cycle model in the agency's dTIMS management system, to project the future condition of roadside vegetation, generate possible treatment strategies (e.g., mowing, brushing) for each section of road, and identify an optimal solution by assessing the life cycle costs and benefits from each treatment strategy for each road section. This included steps to define and compile the model inputs, including roadway inventory, vegetation condition ratings, deterioration curves, treatment options, treatment decision logic and financial parameters. The dTIMS roadside vegetation life cycle model was used to develop an optimized long-term investment plan that assessed the impacts of alternative budget scenarios and/or constraints. It also provided an example of how the software could be used by TPW staff to later model decision making for other asset types.

TAM Work Planning and Delivery 5.4.1

The approach used to deliver work can have a major impact on what investments an organization makes, the resources required to perform work, and work timing. Transportation agencies have many options for performing work, including using internal forces to perform work, and/or using a variety of different contracting approaches.

Typically, U.S. transportation agencies perform some or most of their maintenance work internally, and contract out a large portion – if not all – of their capital projects. The line between the types work performed as maintenance and capital projects varies by organization and is often blurred. Agencies can often use maintenance forces in a flexible manner to perform a wide variety of activities, including preservation activities on pavements, bridges and other assets. However, in the near term, an organization’s maintenance resources – staff and equipment, in particular – are fixed. Consequently, the asset owner is challenged to optimize use of these resources to meet immediate needs, such as winter maintenance and incident response, while performing additional work to improve asset conditions wherever possible.

The ability to contract out maintenance work, such as through Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) contracts, provides an agency with flexibility in meeting near-term needs. Other approaches for contracting out maintenance work include use of portfolio or program management contracts in which certain operations and maintenance responsibilities for some group of assets is delegated to a contractor over a specified period of time. Section 4.3.3 provides additional details on considerations involved in outsourcing asset maintenance.

Regarding contracting approaches for capital projects, in the U.S., most transportation agencies rely on Design-Bid-Build (DBB) model for delivering their capital programs. With this approach, the project owner designs a project (or contracts for a private sector firm to prepare a design) and solicits bids for project construction following completion of the design. This provides the project owner with control over the process, but can be time consuming and can result in cases where bids for project construction exceed the expected cost developed during design. In recent years, many transportation agencies in the U.S. and abroad have explored improved approaches to work planning and delivery to accelerate completion of needed work, leverage alternative financing approaches and transfer program and project risk.

All of these approaches are intended to reduce the time from initial conception of a project to its completion, and in many cases transfer risks associated with project completion from the public sector to the private sector. As these examples help illustrate, major trends in this area include:

- Group work together by geographic location or type of work to develop fewer, larger, and more easily contracted projects

- Use Design-Build (DB), Design-Build-Finance-Operate-Maintain (DBFOM) and other contracting strategies, wherein a single contract is awarded to design and complete a project, as opposed to separate contracts for design and construction

- Encourage development of Alternative Technical Concepts (ATCs), wherein a contractor proposes an alternative approach to meeting a contract requirement in the bidding phase

- Select contractors earlier in program/project development through use of Construction Manager-General Contractor (CM-GC) arrangements, where a contractor is selected as Construction Manager while design is still underway

- Use IDIQ contracts and other flexible contracts to provide a more efficient mechanism for performing smaller projects

- Incorporate performance-based specifications, time-based incentives and other specifications in contracts to improve project outcomes

- Outsource operations and maintenance of an asset using program or portfolio management contracts.

Both in the U.S. and abroad there are many examples of public agencies making extensive use of alternative contracting strategies, such as Public-Private Partnerships (P3s) and performance-based contracts to speed project delivery and transfer risk.

While alternate strategies for work planning and delivery hold great promise, all of the approaches described here have advantages and disadvantages and carry their own risks. Use of alternative approaches can save taxpayers money and provide improvements more quickly than a traditional model. Success stories typically result from improving the efficiency of the process and incentivizing the use of better technology and methods, but there are also many cautionary examples in which these strategies have failed to achieve cost savings, time savings or risk transfers as desired. Asset owners should consult the separate body of research in this area (referenced at the end of this section) when exploring the use of alternative approaches and carefully weigh the expected return, advantages and disadvantages of whatever delivery approaches they consider.

Types of Performance-Based Data to Monitor 6.2.1

This section describes the types of information that should be collected and maintained to support performance-based decisions for physical assets. This section focuses on asset inventory and condition information for life cycle management, but recognizes that other operational performance characteristics may be important to determine whether an asset is fulfilling its intended function.

Differences in Performance and Condition

The terms ‘performance’ and ‘condition’ are often used interchangeably, although they have different meanings in a performance-based environment. The performance of an asset relates to its ‘ability to provide the required level of service to customers3’ while condition is generally considered to mean the observed physical state of an asset, whether or not it impacts its performance. For example, a bridge with scour may continue to perform adequately in the short-term even though it may receive a low National Bridge Inventory (NBI) rating because of the deterioration.

Inventory Information

An asset inventory provides information other than performance data important for estimating the amount of work needed, identifying the location of work in the field and determining characteristics capable of influencing the type of work to be performed. The RCM approach introduced in Chapter 4 can be used to help an agency determine what information is needed to support the management of each type of asset. The asset inventory requirements for those assets managed based on a specified interval for repair, such as pavement markings, is very different than those required for an asset managed using a condition-based approach, such as pavements or bridges. Regardless of how detailed the asset inventory is, it is important an agency establish processes to ensure data quality and keep the inventory current over time.

There are several basic data attributes essential to effectively managing transportation assets, including asset type, quantity and location. Additional information that is important is to differentiate between the types of work to be performed, which may also be added to the inventory, the type of material used to construct the asset, the last time work was performed and factors influencing the use of the asset (e.g. traffic levels, highway functional classification or climatic conditions).

As discussed in Chapter 7, managing asset inventory information using an integrated approach to data management helps promote consistency in asset data across an agency and provides access to help ensure the data is used by decision makers at all levels of the organization. An out-of-date inventory makes it difficult for an agency to estimate work quantities accurately for budgeting purposes.

Condition Information

Asset condition information is used to determine how assets are performing and how performance changes over time. The lack of condition information may lead to premature or unexpected failures with the potential to be very costly, negatively impacting system performance and increasing agency risks. Methods of collecting asset condition information are discussed further in Chapter 7. To ensure that condition information remains current, it is important that the information is updated on a regular basis.

Asset Condition

There are several approaches for assessing asset conditions, each of which is influenced by the type of asset and the resources available to support the process. Typically, an assessment of asset condition involves a method of evaluating the presence of deficiencies and/or deterioration at the time of inspection. The results are used to assign a rating or LOS used to determine the need for maintenance, rehabilitation or replacement now or in the future. Asset condition ratings may also be used to establish rates of deterioration, allowing an agency to forecast future conditions for planning purposes.

Examples of commonly used types of asset condition ratings are listed below.

- A pavement condition index based on the type, amount and severity of distress present, which could be on a 0 to 100 scale, with 100 representing an excellent pavement.

- The National Bridge Inventory (NBI), which assigns a rating between 1 and 9 based on the deterioration present in each element (deck, superstructure, substructure and culvert).

- A LOS rating of A to F for maintenance assets, such as the percent blockage in a culvert or the percent of guardrail not functioning as intended.

Maintaining asset condition information is important for evaluating performance to determine whether improvements are needed to achieve the agency’s strategic objectives. The lack of current condition information, or a lack of confidence in the condition information, makes it difficult to present investment needs to stakeholders with any degree of confidence.

Asset Performance

The results of condition surveys or inspections are used to evaluate the performance of each asset in terms generally understood by stakeholders, such as Good, Fair or Poor.

It is common for transportation agencies to report the percent of the network in Good or Fair condition or the percent of drivers traveling on roads in Good and Fair condition. Asset performance can also be reported in terms of a health index, such as the Remaining Service Life (RSL) used by some state DOTs to indicate the amount of serviceable life left in the asset. In the maintenance community, some state DOTs have developed a Maintenance Health Index or overall LOS grade to represent the performance of the entire Maintenance Division rather than report the grades of each category of assets separately.

Asset performance also influences overall system performance, as demonstrated by the impact on system reliability associated with unplanned road or bridge closures due to flooding or an on-going lack of maintenance. Performance data related to delay, unplanned closure frequency, GHG emissions, and crash locations may all be impacted by asset conditions and affect an agency’s ability to achieve its broader, strategic performance objectives such as system reliability, congestion reduction, environmental sustainability, and freight and economic vitality. For example, it is important to monitor performance characteristics such as travel time reliability to determine whether capital improvements are needed to add additional lanes or whether ITS assets could improve traffic flow during peak periods.

Ohio DOT

The Ohio DOT recognizes the importance of integrated management systems to support both life cycle and comprehensive work planning activities. One of the tools developed by the Ohio DOT is its Transportation Information Mapping System (TIMS), which enables planners, engineers and executives to access and manage key asset, safety and operational data in an integrated web-mapping portal (https://gis.dot.state.oh.us/tims). The portal is available to both internal and external stakeholders and allows users to access information about the transportation system, create maps or share information. The data integration efforts enabling TIMS are now underpinning all management system implementations.

Maintaining Asset Data 6.2.2

This section describes several approaches to keeping asset inventory and condition information current, so it can be used reliably to track accomplishments and evaluate current and future needs. The methodologies used to collect the asset information is discussed in Chapter 7.

Maintaining Inventory Information

One of the challenges transportation agencies face is keeping their asset inventory current, because it can require business processes dependent on individuals or agency work areas that differ from the primary asset owners. For example, construction may be responsible for installing new guardrails as part of a pavement-resurfacing project, but the information is not always made available to the maintenance division responsible for budgeting and scheduling guardrail repairs.

Establishing Processes to Update Inventory Information

Some types of inventory information change regularly while other information changes infrequently. As a result, it is important to classify each type of data and establish procedures in order to ensure the inventory is updated as information changes. An agency should establish business processes to ensure any changes to the inventory are reflected in relevant databases. For example, each time a pavement improvement project is completed, the database should be updated with information about the new surface type, the project completion data and the other assets replaced as part of the project. Establishing these processes and holding individuals responsible for updating this information are important for the ongoing success of a performance-based management approach.

Maintaining Condition Information

Asset condition and performance information must also be updated on a regular cycle. In some cases, data collection cycles are mandated by regulations, such as federal requirements for reporting pavement and bridge condition information on the National Highway System. Where there are no requirements in place for condition reporting, the update frequency should be determined based on the resources available, how the asset is managed and the data analysis cycle. Different update frequencies may be established for different types of assets.

Asset condition information may be collected based on a regular interval schedule or an inspection may be triggered based on the asset’s condition. For example, an asset in poor condition may require inspection more frequently than an asset in good condition. In general, asset information is updated on a 2- to 4-year cycle, but in some cases asset data is collected more frequently. For instance, some agencies collect performance data on maintenance assets several times a year to ensure they are in good working order and performing as expected. The condition of other assets with a slower rate of deterioration may be conducted less frequently.

Virginia DOT

The Virginia DOT maintains most of the assets on state roads and regularly assesses the condition of those assets for determining investment needs. For pavements and bridges, there are asset leads at both the central office and in the districts to monitor conditions and update the database based on work completed. Asset leads at the central office manage statewide data monitoring and analysis and provide guidance on the work that is needed. The asset leads in the districts are responsible for implementing the work and recording completed work in the bridge and pavement management systems so the information is always current.

TAM Data and Systems 7.1.1

Often organizations maintain data on inventory, condition and needs for individual asset classes in separate, self-contained systems. However, increasingly it is necessary to integrate asset and related data distributed across multiple systems to support decision-making.

As discussed in Chapter 6, there are several different types of information needed for TAM decision making. These include:

- Asset inventory and design information including location, type, quantity, material, and design details. This also includes summary level information about the asset as a whole as well as information about individual asset components (e.g. different pavement layers or bridge elements). It may also include asset valuation information (calculated based on deteriorated replacement cost, historic cost, or fair market value).

- Asset condition and performance information including results of visual inspections, measured condition (such as roughness or cracking for pavements), and computed measures of performance (such as remaining service life or “deficient” status designation). This also includes aggregated network level measures (such as the percentage of pavement in good condition).

- Contextual information such as system or network characteristics, functional classification, highway geometric characteristics, traffic volumes, congestion and reliability, crash history, adjacent land uses, weather and features of the natural environment. This information is helpful for understanding factors that may impact the asset service requirements or goals, physical deterioration, funding eligibility, and/or project needs and constraints.

- Work information including date, cost and scopes of work proposed, scheduled and completed on assets – including installation, replacement/reconstruction, rehabilitation, preservation and maintenance. When projects include multiple assets, it is valuable to itemize the work performed by asset.

- Revenue and funding allocation information including historical and forecasted funds available for asset installation, replacement/reconstruction, rehabilitation, preservation and maintenance – by source; and historical allocations by asset category and work type.

- Analysis information including forecasted condition and needs under varying funding or program scenarios, treatment life or life extension results, or project prioritization ratings or rankings.

Agencies store and manage TAM-related data within several different information systems:

- Asset Management Systems (AMS) – this includes pavement management systems (PMS), bridge management systems (BMS), management systems for other specific asset classes (sign or signal management systems), and systems used to manage information for multiple asset classes. All of these systems are used to store inventory and inspection data, and track work performed on an inventory of assets. They also typically include contextual information needed for modeling and analysis, such as traffic, functional classification, number of lanes, and presence of a median. More advanced management systems may identify and forecast preservation and rehabilitation or replacement needs, and analyze funding scenarios. However, often agencies use multiple systems for this purpose, with separate systems for maintaining the asset inventory and predicting future conditions. Pavement and bridge management systems are typically used as the sources for federal Highway Performance Monitoring System (HPMS) and National Bridge Inventory (NBI) reporting.

- Maintenance Management Systems (MMS) – used to plan and track routine maintenance activities. These systems typically store information about planned and completed maintenance activities and resources (labor, materials, equipment) consumed. MMS may include customer work requests, work orders, and maintenance level of service (LOS) information. Some MMS do not store any asset inventory data. In such cases, work is tracked by maintenance activity category and route section rather than specific asset. Note that there are many commercial Asset Management Systems that provide full functionality for asset inventory, inspection/condition assessment, work planning, and work tracking.

- Program and Project Management Systems (PPMS) – used to manage information about capital and major maintenance projects from initial planning and programming through completion. There may be separate systems for managing programming/funding information, preconstruction/design information and construction phase information. Some agencies integrate data from these various systems to obtain a single source of project information. Project information typically includes a mix of tabular data as well as unstructured data (for example, documents and images). Unstructured data may be managed within an engineering content management system separately from other data.

- Financial Management Systems (FMS) – used to manage and track revenues, expenditures, budgets, grants, payments, receipts, and other financial information. These systems are often supplemented with special purpose tools supporting budgeting, revenue forecasting and analysis.

- Enterprise Resource Planning Systems (ERP) – incorporate features of financial systems as well as a wide variety of other modules for functions including human resources, payroll, purchasing, maintenance management, inventory management, equipment management, project programming, project financial management, and revenue forecasting.

- Highway Inventory Systems (HIS) – used to store and report administrative and physical characteristics of the roads and highways. Federal Highway Performance Monitoring System (HPMS) requirements and the Model Minimum Inventory of Roadway Elements (MIRE) define standard road inventory elements; some DOTs maintain additional elements. HPMS elements include pavement type, pavement condition (roughness, cracking, rutting and faulting), and structure type. These systems may include Linear Referencing System (LRS) management capabilities or, may be integrated with a separate LRS management system. Per FHWA’s All Roads Network of Linear Referenced Data (ARNOLD) requirements, state DOTs must submit an LRS for all public roads to FHWA, linked to their HPMS data.

- Crash Data Systems (CDS) – used to store and report data about collisions and resulting injuries and fatalities; which when combined with traffic data and road inventory data provides information for identifying traffic and safety asset needs.

- Traffic Monitoring Systems (TMS) – used to store and report traffic data, required for federal reporting and used for a wide variety of purposes, including TAM processes for asset deterioration modeling, treatment selection and prioritization.

- Engineering Design Systems (EDS) – used to create design drawings or models including design details for different assets. As agencies adopt 3D object-based design modeling practices, there are opportunities to share information about assets between design models and other asset data systems used across the life cycle.

- Enterprise Geographic Information Systems (GIS) – used to manage spatial information, including asset location. Assets may be represented as point, linear or polygon features; location may be specified based on coordinates and/or based on a linear referencing system (LRS). Asset features maintained within GIS may be linked to asset information within other systems.

- Imagery Databases (ID) – used to store highway video imagery and mobile LiDAR data that can be used for manual or semi-automated extraction of asset inventory.

- Data Warehouses/Business Intelligence Systems (DW/BI) – used to integrate data from source systems for reporting and analysis. These may be tailored for TAM decision support.

- Other – there may be other specialized decision support tools that produce analysis results – for example, tools for life cycle cost analysis, cross-asset optimization, or project prioritization.

TIP

Taking stock of what data and information systems supporting TAM is a critical first step to take before pursuing data integration and system development initiatives.

Table 7.1 provides an overview of different systems with the types of information they typically contain. Note that this may vary within each agency.

Table 7.1 - TAM Data and Systems Overview

| Asset Inventory, Condition, and Performance | Contextual | Asset Work Information | Revenue and Funding Allocations | Analysis Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asset Management Systems | • | • | • | • | • |

| Maintenance Management Systems | • | • | • | • |

|

| Program and Project Management Systems | • | • | • |

||

| Financial Management/ERP | • | • | • | ||

| Road Inventory Systems/HPMS | • | • | • | • | |

| Crash Databases | • | ||||

| Traffic Monitoring Systems | • | ||||

| Engineering Design Systems | • | ||||

| Enterprise GIS Databases | • | • | • | • | |

| Imagery Databases | • | ||||

| Data Warehouses/BI | • | • | • | • | • |

| Other | • |

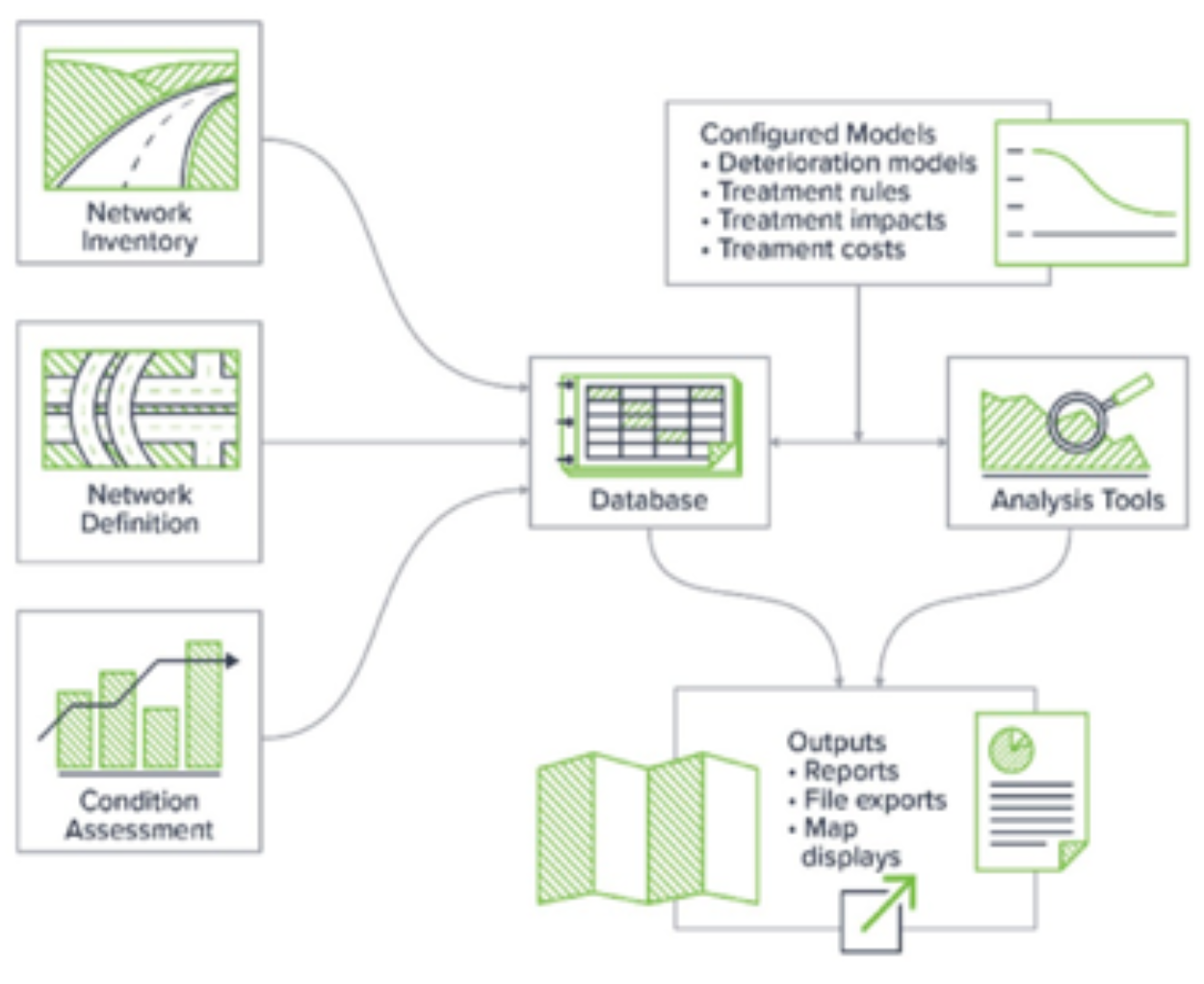

Common components included in computer-based asset management information systems are shown in Figure 7.1. Network inventory, network definition (e.g., location), and asset condition information serve as the primary components in a database, which may or may not be external to the management system. Agency-configured models are used to predict changes in asset condition over time and to determine what treatments are appropriate as the assets age and deteriorate. These models may be developed and updated based on historical condition and cost data.

When developing a computer-based model, an objective (performance, condition, financial, risk) must be defined within the model for it to evaluate these criteria to develop and select optimal strategies. Metrics such as benefit-cost, risk, condition and treatment costs are often used.

A typical pavement management system performs some type of benefit/cost analysis that determines the performance benefits (typically in terms of improved condition) and the costs associated with each possible treatment timing application. By selecting the projects and treatments with the highest benefit/cost ratio, an agency can demonstrate that it is maximizing the return on its investment.

Bridge management systems more typically rely on optimization to perform a single-objective analysis, such as minimizing life cycle costs or maximizing condition, or a multi-objective optimization analysis that considers factors such as condition, life cycle cost, risk of failure, and mobility. Project- and/or network-level benefit/cost analyses are used in a bridge management system to explore all feasible treatment options over an analysis to determine the most cost-effective set of treatments with the highest benefits to the network.

TIP

Start by defining what questions the agency wants to answer and then make a plan for how data across systems could be integrated to answer these questions.

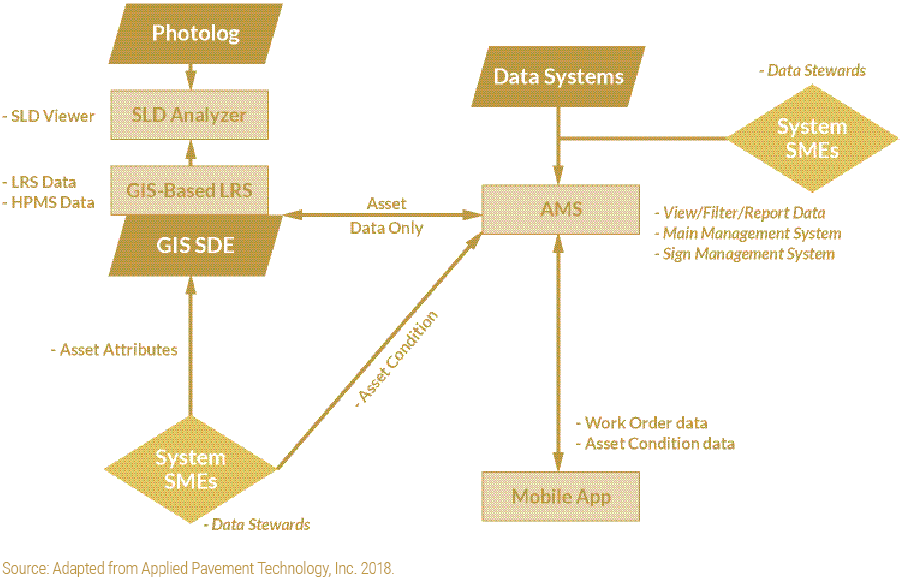

Figure 7.2 shows an example of how the different systems listed in Table 7.1 might be integrated, adapted from the approach used by a U.S. state DOT.

Why Integrate? 7.1.2

Integrated views of asset information enable insights that lead to better decisions. Information produced by one part of the agency can support decision making across the agency.

Linking information across different systems enables agencies to quickly answer important questions that might have taken hours of staff time without integrated data. Integrating data opens up access to previously siloed data sets across the organization. It allows an agency to reduce duplicative effort, achieve efficiencies and derive greater value from its data. Some questions that rely on integrated data are:

Investments and Accomplishments

- What have we spent over the past ten years on route X in county Y (across all assets and including both maintenance and rehabilitation)?

- What percentage of deficient pavements will be addressed by our current capital and major maintenance programs?

Work Costing and Scoping

- What does it cost us to restripe a mile of pavement markings in each district?

- What locations identified along the linear referencing system (LRS) are planned for next year?

- Do the costs estimated by our pavement management system match what we are actually seeing in our projects?

- If we upgrade our guardrails whenever we do a paving project, how long will it take, and what will it cost to eliminate the current backlog?

- How can we best plan our projects to address multiple needs that may exist along a corridor?

Performance

- How many years does our standard mill and fill pavement treatment last for roads in different traffic volume categories?

Tradeoffs and Prioritization

- How should we prioritize our asset replacement/rehabilitation projects, considering not only life cycle management strategies but also stormwater management, safety, congestion, non-motorized, transit and ADA needs?

- How should we allocate our available funds across multiple asset types?

Disaster Recovery

- What assets were on route X in county Y prior to the storm? What will it cost to replace them?

An integrated approach to asset data collection, management and reporting not only makes it easier to answer these questions; it also can reduce costs. Opportunities for achieving efficiencies include:

- Using a single application to manage information about multiple assets.

- Using Data Warehouse/BI and GIS tools to provide reporting and mapping functions rather than investing effort to develop these capabilities within individual asset management systems.

- Gathering data on multiple assets through the same approach – using mobile technology, video imagery and/or LiDAR (see section 7.2)

- Sharing asset data across the life cycle – for example, automating methods for extracting asset data from design plans to update asset inventories (described further below).

Emerging technologies and new data sources are making an integrated approach to asset data management even more important. For instance, there are increasingly opportunities to use data collected from cell phones and connected vehicles that may cut across many asset categories. Also, there has been and will likely continue to be rapid advancement in machine learning techniques, such as for extracting asset data from video imagery or predicting optimal maintenance interventions given a wide array of data. Using these techniques typically requires establishing large, integrated data sets.

In addition, advances in computer-aided design and engineering software are making it possible to integrate asset data across the life cycle and achieve efficiencies and cost savings in maintaining asset inventories. See the discussion in section 7.1.4 further on.

TIP

Integrating information systems can be approached incrementally. Have a long term goal in mind and find opportunities to move towards this goal as systems are upgraded or replaced.

Ohio DOT

Ohio DOT has separate pavement and structures management systems, but integrates both asset and project information within its Transportation Information Management System (TIMS). A separate Transportation Asset Management Decision Support Tool (TAM-DST) allows for a user to combine data from TIMS with other state-maintained data sets to perform analysis and reporting. The application allows for one to consume large quantities of data in a timely manner to help make better choices in planning. See practice examples in Section 2.2.4 and Section 6.2.1 for more information on TIMS.

Planning for TAM Information Integration 7.1.3

There are different levels of integration. In the short term, agencies can integrate the information they already have. In the longer term, agencies can modify and consolidate their information systems. Integrating data for TAM should be approached systematically to ensure agencies achieve a solution that meets their needs and is ultimately sustainable.

Step 1: Establish Requirements

What is the purpose of the integration? To create a publicly available map showing asset conditions and projects for both internal and public use? To create a BI environment for answering a range of questions about asset performance and cost? To integrate asset data across different systems used for planning, design, construction, and maintenance?

Based on the identified needs, determine what data will be integrated and at what frequency. Consider whether this will require historical data, current data, future projections, or a combination.

Early collaboration between business units and information technology units is important to establish a shared understanding of both business needs as well as technical requirements and constraints. A strong business-IT partnership is essential for successful information integration initiatives.

Step 2: Identify and Evaluate Data Sources

Identify the available data sources to meet requirements. Determine where the data reside, and in what form – such as engineering design systems, relational databases, spreadsheets, document repositories, etc. Assess the current level of data quality to make sure that the source is ready for integration, based on discussions with the data steward or through examining the data. For design files/models a key quality consideration is whether established standards have been consistently applied. It is also important to determine the level of spatial and temporal granularity – or what does each record represent (such as a pavement condition observation for a 0.1 mile section for April 2019; a paving project on a 1.5 mile section due to open for traffic sometime in 2020).

Step 3: Analyze Linkages

Identify how different data sources will be linked. Spatial linkages are a good place to begin. If GPS coordinates are used, make sure that the Coordinate Reference System (CRS) used is documented, along with positional accuracy. If a Linear Reference was used, determine what method was used to establish the measure along the route, and what version of the agency’s LRS was used to establish route identifiers and reference points. Find out if the linear reference has been updated to reflect changes in the LRS since the data were last collected (if applicable).

TIP

Set standards for how assets and work activities will be linked to GIS/LRS locations. Then create processes and tools to make sure these standards are followed.

Identify other types of (non-spatial) linkages that may be needed to join different data sources – for example, project numbers, account codes, work order numbers, etc. Agencies may want to profile the data for these elements to understand variations in coding and formats.

Step 4: Design Data Flows and Select Technology Solutions

Based on the requirements, available data, the linkage analysis and the tools and resources available within the agency, design how the data will flow from sources to target systems, and select the technology solutions to be used for performing the integration itself. The target system might be a general purpose enterprise geodatabase, an enterprise asset management database, a BI tool reporting data source, data warehouse, or a data lake. Data Extract-Transform-Load tools are available from data warehouse vendors; simple integration tasks may be accomplished through scripting. There are also a variety of specialized tools available for transforming and combining spatial data, and for extracting data from CAD/3D models.

Step 5: Design and Implement Integration Methods

Develop the technical approach for transforming link fields so that they are consistent across databases and if applicable, joining the different data sets and combining common data elements from the different sources. This may involve spatial processing (such as dynamic segmentation), aggregation, coding conversions, and other transformations.

Short term integration strategies include:

- Creating GIS data layers and making them accessible in available web and desktop-based GIS software. This strategy requires that each data source uses compatible spatial referencing, or can be converted to a common referencing system.

- Creating a database or view combining data from various source systems, and using available BI/Reporting tools to create reports and data visualizations. This strategy requires identifying common “dimensions” across source systems and/or normalizing data so that it can be summarized. For example, if the agency wants to report asset quantities by district or county by year, it will be necessary to make sure that each source has these data elements and that the data can be converted to a consistent set of values.

- Exposing data from authoritative sources as services via Application Programming Interfaces (APIs).

In the longer term, agencies can consider re-architecting or consolidating their systems so that they work better together. A logical way to approach this is to document the “as is” situation and then map out a “to be” architecture. This will allow the agency to chart a path from the current state to the desired future state. It will also provide a framework for capturing requirements for any new systems that are brought into the agency.

Integrated asset management systems are not a new concept and there are several commercial systems that support information management and work planning for multiple asset types. However, some agencies are challenged to integrate information about major assets (pavements and bridges) with information about various other ancillary assets – given that approaches to planning and budgeting for major assets are more sophisticated and require a greater level of detailed information and analysis. Also, it can be a challenge to integrate information about operations and maintenance with capital projects given differences in how work is categorized, performed, and tracked.

TIP

Find opportunities to save on data collection costs by capturing asset information during project design and construction.

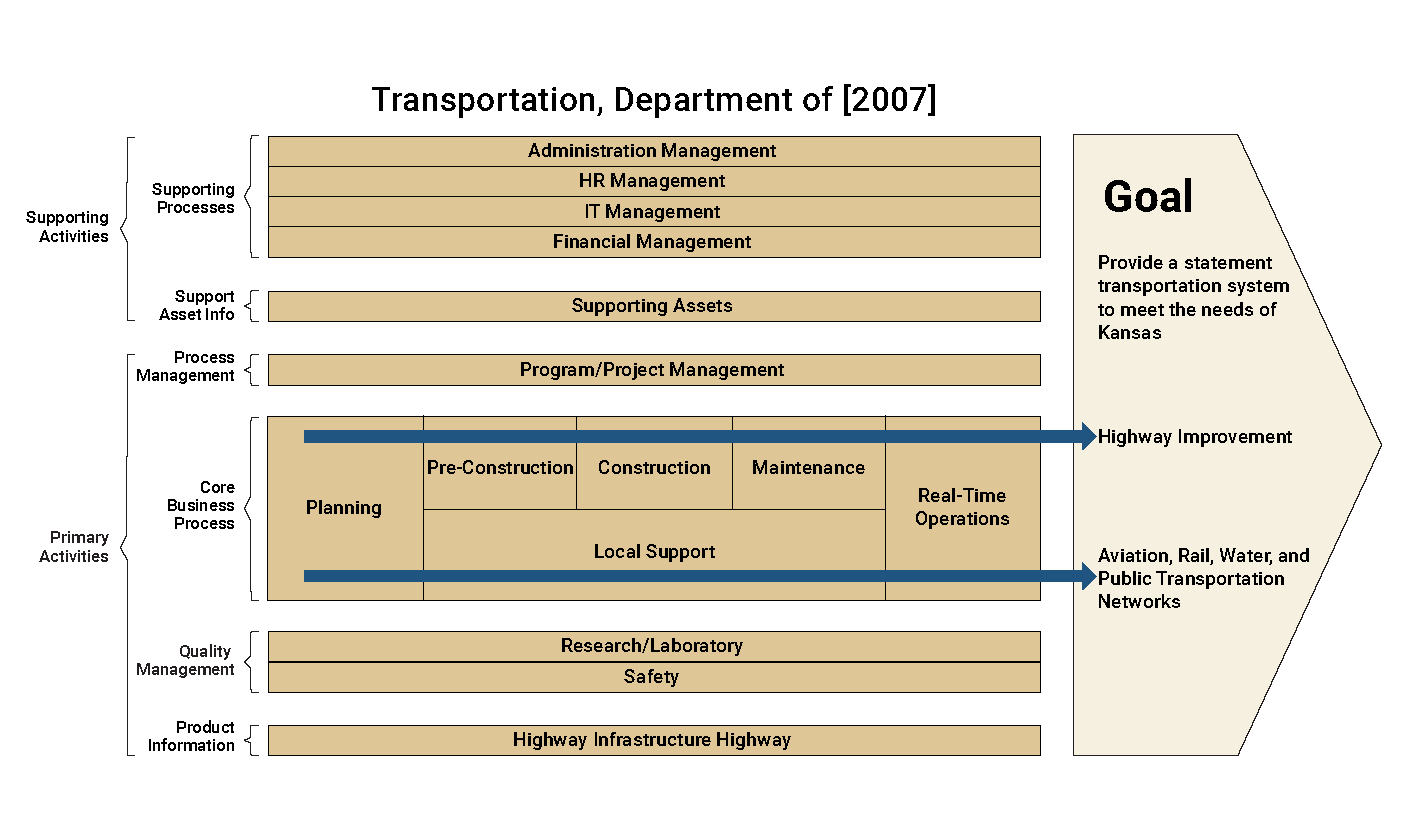

Kansas DOT

KDOT’s architecture was based on a value chain model that represents the agency’s business components and relationships. It included a set of “context diagrams” showing information flow across systems and actors for major subject areas including highway asset systems, long range planning, pre-construction, construction and maintenance. While an architecture does require significant effort to create and maintain, it provides a more global and stable view of business processes and information needs than what would be produced through a piecemeal, incremental approach to system upgrades and replacements. This view can be used to plan the path from the existing set of systems to a more efficient and integrated set.

Source: Adapted from Kansas Department of Transportation. 2003. Enterprise IT Architecture

Integrating Asset Information Across the Life Cycle 7.1.4

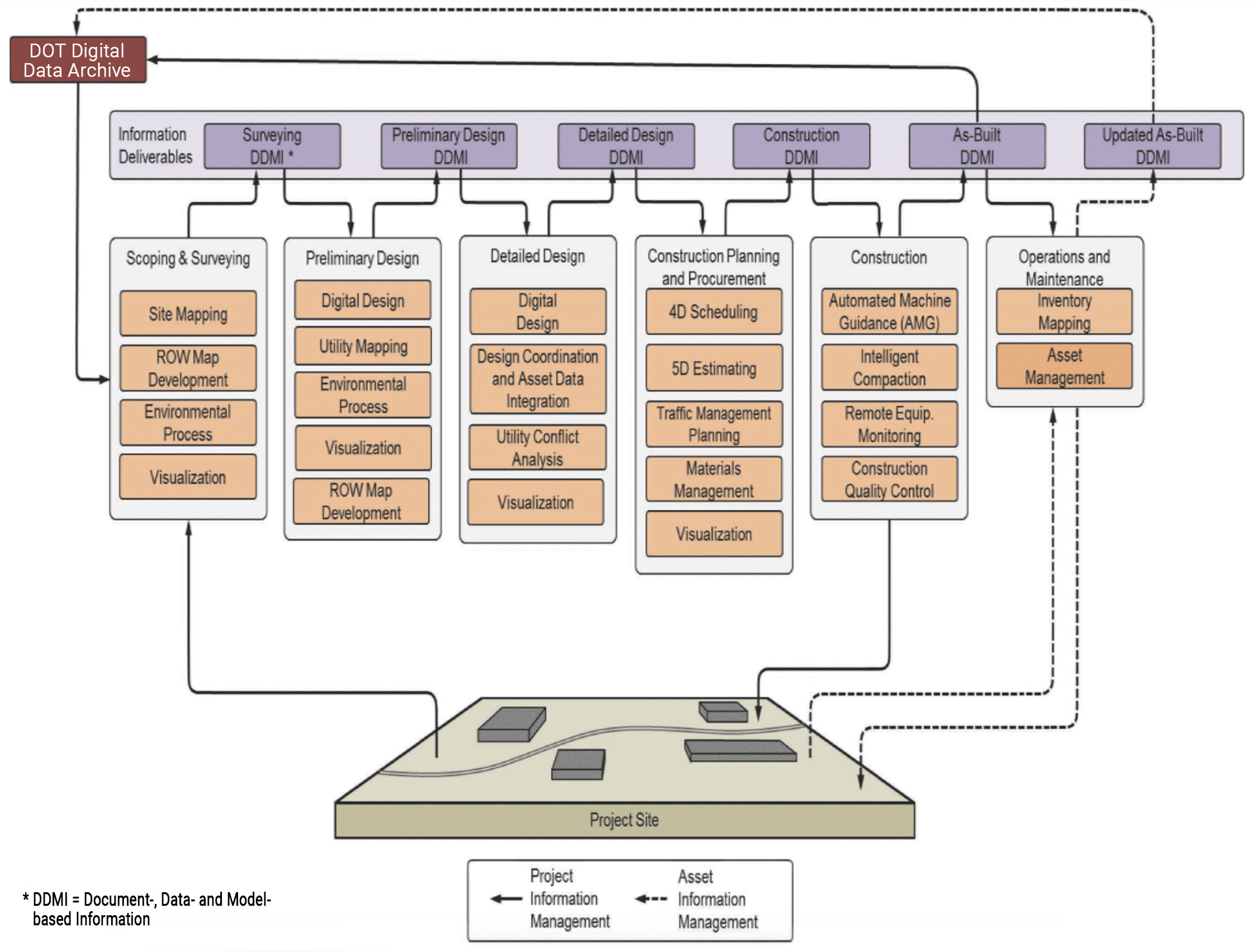

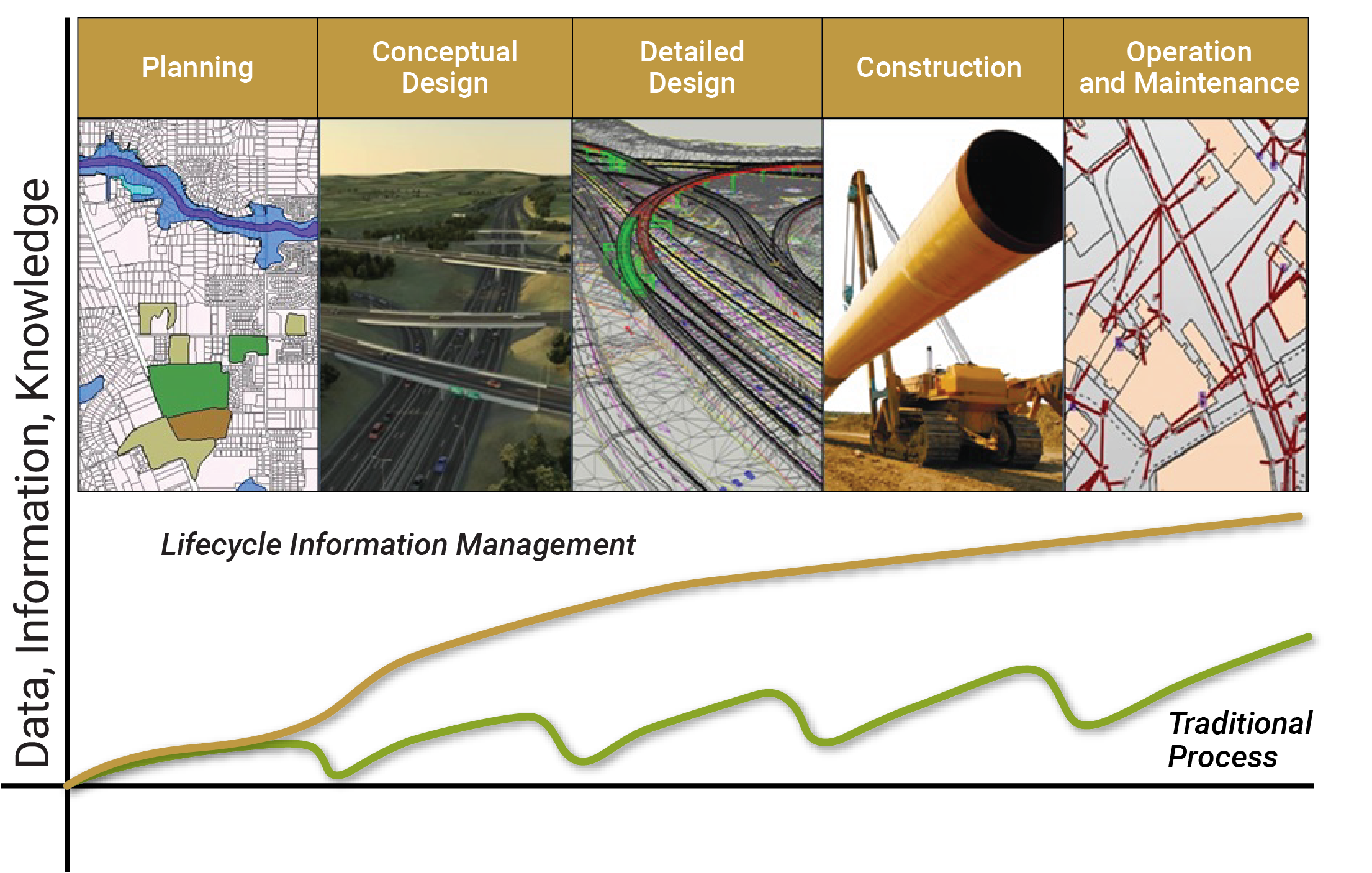

As assets are designed, created, maintained, restored, and replaced, different systems are typically used to keep records of asset characteristics, conditions and work. Ideally, information created at one stage of the asset life cycle is made available for use at the next stage. Techniques, tools and processes are available to manage data for an asset over its entire life cycle from construction or acquisition to disposal.

Integrating information across the transportation infrastructure life cycle is an area of significant interest in the transportation industry. Several terms have been used to describe the collection of processes, standards and technologies for accomplishing such integration – including Civil Integrated Management (CIM) and Building Information Modeling (BIM) for Infrastructure. In 2019 ISO issued its first BIM standard, ISO Standard 19650. This builds on an earlier standard published by the British Standards Institute (BSI).

Traditionally, information created at one phase of the life cycle is archived and not made available to downstream processes. There are substantial opportunities for cost savings by using a shared, electronic model of the infrastructure, defining information needs at each life cycle phase, and establishing procedures for information handoffs across the life cycle. For example, information about assets included in a construction project can be compiled during design and linked to the model representations of the assets. This information can be confirmed and corrected during construction and made available to asset management systems when the project is completed and turned over to maintenance and operation.

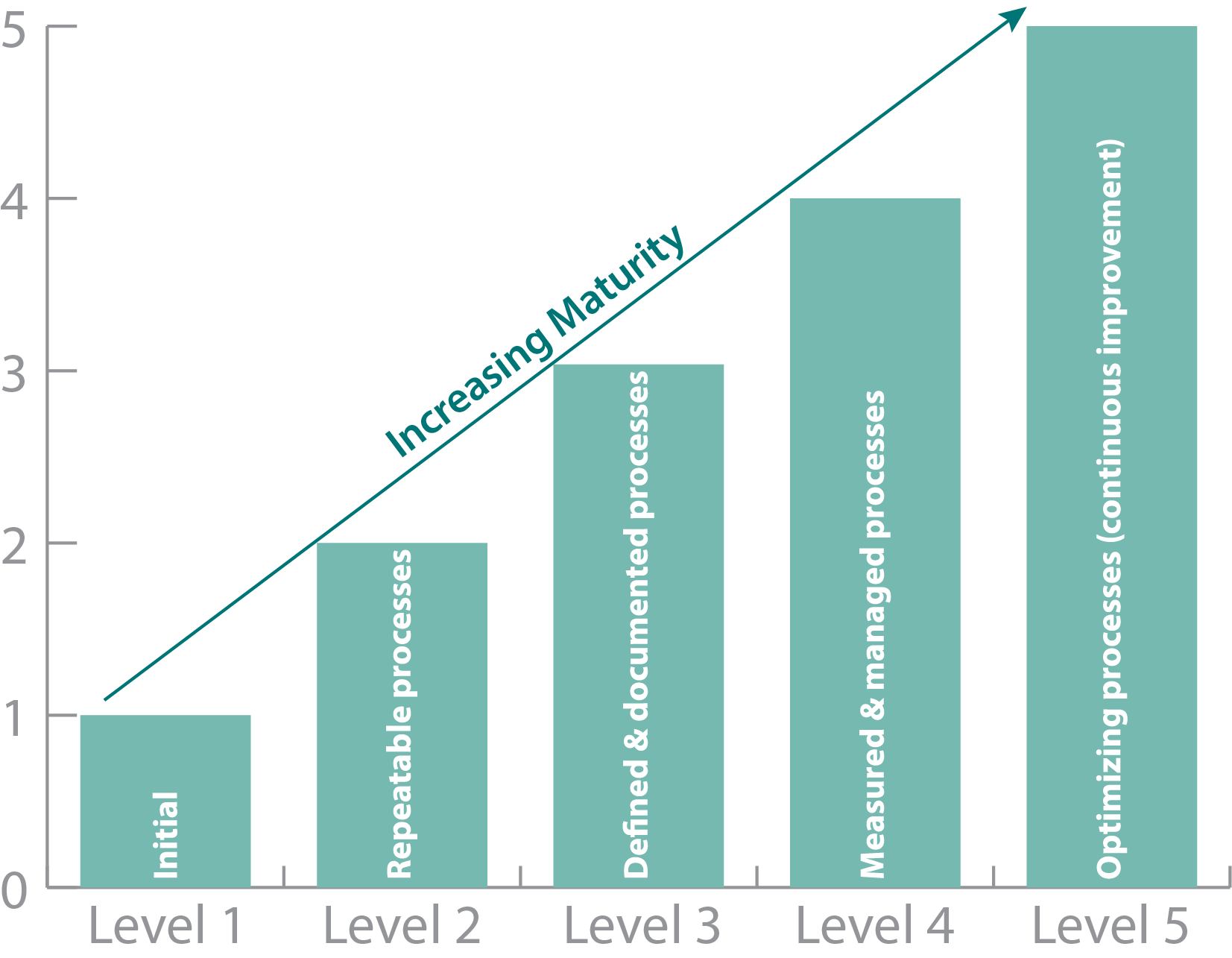

Such integration can reduce duplicative data collection efforts, and speed the time required to make decisions and perform work. Implementing these techniques requires much more than adoption of technology supporting 2D and 3D models. A commitment to common standards and processes is needed. Recognizing that this scale of change takes time, maturity models and levels of implementation have been defined to guide agencies in developing roadmaps for enhancing life cycle information integration over time. See the references at the end of this chapter for further information.

Figure 7.3 Integrated Workflow Model for Sharing Information Across the Life Cycle Components

Transportation Research Board. 2016. Civil Integrated Management (CIM) for Departments of Transportation, Volume 1: Guidebook. https://www.nap.edu/read/23697/chapter/5#16

CrossRail & Transportation for London

Crossrail is a major design-build project to construct a new railway line across central London (UK). It includes 42km of track and 10 new underground stations. Project construction began in 2009. The project is being delivered by Crossrail Limited (CRL), currently a wholly owned subsidiary of Transport for London (TfL). Once the project is complete it will be operated by TfL as the Elizabeth Line. The Crossrail project provides a good example of the application of several BIM elements. Early on, CRL established the following objective:

To set a world-class standard in creating and managing data for constructing, operating and maintaining railways by:

- Exploiting the use of BIM by Crossrail, contractors and suppliers

- Adoption of Crossrail information into future infrastructure management (IM) and operator systems

CRL established a Common Data Environment (CDE) with integrated information about the project and the assets it includes. This environment included CAD models, separate linked databases containing asset details, GIS data, and specialized applications for scheduling, risk management and cost management. Data warehousing techniques were used to combine and display integrated information. Considerable work went into defining asset data requirements and setting up standard, well documented data structures and workflows to provide an orderly flow of information from design through construction, and on to maintenance and operation. It was essential to create a common information architecture given that work on each of Crossrail’s nine stations was conducted by different teams, each consisting of multiple contractors. Each station was comprised of over 15,000 individual assets.

Key elements of the approach included:

- A common asset information database with standard templates for deliverables. This database serves as the “master data source from which playlists of information can be created.”

- An asset breakdown structure (ABS) that relates facilities (e.g. stations) to functional units (e.g. retaining walls) to individual assets (e.g. steel piles).

- Asset naming, identification and labeling standards that distinguish functional duty requirements (e.g. a pump is needed here) from specific equipment in place fulfilling these requirements.

- Asset data dictionary definition documents (AD4s) that lay out the specific attributes to be associated with different types of assets, based on the ABS.

- Sourcing of the asset data from design and as-built information.

- A Project Information Handover Procedure specifying the methods of data and information handover for maintenance and operations once the construction has been completed.

- Use of a common projected coordinate system for CAD and GIS data

- Use of a federated data model in which information was maintained within separate special purpose systems, with a common master data model enabling sharing and interpretation of data from the different sources. The master model included elements such as time periods, budget and schedule versions, organizations, data owners, contractors, milestones and key events.

Sources:

https://learninglegacy.crossrail.co.uk/documents/building-a-spatial-infrastructure-for-crossrail/

BIM Lifecycle Information Management

Source: Adapted from Crossrail. 2016. Building A Spatial Data Infrastructure For Crossrail. https://learninglegacy.crossrail.co.uk/documents/building-a-spatial-infrastructure-for-crossrail/

TAM Data Guide 7.1.5

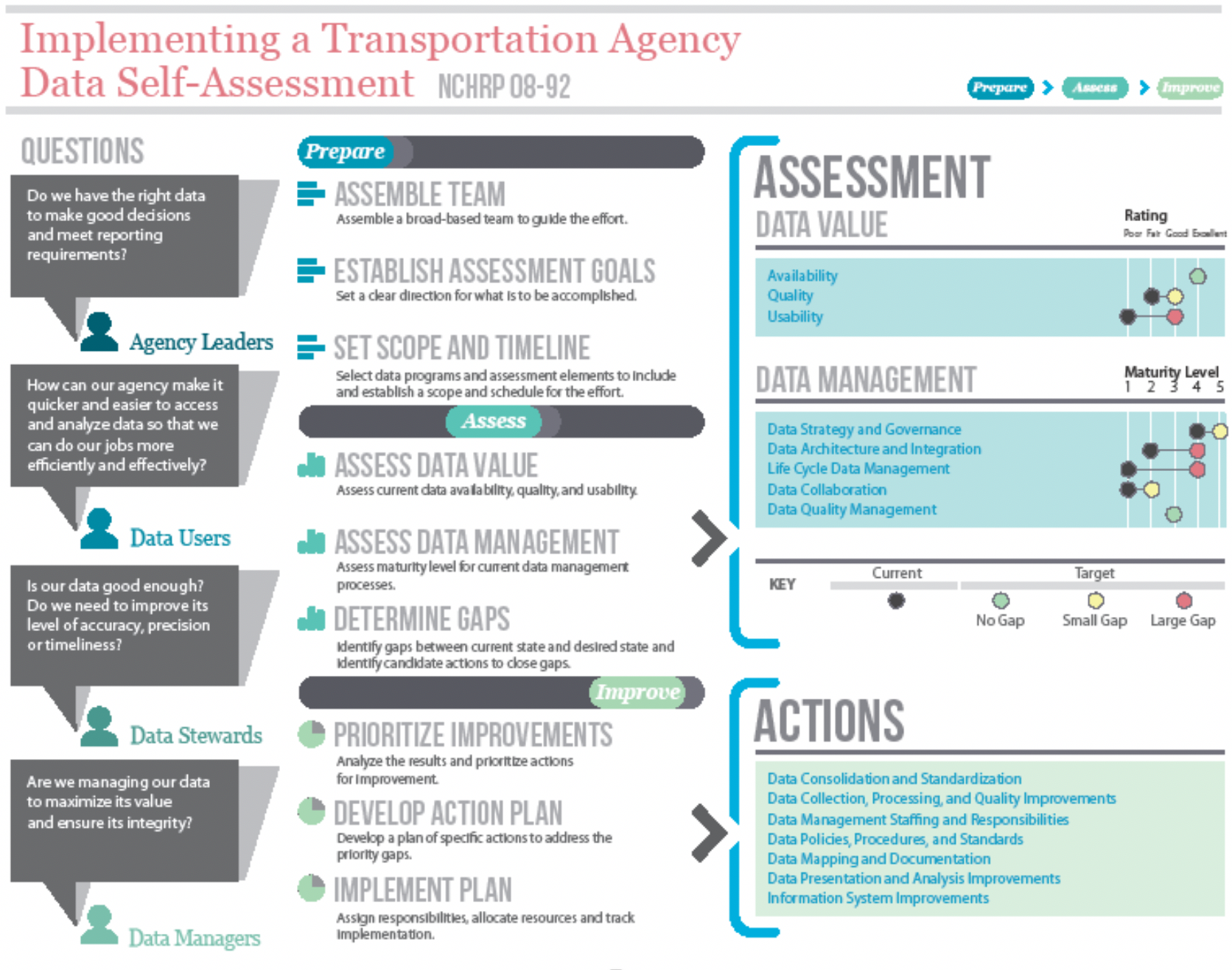

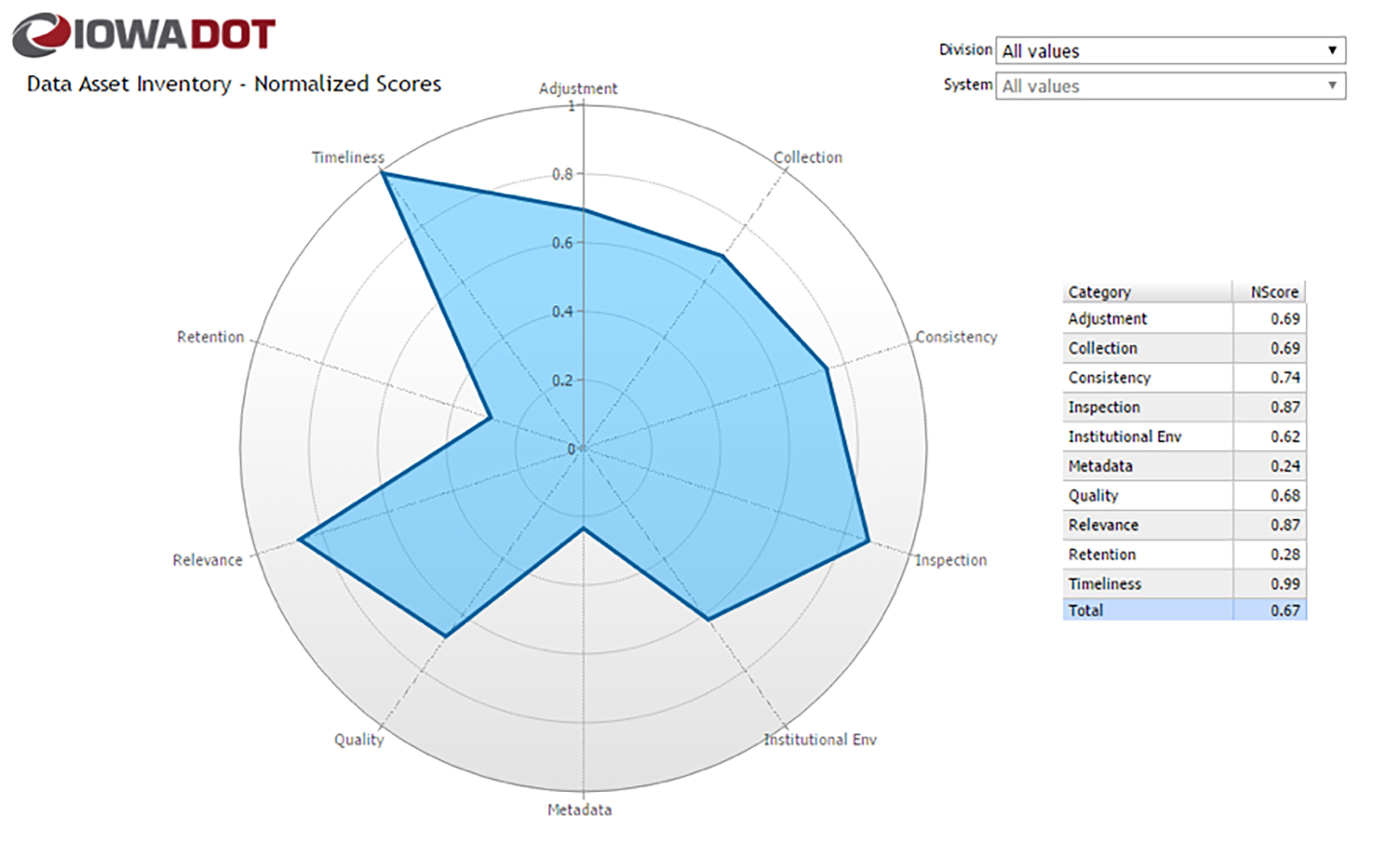

This subsection highlights the importance of effective data and information systems in supporting Transportation Asset Management (TAM) programs. It introduces the NCHRP Report 956 and AASHTO TAM Data Guide, which offer a structured approach for assessing current TAM data practices, identifying improvements, and planning implementation strategies. The guidance includes practical tips, supporting materials, templates, and real-world implementation examples to help transportation agencies enhance their TAM data management.

Overview

Transportation agencies are facing increasing pressure to make more effective use of data and information systems to support their TAM programs. Addressing this need, NCHRP Project 08-115 produced NCHRP Report 956, a Guidebook for Data and Information Systems for Transportation Asset Management. AASHTO hosts web-based versions of the guidebook and tools, where subsequent implementation guidance and DOT implementation experiences have also been shared.

Built upon a data life-cycle framework which addresses five distinct stages in the use of data for TAM, the NCHRP Report 956 and associated AASHTO TAM Data Guide provide a structured approach for transportation agencies to:

- Assess current TAM data and information system practices and establish a desired state.

- Identify and evaluate data and information system-related improvements.

- Secure agency support for improvements and plan an implementation strategy.

Figure 7.4 Stages in the Use of Data for TAM

This guidance is supplemented with valuable support materials, including:

- Practical implementation tips to support the TAM data and information system assessment, improvement selection and evaluation, and action planning processes.

- Supporting materials and templates (such as assessment scoping guidance, stakeholder engagement and facilitation materials, and assessment summary and action planning templates).

- User guidance, quick reference materials, and tutorial videos to guide tool use and application.

- Research implementation examples based on four real-world implementations of the guidance at the New Hampshire, New Mexico, and Virginia DOTs.

Other Related Methodologies

For those exclusively focused on better understanding and improving how they manage their TAM data, NCHRP Project 20-44(12) was completed in 2022, providing improved tools, supplemental guidance, materials, and detailed case studies on implementation of the NCHRP Report 814 Data Self-Assessment Guidance. The outcomes of this project included detailed agency-specific assessment experiences, including several applications of the data management maturity and data value assessment frameworks in TAM-specific contexts.

New Hampshire DOT

The New Hampshire DOT (NHDOT) was interested in improving data and information systems to enable better alignment between bridge preservation decision-making approaches with those used for bridge rehabilitation and replacement. This TAM Data Assessment was conducted in anticipation of advancements in data and modeling detail and better integration of bridge asset management and bridge design systems and models. At the time of the assessment, a new bridge management system was being implemented, presenting a unique opportunity to advance data and information system practices.

*Note: This practice example was derived from NCHRP Final Research Implementation Report 1076: A Guide to Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a Transportation Asset Management Plan. More TAM Data Assessment research implementation examples are available at: https://www.tamdataguide.com/research-implementation-examples/

New Mexico DOT

New Mexico DOT (NMDOT) had recently implemented a new data-driven methodology to prioritize proposed capital projects. The agency wanted to use the TAM Data Assessment to identify data and information system improvements to advance and sustain District implementation of the new approach and prioritization outcomes.

*Note: This practice example was derived from NCHRP Final Research Implementation Report 08-115: Guidebook for Data and Information Systems for Transportation Asset Management. More TAM Data Assessment research implementation examples are available at: https://www.tamdataguide.com/research-implementation-examples/

Virginia DOT

This TAM Data Assessment examined the Virginia DOT maintenance management system to identify how current functionality could be expanded to support broader asset management of roadside assets.

*Note: This practice example was derived from NCHRP Final Research Implementation Report 08-115: Guidebook for Data and Information Systems for Transportation Asset Management. More TAM Data Assessment research implementation examples are available at: https://www.tamdataguide.com/research-implementation-examples/

Virginia DOT

Virginia DOT (VDOT) has a long standing and high functioning Pavement Management program. This program is organized around a well-established pavement management system (PMS) and pavement maintenance scheduling system (PMSS). These systems are used by Central Office and District staff to forecast pavement conditions, allocate resources, and plan targeted preventative, corrective, and restorative maintenance projects. Although VDOT staff were confident in their program, they were motivated to identify if further improvement would be possible through data and/or system improvements.

*Note: This practice example was derived from NCHRP Final Research Implementation Report 08-115: Guidebook for Data and Information Systems for Transportation Asset Management. More TAM Data Assessment research implementation examples are available at: https://www.tamdataguide.com/research-implementation-examples/

Deciding What Data to Collect 7.2.1

Many organizations have recognized that data should be viewed as an asset. Before acquiring new data, it is important to establish a clear statement of how the data will be used and what value it is expected to provide.

Deciding what data to collect involves identifying information needs, estimating the full costs of obtaining and managing new data and keeping it up to date, and then determining whether the cost is justified. Just as agencies don’t have unlimited resources to repair and replace their assets, there are also limitations on resources for data collection and management.

A 2007 World Bank Study summarized three guiding principles for deciding what data to collect:

- Collect only the data you need;

- Collect data to the lowest level of detail sufficient to make appropriate decisions; and

- Collect data only when they are needed.

Chapter 6 can be used to help identify the information needed to track the state of the assets and investments to maintain and improve them. The basic questions one needs to answer to identify needed data are:

- What decisions do we need to make and what questions do we need to answer that require asset data? Typically, an organization needs to be able to answer questions including but not limited to its asset inventory, the conditions and performance of the inventory, and how resources are being spent on its assets. Also, an organization needs to determine what work is needed and how much that work will cost.

- What specific data items are required or desired? Next, one must identify the data required to meet the established information needs. There may be other data items that are not strictly required, but that may be useful if collected in conjunction with the required data. For instance, answering questions and making decisions regarding pavement an organization would typically want to have an inventory of existing pavement, details on paving materials used, and details on current conditions. Additional information on treatment history or substructure conditions might not be strictly required, but if available could enhance the decision-making process.

It is also important to incorporate standard data elements for location and asset identification into requirements, ensuring consistency with other asset data in the agency.

- What value will each data item provide? It is important to distinguish “nice to have” items from those that will clearly add significant value. The cost of collecting and maintaining a data element should be compared with the potential cost savings from improved decisions to be made based on the element. Cost savings may be due to asset life extension, improved safety, reduced travel time, or internal agency efficiencies. In addition, proxy measures for information value can be considered such as the number and type of anticipated users, and the number and type of agency business processes to be impacted.

- What level of detail is required in the data? Level of detail is an issue for all assets, but is particularly an issue for linear assets such as pavement, where one may decide to capture data at any level of detail. For instance, to comply with Federal reporting requirements for pavement condition a state must collect distress data at 1/10 mile intervals for one lane of a road (typically the outside line in the predominant direction). For other applications it may be necessary to collect data for additional lanes, or at some other interval.