Topic: Risk Management and System Resilience

Risk Management and System Resilience

This page features information on managing risk and building system resilience. Whether you are folding risk into the resource allocation process, evaluating performance measures with respect to risk, or assessing potential program adjustments, you will find what you need here.

Overview:

Implementation Considerations:

Related Subsections:

Risk Management 2.2.3

Managing transportation assets entails managing risk. This includes day-to-day concerns, such as addressing the risk that assets will deteriorate faster than expected or projects will cost more than budgeted. However, managing risk also involves enterprise-level risks with widespread impacts.

TAM Guide Book Club #5: Improving Risk Management and Resiliency

FHWA defines risk and risk management, in the context of transportation asset management, as follows:

- Risk: The positive or negative effects of uncertainty or variability upon agency objectives. (23 CFR 515.5)

- Risk Management: The processes and framework for managing potential risks, including identifying, analyzing, evaluating, and addressing the risks to assets and system performance. (23 CFR 515.5)

Considering risk is important in developing TAM strategies, because transportation agencies often must spend significant resources responding to and/or mitigating risks. Reacting to the uncertainty presented by risks can be more expensive than proactive management. Risk management strengthens asset management by explicitly recognizing that any objective faces uncertainty, and by identifying strategies to reduce uncertainty and its effects. Being proactive, rather than reactive, in managing risk and avoiding “management by crisis,” helps agencies best use available resources to minimize and respond to risk as well as further build public trust.

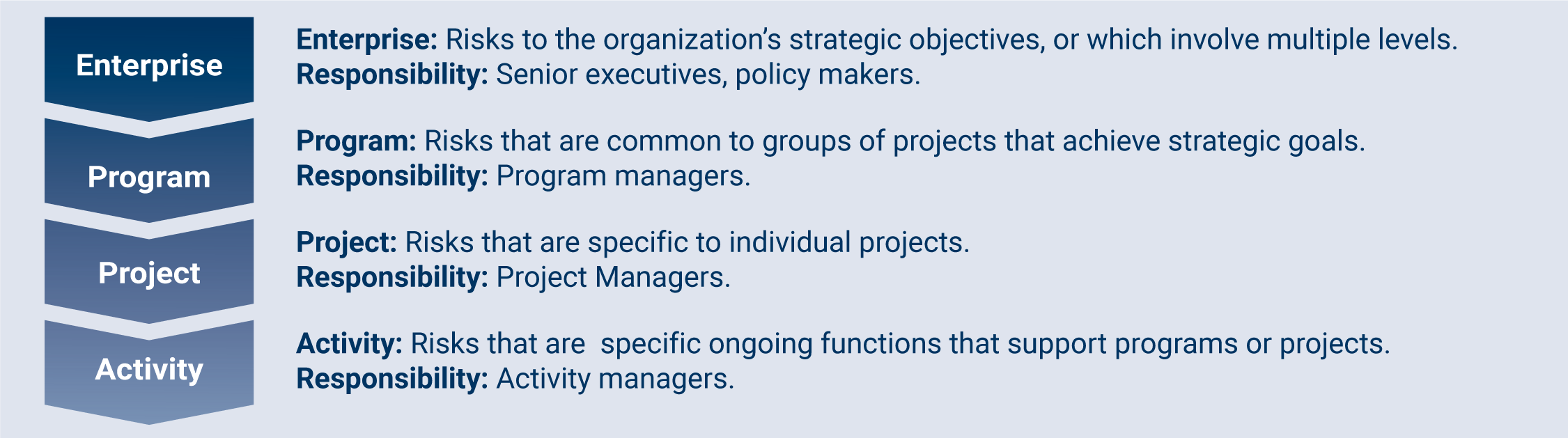

Given the importance of risk management for supporting asset management, agencies should formally identify and manage risks at all organizational levels. Figure 2.6 shows four levels at which risks can be identified within an agency, and the individuals who may be responsible for the risks at each level.

Typically agencies manage risk every day. They are well-equipped to hand risks at the project and activity levels, and regularly consider risks on a larger scale. Formally considering and documenting potential risks at all levels can help bring greater attention to them and improve risk management.

TIP

Risk management workshops or discussions should involve as many people in as many different parts of the agency as possible. This ensures that a broader range of risks and categories of risks are included.

Figure 2.6 Levels of Risk within an Organization

TRB. 2016. NCHRP Project 08-93 Final Report. http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/docs/NCHRP08-93_FullGuide.pdf

Risk Management Process

TAM Webinar #27 - Risk Management

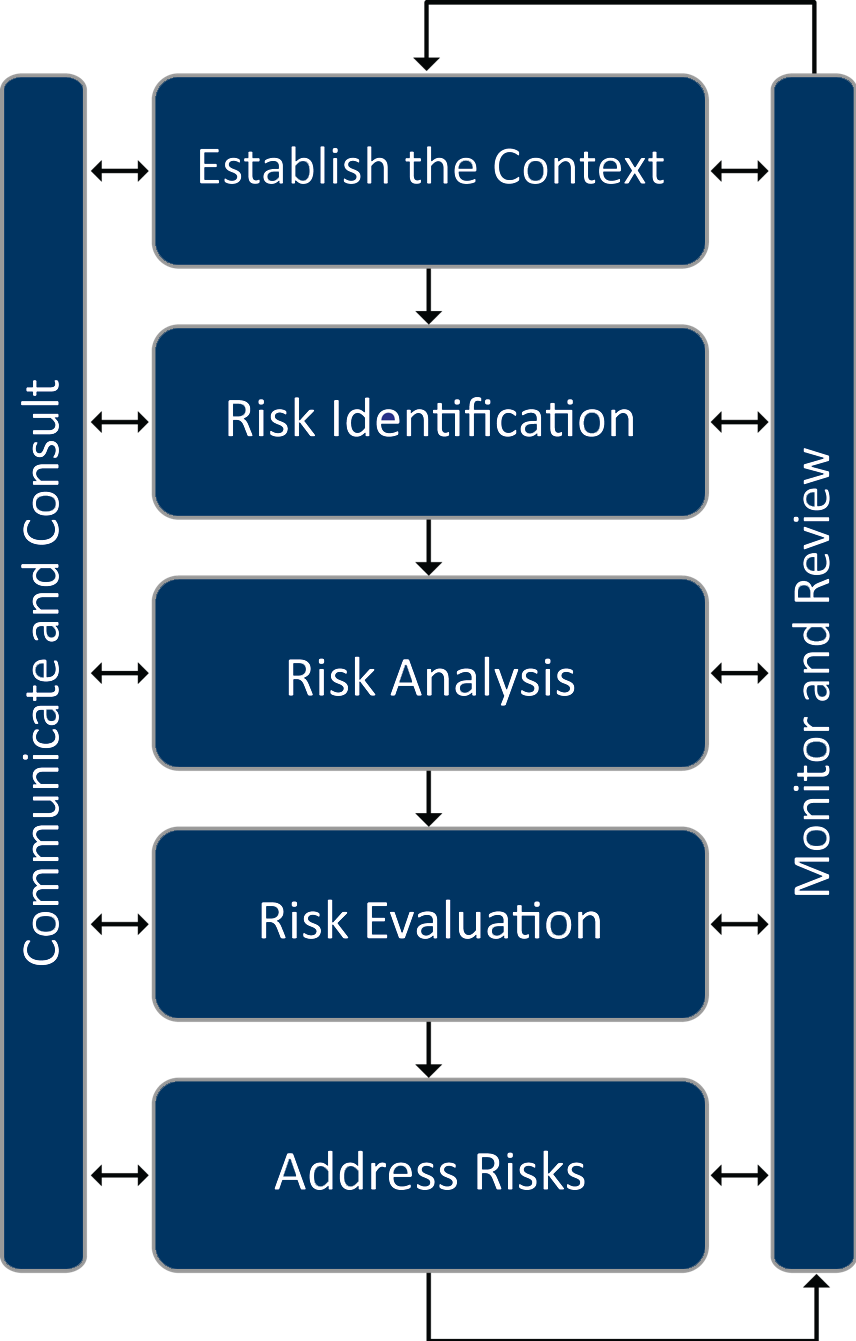

Figure 2.7 depicts a risk management process. While it may not be necessary to walk through each discrete step in this process for every risk an agency faces, this process is helpful for understanding how to incorporate risk into TAM.

- The process starts with establishing the context for risk management. In the case of risk management for a TAMP, the context is largely defined through other TAMP development steps.

- The second step involves identifying the risks that affect the assets in the TAMP. Ideally, in this step the agency considers the full set of asset-related risks, even those that may appear insignificant.

- The third step, risk analysis, involves identifying the cause of the risk, the outcomes or consequences (impact), and the likelihood of the risk occurring.

- The fourth step, risk evaluation, entails prioritizing and ranking risks.

- Fifth, the address risks step is the response the agency takes to the risk. DOTs can choose to tolerate the risk or treat the risk in some manner.

- The left side of the figure shows a continuous communication and consultation activity. Agencies need to communicate the risks to both internal and external stakeholders, as well as monitor and review the risks.

- The right side of the figure shows an iterative monitoring and review process. Once the risks are identified, analyzed, and a mitigation plan is in place agencies need to monitor the risks and update the risk management documentation accordingly.

- More on risk monitoring and management is discussed in Chapter 6 Monitoring and Adjustment.

- This process is generally consistent with ISO Standard 31000, as well as FHWA’s requirements for state DOTs to assess risks to NHS assets in developing a TAMP.

Figure 2.7 The Relative Timeframes Between Plans

Source: Adapted from FHWA. 2017. Incorporating Risk Management into Transportation Asset Management

Plans: Final Document. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/asset/pubs/incorporating_rm.pdf

Risk Register

It is common practice to develop a register identifying major risks and assess each based on expert judgment. In this fashion, the process is valuable for identifying “non-programmatic” risks, or risks not previously addressed in any one program. The How-To Guide in this section describes the steps in developing a risk register to identify such risks. Once a risk has been identified and assessed, formal processes may be required to perform a more detailed assessment and manage the risk programmatically, as illustrated in the Arkansas practice example.

Arkansas DOT

As part of the process of developing its 2018 TAMP, ARDOT developed a risk register and mitigation plan compliant with FHWA TAMP requirements. As part of this effort, ARDOT first reviewed and documented its existing controls for asset-related risks incorporated in its design specifications, and approaches for addressing specific risks to bridges (e.g., scour). The agency then developed an initial register through a risk workshop. In the workshop, ARDOT staff identified specific risks not otherwise addressed programmatically, classifying risks by type:

- Asset Performance

- External Threats

- Business Operations

- Highway Safety

- Finances

- Project and Program Management

- Information and Decision Making

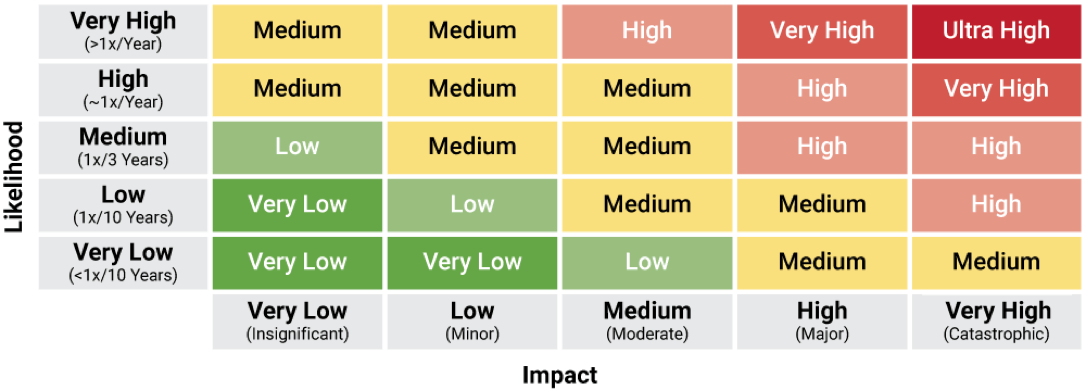

For each risk ARDOT used expert judgment to classify the risk in terms of its likelihood and impact. An initial priority was determined based on this classification. Next, ARDOT defined potential mitigation strategies for each of the 14 high-priority asset management risks in the register. A total of 12 strategies were identified, with each helping to mitigate one or more different risks. ARDOT next prioritized the mitigation strategies, and developed mitigation and monitoring plans detailing actions to be undertaken, and the approach for monitoring the risks and updating the register moving forward.

Arkansas DOT. 2018. ArDOT Risk-Based Transportation Asset Management Plan. http://www.tamptemplate.org/wp-content/uploads/tamps/037_arkansasdot.pdf

Connecting Resilience with Asset Management 2.2.5

This subsection emphasizes the critical connection between resilience and transportation asset management (TAM) in the face of increasing threats from extreme weather events and disruptions. It outlines six major components for integrating resilience into TAM, including developing objectives and targets, identifying and assessing risks, implementing resilience strategies, incorporating resilience into planning, and monitoring and evaluating resilience efforts to ensure effective mitigation of disruption impacts.

Overview

TAM Webinar #60 - TAM and Resilience Building: Takeaways from the TAM Peer Exchange

As transportation systems face increasing threats from extreme weather events, climate change, and other disruptions, integrating resilience into transportation asset management plans (TAMPs) is crucial for ensuring the continued performance and reliability of these vital networks. Transportation assets are vulnerable to disruptions that have become increasingly more common or more severe, such as those caused by extreme weather events, climate change, as well as disruptions from man-made hazards such as fires, industrial accidents or security- or cyber-threats-. To sustain the performance and reliability of transportation systems, it is essential to include resilience as a factor in transportation asset management practices.

In the context of transportation asset management, resilience refers to the ability of transportation assets to maintain their functionality and performance in the face of disruptions, as well as the ability of transportation systems to quickly recover from disruptions and restore service. Integrating resilience into a transportation asset management plan (TAMP) involves incorporating strategies to prepare for, withstand, and recover from disruptions caused by extreme weather events, climate change, and other hazards. This approach ensures that transportation assets remain functional and support community needs during and after disruptions.

Addressing resilience within a TAMP has the following six major components:

- Develop Resilience Objectives and Targets: Transportation agencies should develop resilience goals and objectives. These objectives and targets should be aligned with the overall goals of the transportation system and should be measurable and achievable. These objectives should focus on minimizing disruptions, reducing recovery time, and enhancing the overall resilience of assets. By setting specific targets, an agency can effectively track progress and make informed decisions about resilience investments.

- Identify Risk: A transportation agency needs to identify and assess the risks that its transportation assets face. This includes understanding the likelihood and severity of potential disruptions, as well as the potential consequences of those disruptions. Identifying potential hazards, such as floods, hurricanes, or earthquakes, and evaluating their likelihood, severity, and potential consequences for transportation assets are important.

- Assess Risk: Calculating and assessing risk involves considering the probability of occurrence, the potential damage, and the associated costs. The formula for calculating risk can be generally described as:

Risk = Probability of Occurrence × Damage × Cost

- Probability of Occurrence—The probability of occurrence is a measure of how likely it is that a particular event will happen. It is usually expressed as a percentage or a decimal between 0 and 1. For example, if there is a 20% chance of a flood occurring in a given year, the probability of occurrence would be 0.2.

- Damage—The damage is the extent of the negative impact that an event would have if it were to occur. This could include physical damage to assets, financial losses, or harm to people or the environment. Damage is often expressed in monetary terms, but it can also be qualitative.

- Cost—The cost is the amount of money that would be required to mitigate or recover from the damage caused by an event. This could include the cost of repairs, insurance premiums, or emergency response measures.

Once you have determined the probability of occurrence, damage, and cost, you can multiply these three values together to calculate the overall risk. The resulting value represents the expected financial impact of the risk.

- Identify and Implement Resilience Strategies: Transportation agencies should identify and implement a variety of resilience strategies to mitigate the impacts of disruptions. These strategies may include hardening assets, improving redundancy, and developing emergency response plans. Understanding the specific risks faced by your transportation network will guide the development of tailored resilience strategies.

- Incorporate Resilience into a TAMP: The resilience strategies and considerations should be incorporated into all aspects of transportation asset management planning, including asset inventory, condition assessment, and prioritization of investments.

- Monitor and Evaluate Resilience: Transportation agencies should monitor and evaluate their resilience efforts to ensure that they are effective in reducing the impacts of disruptions. This includes collecting data on asset performance, disruptions, and recovery efforts.

Resilience considerations should be integrated into all aspects of your TAMP, including asset inventory, condition assessment, and prioritization of investments. Consider the resilience implications of each decision and how it affects the overall resilience of your transportation system. For example, when prioritizing maintenance or replacement projects, consider the vulnerability of assets to disruptions and prioritize those that are critical for maintaining network connectivity or supporting emergency response efforts.

TPM Webinar #10 - Resiliency and the IIJA

Consideration of Risk in Resource Allocation 5.1.4

Uncertainty and risk complicate the resource allocation decision-making process. Risk management activities, including developing a risk register, are helpful in understanding and mitigating uncertainty, which in turn has implications for resource allocation.

Overview

All transportation decision-makers must contend with uncertainty. In regards to resource allocation, uncertainty is inherent in variables such as data on asset conditions and performance, future funding levels and costs, how a transportation system and specific assets will perform, and what external events or other factors may require reallocating resources. This uncertainty complicates efforts to make decisions about the future and forces agencies to be nimble so as to effectively respond to unpredictable events and evolving conditions.

In recent years, transportation and other industries have made significant progress developing improved approaches for managing uncertainty to minimize negative and leverage positive impacts. An area of focus in transportation has been in managing the risk of project cost and schedule overruns; a number of agencies have established enterprise risk management programs in order to address risk and uncertainty across their organizations. Likewise in TAM, there is increased interest in identifying and assessing risk so as to comply with both the best practices and the FHWA requirement for state DOTs to consider risk in developing their NHS TAMP.

The word ‘risk’ can be very context specific, meaning very different things depending on the industry and application. For instance, a financial analyst is primarily concerned with uncertainty in financial returns and the risk of incurring a significant financial loss. In the nuclear power industry, however, the focus of managing risk is on minimizing the potential for catastrophic loss that might occur from damage to a nuclear facility. As discussed in Chapter 2, in this guide risk is defined as the “effect of uncertainty on objectives” consistent with the ISO definition. This definition captures the full range of applications of risk management, and acknowledges the possibility for both positive and negative consequences of uncertainty.

The term ‘risk management’ is used to capture the set of business processes associated with identifying and managing uncertainty and risk. The overall risk management process is described in Chapter 2. The remainder of this section describes how this process relates to resource allocation.

Implications for Resource Allocation

While the scope of risk management may be very broad, an organization’s approach to risk management and the outcomes resulting from a risk assessment may nonetheless have important implications for TAM resource allocation. Consequently, it is important to establish a risk management approach and integrate consideration of risk with the resource allocation process.

TIP

Multi-objective decision making is a concept in operations research that is implemented in several different forms, from simple consensus-building approaches (e.g. Delphi processes) to more complex software tools. In all cases, it allows consideration of more than one factor or criteria in making a decision.

Specific possible implications of risk management on resource allocation may include, but are not limited to:

- An organization may identify through its risk management approach areas where better data or improved processes are needed to best address a given risk, in turn impacting the resource allocation process. For instance, if uncertainty concerning future asset conditions is found to be a significant risk, this may result in efforts to improve the deterioration models in an agency’s asset management systems and/or motivate data collection improvements to reduce uncertainty.

- An organization may identify specific investments of staff time and/or agency funds required to mitigate negative or leverage positive risk. Once specific investments are identified, they can be assessed along with investments in other asset/investment categories. For example, Caltrans defined a separate program for seismic retrofits as described in the Practice Example.

- If an agency’s allocation of resources hinges on uncertain future values for one or more parameters, it may be necessary to incorporate consideration of uncertainty formally in the decision-making process. This can be accomplished using Monte Carlo simulation or other quantitative approaches to establish the predicted distribution of outcomes. For instance, in performing a life cycle cost analysis to select between project alternatives for a given facility, Monte Carlo simulation can calculate the range of life cycle costs predicted depending on future values for cost escalation, deterioration, or other parameters.

- In approaching formal accounting for uncertainty, an organization may define different scenarios representing the possible range of outcomes and then determine how best to allocate resources in each scenario before establishing a preferred resource allocation approach. For example, if an agency’s future capital budget is unknown, a decision-maker may wish to define a high, medium and low budget scenario and determine what investments would be made in each scenario in order to most effectively prioritize given uncertainty. Likewise, a scenario analysis approach can be useful in assessing how to allocate resources for improving infrastructure resilience given uncertainty concerning future sea level rise. Typically, the decision maker will review results for different scenarios and make a subjective determination of how to allocate resources considering the relevant factors. The Practice Example describing the analysis of harbor-wide barrier systems for the City of Boston shows one such approach. Recent research in the area of Robust Decision Making (RDM) has focused on developing quantitative approaches to select optimal investments between different scenarios.

Caltrans

Caltrans initiated its Seismic Safety Retrofit Program in the wake of bridge failures experienced in the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Through this program Caltrans evaluated the retrofit needs for all of the over 12,400 bridges on the State Highway System (SHS). Retrofit needs were prioritized using a multi-attribute procedure that calculated a score for each bridge considering the likelihood of an earthquake at the bridge site, the vulnerability of the bridge to collapse in the event of an earthquake, and the impact of a collapse considering the traffic using the bridge and detour distance in the event of a collapse. Through 2014 the program resulted in retrofit of 2,202 state highway bridges at a cost of over $12.2 billion.

Sources:

2018 Caltrans TAMP

Practical Lessons from the Loma Prieta Earthquake (1994), p. 174-180 https://www.nap.edu/catalog/2269/ practical-lessons-from-the-loma-prieta-earthquake

University of Massachusetts

The Sustainable Solutions Lab at the University of Massachusetts Boston used a scenario-based approach to analyze the feasibility and potential risk reduction of Boston Harbor barrier systems to protect the Boston area from future flooding due to sea level rise. The report included an economic analysis in which costs and benefits were predicted for 32 scenarios considering:

- Two barrier system alternatives

- Two construction time scenarios

- Two scenarios for effectiveness of “shore-based solutions”

- Low and high construction cost estimates

- Discount rates of 3% and 7%

The analysis indicated that the benefits of the proposed barrier system would exceed their cost for both systems evaluated, but only in the case that one assumed a low discount rate, accelerated construction schedule, and failure of other shore-based solutions for mitigating sea level rise. Also, the analysis indicated that beyond a certain point sea level rise would be such that a barrier system would no longer prove effective (since the barrier would have to be closed at all times rather than only during flood events). The report further predicted costs and benefits for two alternative scenarios involving incremental adoption of a variety of shore-based mitigation approaches, and recommended an initial focus on shore-based adaption as the most promising strategy for the City of Boston to address sea level rise.

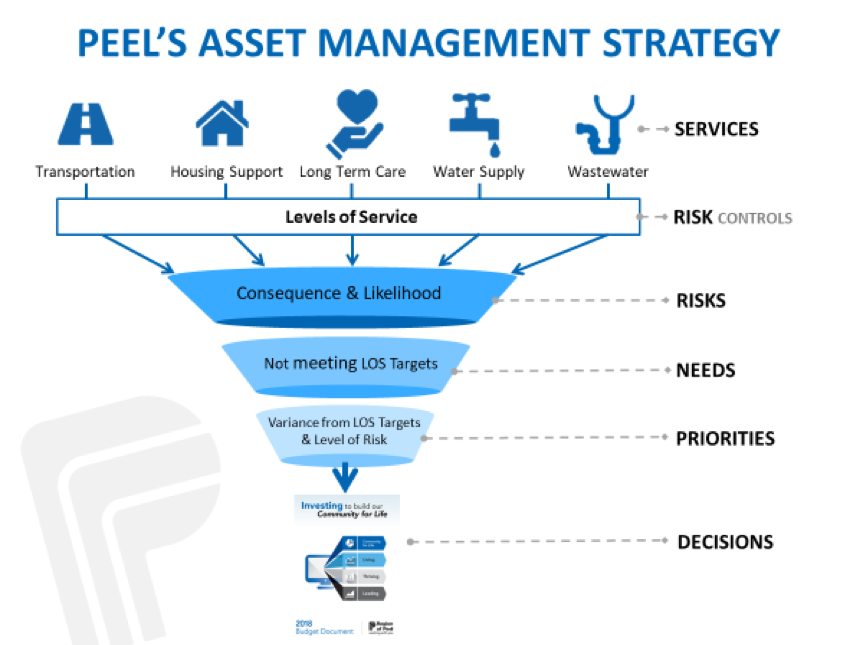

Regional Municipality of Peel (Canada)

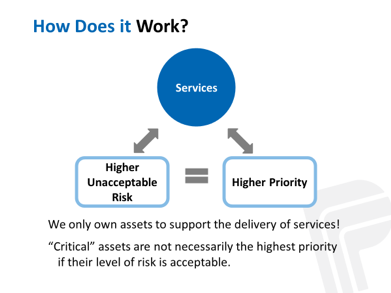

The Region of Peel is the second largest municipality in Ontario, just west of Toronto and supports two cities and a town. Peel assesses needs and priorities across a diverse portfolio of Infrastructure that supports a variety of programs and services including an arterial roads network, solid waste management, water and wastewater treatment distribution and a variety of social, health and emergency services. The Region integrated a number of inputs to enable an optimized investment methodology including a Risk Management, Level of Service, and Life cycle Management Strategies and priortize needs across diverse infrastructure, as illustrated in the figure. The integration of these three strategies was possible through three enablers and working with all of the programs and services to model their infrastructure:

- Establishing a consistent approach to quantifying risk – The Region evaluates the degree of risk that is currently being accepted associated with delivering service levels. Inherent risk (similar to asset criticality) and residual risk (the Region’s risk objective) are established and the current level of risk that an asset presents to service delivery is also determined. The gap between current and residual risk represents the unmet funding and asset needs.

- Establishing a normalized method to determine current level of service to assist the cross-asset funding allocation task. The adopted normalized indicator was determined to be: LOS=% of Assets Meeting LOS + (% of Assets Not meeting LOS x Average Condition of Assets not meeting).

- Adopting a direct relationship between LOS and risk that allows for an analysis of alternative investment scenarios, and modeling techniques to optimize investment allocation. It also allows annual infrastructure evaluation based on the most current condition information and annual Asset Management Reporting.

Peel’s risk-based approach to asset management is integrated with the Region’s Strategic Plan and the Long-Term Financial Planning Strategy, and supports the desired service outcomes by evaluating risk against the Council approved asset levels of service. This approach provides senior decision-makers an objective way to consider resource allocation alternatives and communicate in a common language when evaluating between service areas and different asset portfolios.

Peel Enterprise Asset Management Plan. 2019. http://www.peelregion.ca/council/agendas/2016/2016-04-07-arc-agenda.pdf. http://www.peelregion.ca/finance/_media/2019-enterprise-asset-management-plan.pdf

Monitoring and Managing Risks 6.5.1

Risk registers, risk reports, and risk mitigation plans are commonly used tools to track and manage risks. This section describes and illustrates each of these tools.

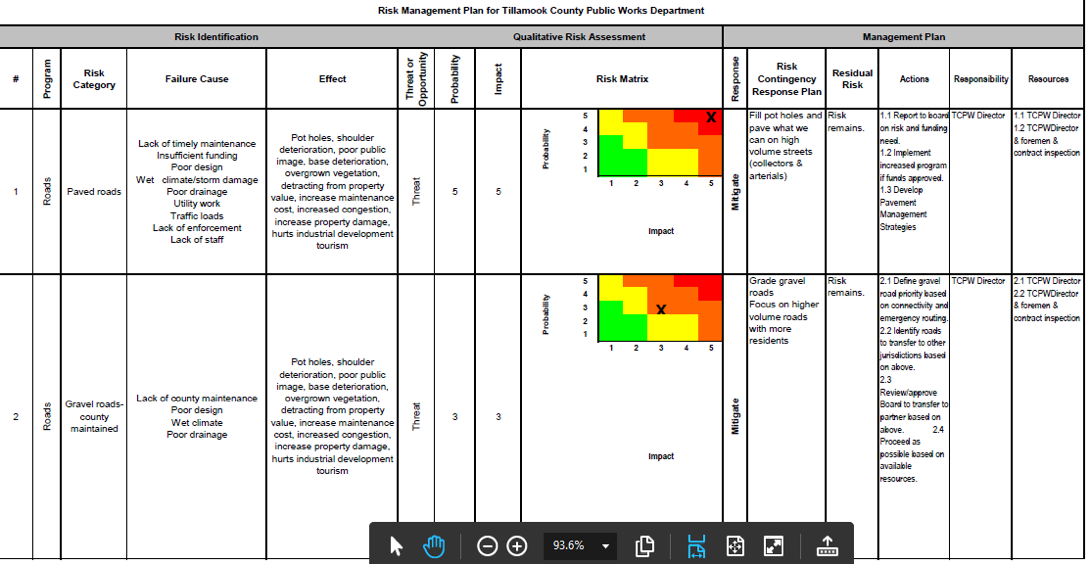

Risk Register

A risk register is one of the most common tools for tracking and managing risks within an agency, since it provides a framework for capturing critical information about each risk, its importance to the agency, mitigation plans and tracking and managing responsibilities. A risk register is typically generated as a spreadsheet, though other formats are available. An example of a comprehensive risk register, which includes assignments for risk mitigation strategies, is presented in Figure 6.4. Over time, columns may be added to indicate when the risk information was last updated, what further action is required and whether adequate progress is being made towards the mitigation strategy.

A risk register should be reviewed at least quarterly to evaluate whether the risk register or the risk management plan for any of the performance areas needs to be updated. Periodic changes to the risk profile may be obtained through executive staff meetings meant to evaluate progress regularly, or ongoing reports tracking risk mitigation efforts and results. Annually, the agency may determine whether any strategic-level risks should be adjusted based on evaluation of the agency’s performance and the risk reports provided by the risk owners.

Figure 6.4 Excerpt from a Risk Register Showing Responsibility for Risk Mitigation Activities

Source: Tillamook County Public Works Road Asset Management Plan. 2009.

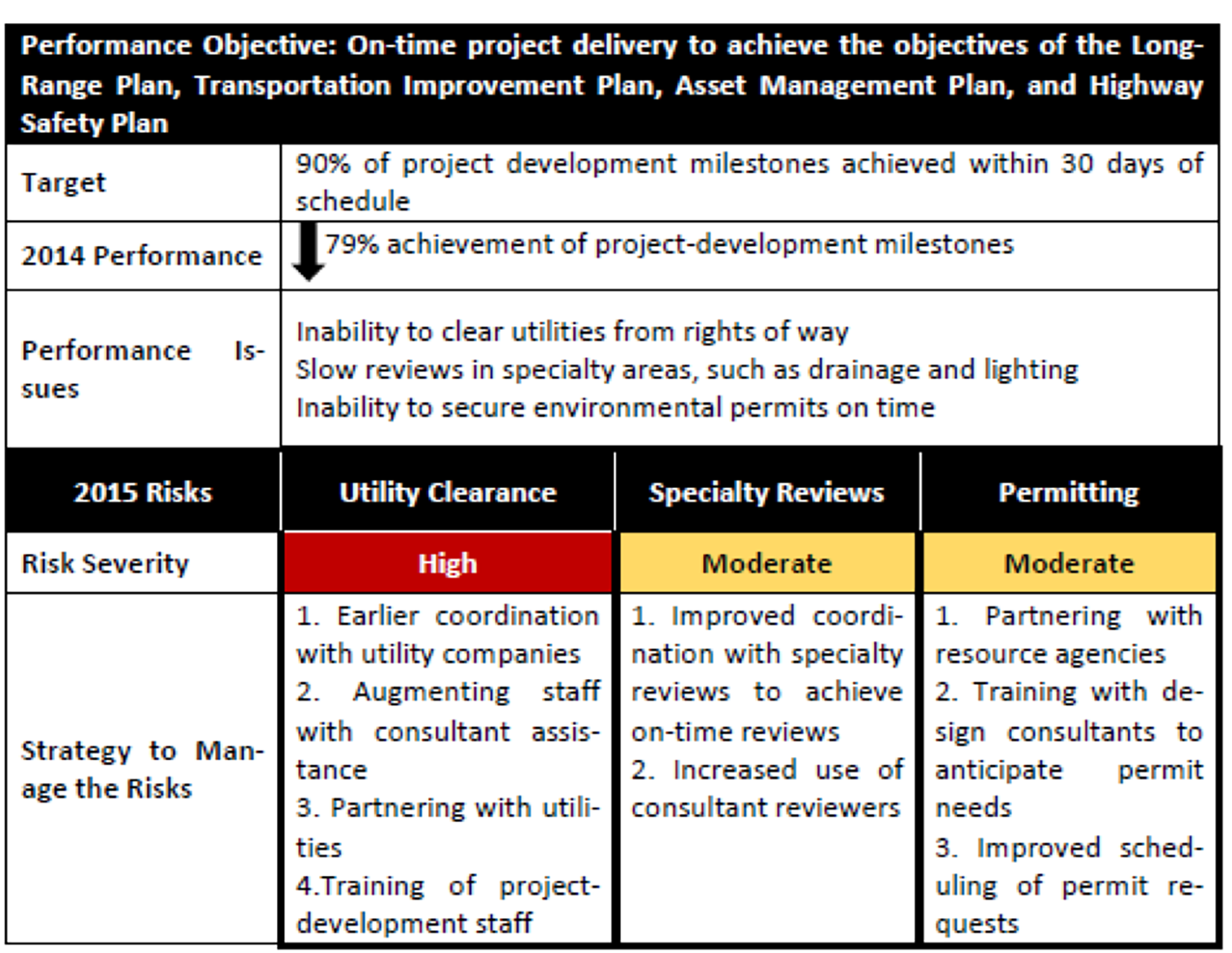

Risk Reports

Risk reports, which reflect excerpts from the risk register, may be developed by risk owners to communicate ongoing activities and manage risks at any level of the organization. The type of risk report shown in Figure 6.5 conveys what steps are being taken to address project delivery risks.

TAM Webinar #50 - Improving Your Next TAMP Miniseries: Improving Risk Management and Resiliency

Risk Mitigation Plans

Some agencies see benefit in developing risk mitigation plans for their assets to ensure compliance with regulatory programs and help embed risk into all agency business activities. For example, a risk management plan may be developed when a bridge’s risk of failure reaches a certain threshold. These plans identify specific risks and mitigation strategies to undertake in order to reduce the likelihood or impact associated with the risk.

Figure 6.5 Sample Risk Report

Source: AASHTO. 2016. Managing Risk Across the Enterprise: A Guide for State DOTs.

Washington State DOT

The Washington State DOT recognized the potential safety risk to highway travelers and the adverse impact on regional commerce associated with unstable slope failure. To become more proactive in managing this risk, WSDOT developed the Unstable Slope Management System (USMS) that provides a method for evaluating known unstable slopes and using the information to prioritize slopes for funding of proactive stabilization efforts. The mitigation objective of the unstable slope management program is to sustain a desired state of good repair and low risk over the life span (> 20 years) of known unstable slopes and constructed geotechnical assets at the lowest practicable cost.

Bay Area Rapid Transit Authority (BART)

BART developed a Local Hazard Mitigation Plan in 2017 to reduce or eliminate long-term risks to human life and property related to hazards such as earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides, flood, sea level rise, wildfire, and drought. The analysis focused primarily on high-priority fixed assets such as passenger stations, substations, switching stations, train control rooms, shops/yards, ventilation structures, and emergency exits. These assets were prioritized based on criticality in terms of the impact of an asset failure on reliable and safe service capabilities. The Local Hazard Mitigation Plan details the potential impacts associated with each hazard type and presents prioritized mitigation actions that were determined by votes from the participating members of a Task Force Committee called the Emergency Preparedness Task Force Committee (EPTFC) that is made up of senior managers from all BART departments. The plan is updated at least once every five years. An example of the type of mitigation strategies that were developed are presented in the Figure below. The Plan has helped identify agency priorities that are being addressed and has fostered collaboration among different Departments to reduce potential hazards.

Lessons Learned from Implementing Risk Management

Following the 2016 publication of the AASHTO Guide for Enterprise Risk Management, TRB initiated an NCHRP project to pilot the framework introduced in the Guide. Pilot case studies were conducted by the Tennessee, Utah, and Washington State DOTs; a peer exchange was conducted; and a national community of practice (COP) was formed to provide support for the implementation of risk management and to advocate for further research in this area. Several risk management tools were developed through the research that are documented in the NCRHP report.

A variety of different types of risks were considered during the pilot studies. The Tennessee DOT focused primarily on three types of risks:

- Those associated with inconsistencies in quick-clearance processes associated with crashes and other highway incidents.

- Those associated with roadway plans that could affect the quality, cost, and schedule for delivering projects.

- Those caused when incomplete project plans are submitted for bids.

Several tools were developed to better manage these risks, including checklists, plan submittal delay forms, and a Memorandum of Understanding with the Tennessee Department of Safety to clarify roles and responsibilities for quick clearances.

The Utah DOT pilot addressed four initiatives:

- Reduce risks to Utah DOT objectives by improving hiring practices and retention.

- Reduce risks of poor performance by enhancing the employee evaluating process and strengthening leadership skills.

- Reduce risks of poor performance through a knowledge management process.

- Develop a repeatable and scalable process to assess corridor risks caused by natural disasters.

The study improved leadership access to information for hiring and leading employees, provided a training toolkit for supervisors, and resulted in a process to integrate and incorporate risk and resilience assessments into existing decision-making processes.

Washington State DOT used the pilot to support the full integration of its enterprise risk management practices. The agency also elected to address cultural sensitivity and inclusion in workforce development activities. These efforts resulted in new workforce development and outreach materials.

The pilot studies helped expose the participating agencies to strategies for managing risk. They demonstrated the importance of promoting enterprise risk management concepts among agency leaders to mainstream the concepts into common agency practices. This increases the likelihood that enterprise risk management practices endure beyond changes in agency leadership.

The participants also recognized important links between risk management and both performance and asset management programs. Several agencies recognized the importance of risk management to improving the resilience of a highway network to unexpected events such as flooding or erosion. The pilot studies demonstrated that the ability to use risks to inform planning and investment decisions can be beneficial.

Managing Implementation Responsibilities and Processes 6.5.3

Monitoring the implementation of new business processes benefits from a clear definition of roles and responsibilities. This section illustrates approaches that agencies use to assign responsibility for implementation activities so that progress can be tracked.

Assigning Responsibility for Managing Risks and Implementation Activities

A key step in managing risks and other implementation activities is establishing a set of roles and responsibilities for each of the tasks at hand. The risk management process introduced in Chapter 2 includes a step for monitoring risks on a regular basis through a risk register or some other format.

Risks

When assigning responsibilities for managing risks, different types of risks are normally assigned to different individuals or divisions within a transportation agency:

- Strategic risks – Impact the agency’s ability to achieve its goals and objectives. Ignoring risks at this level can cascade down to impact programs and projects at other levels of the agency. For this reason, strategic risks are generally assigned to members of agency leadership and may be addressed by incorporating risks into regular management meetings and key policy documents.

- Program risks – Impact an organization’s ability to administer a program in a coordinated way. Risks at this level are typically the responsibility of the program manager ensuring there are effective controls over risk and documenting risk activities.

- Project risks – In many agencies, a project risk management process is in place with responsibility for managing risks assigned to the project manager. At this level, primary responsibilities include managing risks associated with the project scope, schedule and quality.

- Activity risks – Associated with routine activities performed by the agency, such as snow and ice control, incident response and pavement management modeling. Risks at this level are typically managed and monitored by the activity leader.

An agency may elect to appoint a Chief Risk Officer or to create an Enterprise Risk Unit charged with coordinating the agency’s risk processes and training agency personnel on risk management. If such a unit is created, the Chief Risk Officer often reports directly to the agency’s chief executive officer or another high-ranking executive, symbolizing the importance of risk management to the agency. Agencies without a formal Risk Unit may rely on the Asset Management Coordinator to serve in this role. Examples showing how risk roles and responsibilities have been assigned are provided in Figures 6.8 and 6.9.

Process Improvements

The success of a TAM Improvement Plan that outlines steps the agency plans to take to enhance its asset management program will also benefit from a clear set of roles and responsibilities for:

- Implementing the suggested changes,

- Monitoring progress, and

- Repeating the assessment periodically.

Ownership for the implementation of the planned enhancements generally lies with the TAM Coordinator in an agency, with specific tasks assigned to one or more individuals with the specialized skills and capabilities that are needed.

A major function of the implementation leader is to ensure that all roles are understood and that the various assignments are being carried out as intended. This may require building buy-in among the team members, who are likely busy with other responsibilities. It is also important that the leader have the authority responsibility to hold individuals accountable for progress, even if they report to a different division within the agency.

Table 6.4 Risk Types and Owners

| Risk Levels | Owners | Types of Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Risks | CEO Senior Staff Board or Commission |

|

| Program Risks | Leaders of major programs, such as safety, pavement, bridge, maintenance, information technology, project delivery, human resources |

|

| Project Risks | Project Managers |

|

| Activity Risks | Activity Managers |

|

Source: Transportation Research Board. 2014. Managing Risk Across the Enterprise: A Guide for State DOTs.

The availability of adequate resources is also important to the successful implementation of an improvement plan. Establishing clear role descriptions that describe the required tasks to be completed and the requirements needed to implement the changes enables an agency to compare the availability of existing staff to the implementation requirements. In some instances, staff may be temporarily assigned responsibility for a particular activity, such as developing a TAMP, to address a specific need.

Table 6.5 Risk Management Roles and Responsibilities for the Highways Agency, England

| Project Manager |

|

| Project Team Member |

|

| Project Risk Manager |

|

| Risk Owner (Action Owner) |

|

Source: Washington State DOT. 2018. Project Risk Management Guide.

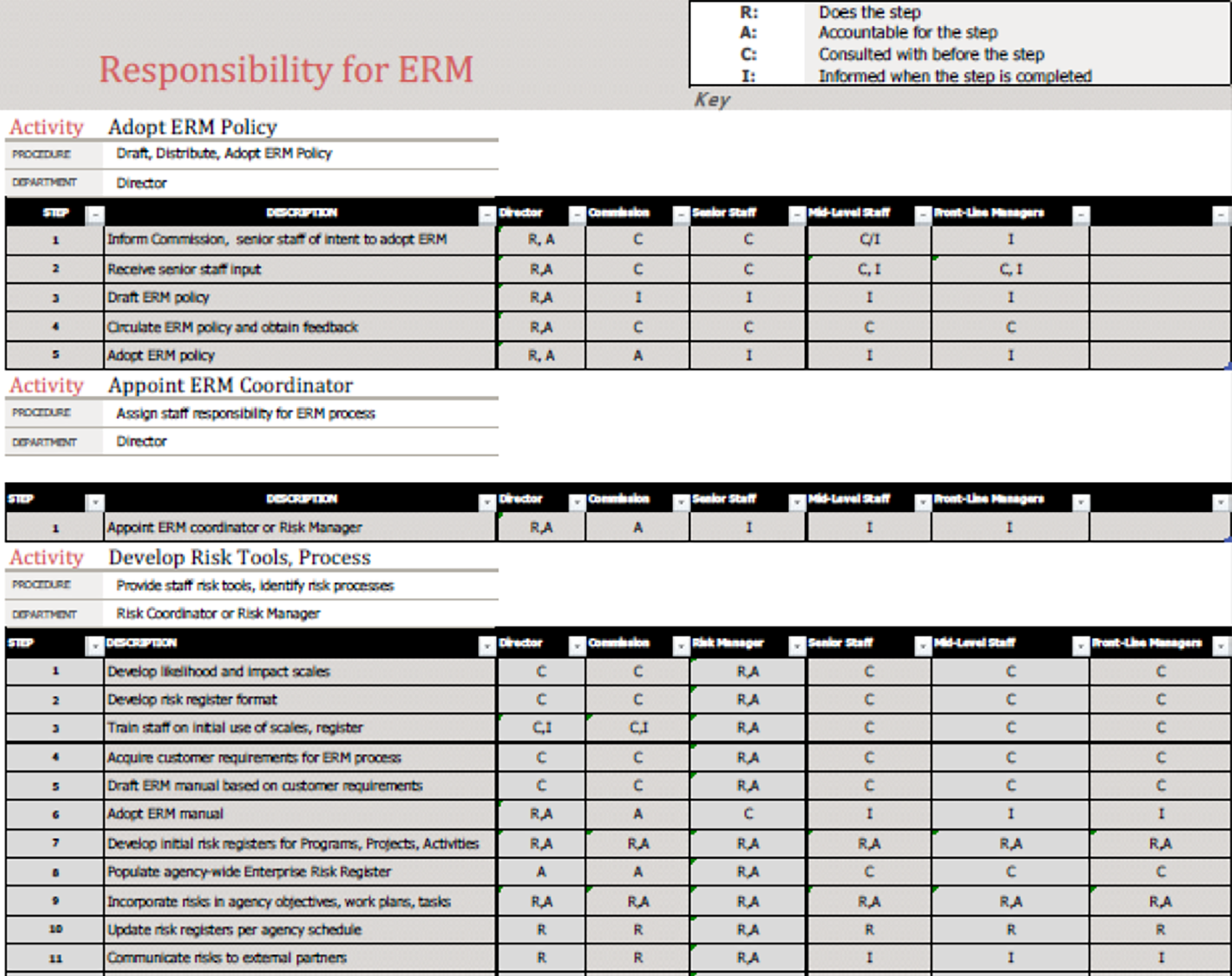

Using a RACI Matrix to Assign Roles and Responsibilities

A variety of tools can be used to track roles and responsibilities, including spreadsheets or various type of matrices. One form of responsibility assignment matrix is known as a RACI matrix. The term RACI is taken from the words:

- Responsible. Assigning responsibility for getting the work done or making a needed decision. This is typically the person who gets the work done.

- Accountable. Identifying the person who is responsible for making sure the work is done and is ultimately answerable for the activity or decision.

- Consulted. Recognizing that others will provide information needed to complete an activity.

- Informed. Keeping people aware of progress that is made.

A RACI matrix can be used for virtually any type of activity with a combination of tasks, milestones, and key decisions that will be carried out by several different individuals. It is a common technique used for managing different types of construction, implementation, and monitoring activities and is especially useful when responsibilities are divided across divisions or departments within an organization. For that reason, it is commonly used as part of an enterprise-wide risk management program to help ensure that risks are monitored regularly. An example of a RACI matrix showing responsibilities for adopting an enterprise risk management (ERM) policy is shown in figure 6.7.

Figure 6.7 Example RACI Chart

Source: AASHTO. 2016. Managing Risk Across the Enterprise: A Guide for State DOTs.

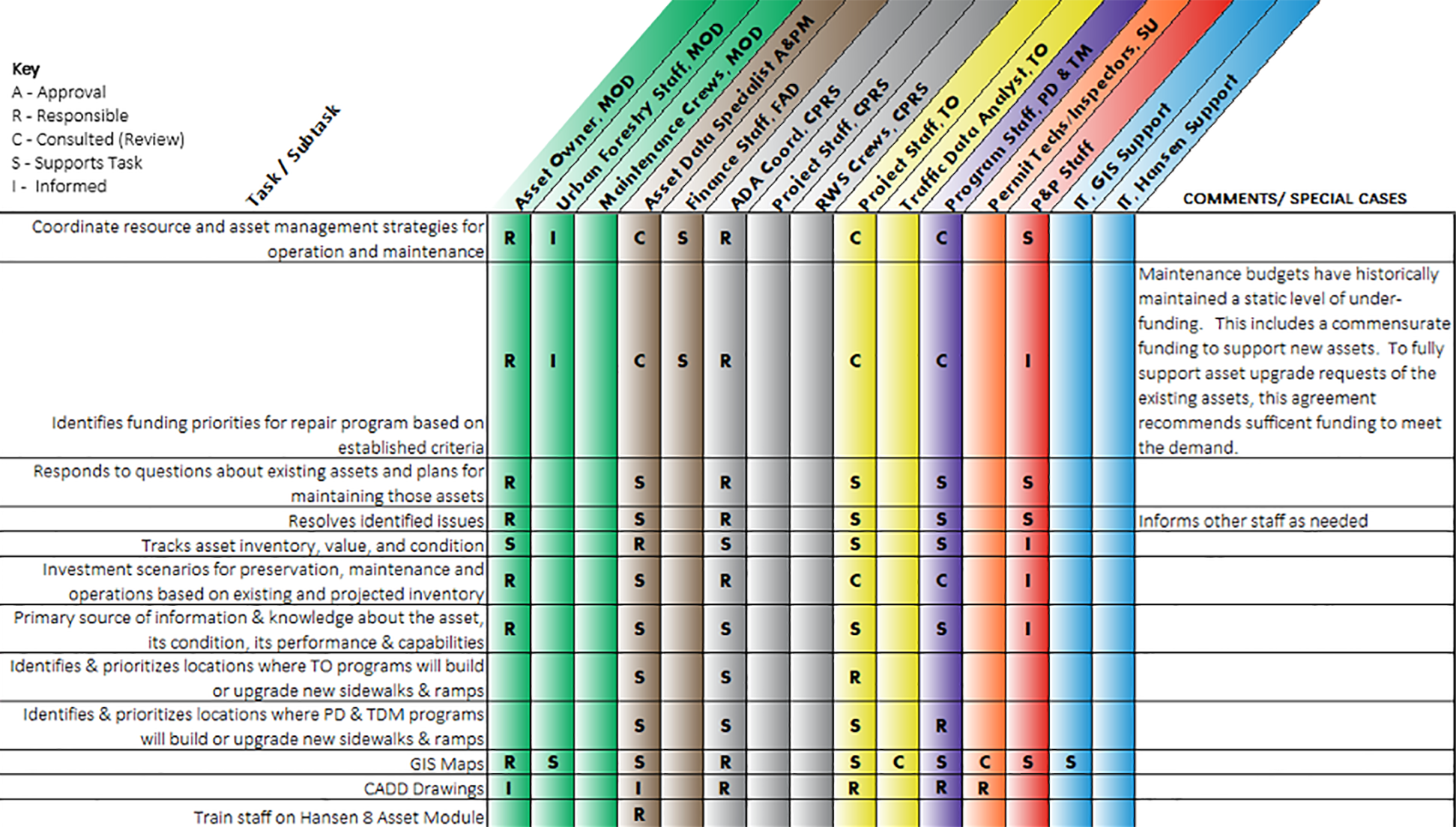

Seattle DOT

The City of Seattle has a Sidewalk Safety Repair Program to oversee the maintenance of the City’s many sidewalks and curbs to keep them safe and accessible. The Program includes a process for monitoring sidewalk conditions, investigating complaints of unsafe or inaccessible sidewalks, determining repair responsibility (e.g.., adjacent property owner, City, or other utility), using existing conditions to proactively mitigate conditions (beveling and asphalt shimming), and permanently repairing sidewalks that are the City’s responsibility. Repairs are leveraged with other capital projects as much as possible, so coordination with other Divisions is vital to the effectiveness of the program.

Because of the number of Divisions involved in managing sidewalks, the City assigned roles and responsibilities in a RACI matrix, that identifies those with Responsibility (R) or Accountability (A), those that need to be Consulted (C), and those that need to be Informed (I). The RACI matrix developed by the City includes one additional role beyond the four that are commonly included in the matrix. The City of Seattle added an “S” to represent a support role for personnel who might provide information to the process but are not necessarily responsible for completing the activity. The RACI matrix has served the City well by clarifying the responsibilities of each of the Divisions involved in some aspect of the Program so the program looks seamless to the public, as shown on the City’s website (https://www.seattle.gov/transportation/projects-and-programs/programs/maintenance-and-paving/sidewalk-repair-program).

Excerpt From a RACI Matrix Developed by the City of Seattle for Managing Roles and Responsibilities for its Sidewalk Repair Program

Source: City of Seattle. 2019.

Practice Examples:

Arkansas DOT

As part of the process of developing its 2018 TAMP, ARDOT developed a risk register and mitigation plan compliant with FHWA TAMP requirem…

Colorado DOT

Risk-Based Rock-Fall Management Program

Colorado DOT responds to between 50 and 70 geotechnical emergencies a year. The traditional approach to managing rockfalls was based on t…

Caltrans

Caltrans initiated its Seismic Safety Retrofit Program in the wake of bridge failures experienced in the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Thr…

University of Massachusetts

Analysis of Harbor-Wide Barrier Systems

The Sustainable Solutions Lab at the University of Massachusetts Boston used a scenario-based approach to analyze the feasibility and pot…

Regional Municipality of Peel (Canada)

The Region of Peel is the second largest municipality in Ontario, just west of Toronto and supports two cities and a town. Peel assesses …

Washington State DOT

Managing the Risk of Unstable Slope Failure

The Washington State DOT recognized the potential safety risk to highway travelers and the adverse impact on regional commerce associated…

Bay Area Rapid Transit Authority (BART)

BART developed a Local Hazard Mitigation Plan in 2017 to reduce or eliminate long-term risks to human life and property related to hazard…

Practices:

Cross Asset Resource Allocation

- Basic decision support tools are embedded across the organization and used to qualitatively inform decision-making for funding allocation between asset classes.

- Multi-objective allocation approaches are being considered or trialed to allocate funding across asset classes to balance risk, service delivery and investment.

- Service levels and associated performance measures are evaluated and considered for allocation decisions

- Decision support tools including computerized systems are being procured or implemented to inform decision-making for funding allocation in the future near term.

- Appropriate multi-objective allocation approaches are established in the agency and employed to allocate funding across asset classes to balance risk, service delivery and investment.

- Service levels and associated performance measures are evaluated and linked directly with allocation decisions

- Decision support tools including computerized systems are embedded across the organization, and used to inform decision-making for funding allocation.

Tracking and Managing Risks

- The agency has identified some operational risks, manage them in a risk register and have established targeted mitigation strategies.

- The agency has an integrated risk management framework that allows risk to be employed at a more than one level within the agency.

- High risks are proactively managed or leveraged.

- The agency has an integrated risk management framework that allows risk to be employed at strategic, tactical, and operational levels.

- Risks are proactively managed or leveraged.

- Managed risks show reduced frequency of negative consequences or opportunities are captured as appropriate.

- TAM processes are evaluated regularly for improvement.

How To Guides:

Develop a Risk Register

Manage Change and Prepare for a System Replacement

How to Prioritize Ancillary Assets for Inclusion in Your Asset Management Program

Methods of Monitoring Financial Risks in a TAMP

Checklists:

Identifying and Assessing Risks

Monitoring External Considerations in Risk

Risk Management Process

December 1, 2017 | FHWA

The Federal Highway Administration’s Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Framework is a manual to help transportation agencies and their partners assess the vulnerability of transportation infrastructure and systems to extreme weather and climate effects. It also can help agencies integrate climate adaptation considerations into transportation decision-making.

External Link: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/sustainability/resilience/adaptation_framework/

December 6, 2022 | FHWA

This tool provides a series of climate change adaptation case studies. Use this search tool to narrow down the list of studies, or select "All Records" to see all of the case studies on file.

External Link: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/sustainability/resilience/case_studies/

January 10, 2022 | Transportation Research Board

Research and practice in the areas of transportation performance, risk, and asset management have added to the tools, methods, and strategies available to state departments of transportation and other transportation agencies. Fundamentally changing the culture of a transportation agency and integrating those changes into historically siloed management practices requires the earnest focus of the entire organization, including participation of practically every individual.

External Link: https://www.trb.org/Publications/Blurbs/182511.aspx

January 1, 2021 | Transportation Research Board

The TRB National Cooperative Highway Research Program's NCHRP Research Report 986: Implementation of the AASHTO Guide for Enterprise Risk Management documents how several state departments of transportation are adopting risk management principles and practices.

External Link: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26516/implementation-of-the-aashto-guide-for-enterprise-risk-management

April 1, 2023 | FHWA

This handbook is designed to help transportation practitioners incorporate natural hazard resilience into asset management. It summarizes who to include in this planning process and how different groups can work together on this topic.

External Link: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/asset/pubs/hif23010.pdf

January 1, 2021 | Transportation Research Board

Transportation System Resilience: Research Roadmap and White Papers highlights significant knowledge gaps within AASHTO and state departments of transportation, presents a 5-year research plan that addresses these gaps, and discusses critical resilience-related issues facing senior transportation leaders today.

External Link: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26160/transportation-system-resilience-research-roadmap-and-white-papers

January 1, 2021 | Transportation Research Board

Resilience Primer for Transportation Executives provides a quick grounding in resilience benefits, the CEO’s role in resilience, and approaches taken in various states to increase the resilience of their transportation system. It also offers concepts and tools to lead agencies toward greater resilience.

External Link: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26195/resilience-primer-for-transportation-executives

January 1, 2021 | Transportation Research Board

Mainstreaming System Resilience Concepts into Transportation Agencies: A Guide provides transportation officials with a self-assessment tool to assess the current status of an agency’s efforts to improve the resilience of the transportation system through the mainstreaming of resilience concepts into agency decision-making and procedures. The tool can be applied to a broad array of natural and human-caused threats to transportation systems and services.

External Link: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26125/mainstreaming-system-resilience-concepts-into-transportation-agencies-a-guide

January 4, 2022 | Springer Cham

This book introduces readers to the key provisions of the URRAN-based technical asset management system - a methodology for managing resources and risks by analyzing and ensuring the required levels of reliability and safety in Russia’s railway transport facilities. It describes the architecture of the URRAN information system’s unified corporate platform (UCP URRAN) and its subsystems for infrastructure facilities and rolling stock complexes.

External Link: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-90029-8

February 1, 2021 | FHWA

This case study summarizes some of the good risk management practices used by various state DOTs.

External Link: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/55725

August 1, 2023 | FHWA

This report builds on information gathered from developing state DOT case studies on identifying and managing financial risks. This report summarizes the common financial risks considered in state DOT TAMPs and how these factors influence the development of TAMP investment strategies.

External Link: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/asset/pubs/hif23049.pdf

January 1, 2022 | FHWA

Implementation of the AASHTO Guide for Enterprise Risk Management documents how several state departments of transportation are adopting risk management principles and practices.

External Link: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26516/implementation-of-the-aashto-guide-for-enterprise-risk-management

January 1, 2022 | Transportation Research Board

Integrating Effective Transportation Performance, Risk, and Asset Management Practices is designed to be a process framework that is resilient to the expected evolution of an agency as it matures in its management integration.

External Link: https://www.trb.org/Publications/Blurbs/182511.aspx

January 1, 2022 | FHWA

Implementation of the AASHTO Guide for Enterprise Risk Management documents how several state departments of transportation are adopting risk management principles and practices.

External Link: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26516/implementation-of-the-aashto-guide-for-enterprise-risk-management

January 1, 2022 | USDOT OST-R

This project develops a comprehensive analytical framework for risk-based infrastructure asset management for both normal and extreme management conditions.

External Link: https://cait.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/cait-utc-reg-38-final_v3.pdf