- Chapters

-

Chapter

3

Sections - Chapter 3 Executive Summary

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 3

Quick Links

Chapter 3

Organization and People

Asset Management is not possible without the people within the organization who commit to its success. An improved understanding of the various organizational models that support TAM can accelerate an agency’s ability to add value through its TAM program and sustain value into the future. In addition, a clear understanding of roles and responsibilities and their interaction can strengthen TAM implementation. This chapter covers the organizational and people elements that support the asset management process.

Section 3.1

Establishing TAM Roles, Responsibilities, and Competencies

Identifying a “home” for asset management within the organization is also an important decision agencies need to make. Defining the roles and responsibilities required for asset management is an important step in ensuring a TAM program’s success. Regardless of what organizational model is used to fit asset management within an agency, there are key competencies that should be established as well.

Section 3.2

Strengthening Coordination and Communication

Section 3.3

Managing Change

In general, TAM implementation or advancement involves introducing organizational business changes through the people, processes, tools and technology involved. The purpose of change management is to support the improvements that TAM introduces.

Managing change ensures that new initiatives introduced to reflect TAM principles are successful, effective, and sustained. Change management guidance can be applied to help advance organizational or process change, as well as systematic or technological implementations and their associated change.

Section 3.4 NEW SECTION

Managing the TAM Workforce

The compounding effects of COVID-19 and the Baby Boomer generation leaving the workforce have contributed to the civilian labor force participation rate dropping to below 62.5% (January 2023) — the lowest rate in 45 years — and presenting challenges for DOTs to find workers. Those who remain active in the labor force have higher expectations of their employers in terms of salaries and working conditions, especially flexibility and the ability to work remotely. At the same time, demands on DOTs for personnel trained in asset management have increased, most recently due to the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), 2021, also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL).

In the past 20 years, DOTs have moved from predominantly performing work themselves to contracting more work to be performed by consultants, with management systems and indicators to guide the work. This shift requires new skill sets, but also presents new opportunities for innovation.

The effective management of a Transportation Asset Management (TAM) workforce is crucial for realizing the benefits of TAM application. This section outlines best practices, strategies, and considerations for developing and sustaining a skilled and efficient TAM workforce.

TIP

An important resource for workforce management is the AASHTO Agency Capability Building Guidance and Portal that was developed through the NCHRP 20-24(95) Ensuring Essential Capability for the Future Transportation Agency project. It provides a library of resources related to transportation agency workforce needs (https://www.agencycapability.com/).

Section 3.5 NEW SECTION

Knowledge Management for TAM

Knowledge management involves the systematic handling of information and resources to effectively support decision-making. This section explores strategies and practices for efficient and effective knowledge management in TAM.

There has been a lot of research related to knowledge management for state departments of transportation. The AASHTO Committee on Knowledge Management website has a wealth of resources for applying knowledge management at transportation agencies.

Establishing TAM Roles, Responsibilities, and Competencies

Identifying a “home” for asset management within the organization is also an important decision agencies need to make. Defining the roles and responsibilities required for asset management is an important step in ensuring a TAM program’s success. Regardless of what organizational model is used to fit asset management within an agency, there are key competencies that should be established as well.

- Chapters

-

Chapter 3

Sections - Chapter 3 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 3

Quick Links

3.1.1

Organizational Models

TAM organizational models help determine where to locate key TAM roles, the relationship between TAM and agency priorities, and how TAM is implemented throughout the agency. There is no one right way to locate and organize asset management within an agency. TAM is cross-cutting by nature and requires coordinated actions across planning, programming, scoping, design, construction, maintenance and operations functions.

Identifying a Home for Asset Management

There are many choices to consider when identifying a "home" for asset management. Asset management committees can be used to achieve coordination across units, regardless of where the TAM home is located, in order to enhance the asset management culture across the organization. Some agencies choose to focus TAM activities within a single business unit and use committees and other management structures to achieve the needed coordination. Others appoint a TAM lead individual to play a coordination role with staff support and resources drawn from multiple units across the agency.

As agencies gain experience with TAM, the organizational model may evolve. At early stages of maturity, an agency may not have any organizational unit or function that is performing TAM activities. In developmental stages of TAM, an agency may create a TAM unit to signal its importance, formalize processes and integrate TAM business practices across the organization. Eventually, as TAM practice is well-established, there may no longer be a need for a TAM unit, because TAM becomes the way the agency does business. Many international agencies with mature TAM practices do not have a TAM unit.

Creating a TAM Unit

An agency can conduct an assessment of where TAM-related functions currently are by making a list of TAM roles and where they exist in the agency. This will determine if there are gaps in needed roles. It will then be necessary to decide whether TAM roles should be added to existing business units, or if it is best to have a TAM unit that performs the roles and responsibilities.

If an agency decides to create a TAM unit, the roles and responsibilities that the unit performs can initially be based on the gap assessment. A beneficial aspect of a TAM unit is that it can focus on specific activities, such as the development and implementation of a federally-compliant TAMP.

Executive Office

Placing a TAM leader or TAM unit in the executive office signals the importance of TAM to the agency and provides a close connection to agency leadership. However, the executive office typically has less direct access to technical staff support than planning or engineering units. Connections to individuals with delivery-oriented responsibilities are also less direct than they would be in an engineering or maintenance office. If the TAM unit is not in the executive office, it’s important that there is an executive involved with the TAM program to both understand how TAM is benefiting the agency and to communicate the importance of TAM to the rest of the agency.

Planning Office

Locating a TAM leader or TAM unit within a planning office establishes a tight connection to long-range planning and, in some agencies, project programming. This fosters a long-term view of asset investments and an integrated approach to meet preservation, safety, mobility and other objectives. However, in many agencies, the planning function is not closely connected to project selection, and may have less engineering expertise. In these agencies, planning has less influence over asset preservation investment decisions.

Engineering Office

Creating a TAM leadership position or TAM unit within an engineering office puts it in proximity to capital design and construction (program delivery) activities. This will tend to give TAM more influence at the agency, as well as access to technical staff resources. Typically, the engineering office takes care of models for asset condition (i.e. pavement and bridge management units), and optimizing asset treatment decision making. However, because of the project delivery focus, there is less connection to long-term planning, systemwide performance, or routine maintenance.

Maintenance and Operations Office

Designating a TAM leader or TAM unit within a maintenance and operations office provides a strong connection to what is happening “on the ground” with respect to asset performance. It also provides an opportunity to emphasize proactive preser¬vation activities to cost-effectively extend the useful life of assets. However, maintenance is rarely involved in long-term planning or capital programming, so the TAM unit may have less influence on overall funding.

The practice examples below illustrate states that have TAM units in the four different agency locations. There is no one right way to locate the lead TAM unit. Figure 3.1, Locating TAM within the Agency, shows where the lead TAM unit is located in 2019 across the US states. The most commonly used location is the planning function.

TAM involves many integrative functions that require collaboration across business units. This map shows the results of an informal survey of the location of the TAM lead within each state department of transportation.

Figure 3.1 Locating TAM within the Agency: An Informal Nationwide Survey

Nationwide Survey

Caltrans

In 2015, the Caltrans Director created a TAM lead in the agency, recognizing the importance of TAM and the necessity of having a TAM lead who is responsible for implementing TAM and meeting federal and state TAM-related requirements. The TAM lead reports directly to the Caltrans Chief Deputy Director. The TAM lead started without any staff, but the unit has grown to house over ten people. The TAM lead is a veteran of the department and is able to advance the TAM program by getting leadership commitment at the executive level and having the business units throughout the department contribute to needed activities.

Caltrans

At Caltrans, the TAM group is in the executive office because of a desire to elevate the importance of asset management. The TAM group has more than 10 people in it who manage the TAMP development, and are also responsible for resource allocation for the State Highway Operation and Protection Program (SHOPP). The SHOPP is a ~$4B annual program for major projects on the California State Highway System (SHS).

Michigan DOT

At Michigan DOT, the asset management function is distributed across the agency, but the TAM lead is in the planning bureau. Locating the TAM lead within planning provides a strong link to strategic investment planning and decision-making.

Connecticut DOT

The Connecticut DOT TAM unit resides in the Bureau of Engineering and Construction and reports directly to the Office of the Chief Engineer. The TAM Unit works with asset stewards, designated for each asset, to coordinate TAM activities across the Department.

Nevada DOT

At the Nevada DOT, the Maintenance and Asset Management Division leads the development of the agency’s Transportation Asset Management Plan (TAMP). The division supports district activities to ensure that the state-maintained highway system is maintained in a condition consistent with the Nevada DOT TAMP, work plans, policies, program objectives, budget, and available resources. It also supports a proactive preservation focus in maintenance that extends to the 10-year investment strategies outlined in the TAMP.

Aligning the TAM Organizational Model with Agency Priorities

The choice of a TAM organization model should align with and support agency policies and priorities. Agencies that have priorities focused on activities that are located in the planning unit (such as economic development, increasing funding, or sustainability) may choose to house TAM in planning. A greater focus on safety and rebuilding infrastructure may lead to locating TAM in engineering. Agencies that prioritize preservation and operations may choose maintenance and operations for the TAM location. Table 3.1 Organizational Models describes how the home for TAM would work in different parts of the agency.

TIP

TAM is not effective unless it is integrated with existing processes. Established agency roles in planning, programming, and delivery can support this integration.

Table 3.1 TAM Organizational Models

Considerations in making the choice on the home for TAM.

TIP

The location of TAM in your agency can evolve over time based on your needs and agency priorities.

Centralized vs. Decentralized Models

A second important choice in creating a TAM organizational model is deciding on the degree to which asset management responsibilities are centralized versus dispersed across the agency.

Model 1. Single TAM Unit

In this model, a central office TAM unit plays a strong role in making decisions and driving TAM actions. Influence is concentrated at a single point, which has advantages, but results in less distributed ownership across the agency.

Model 2. Strong but Distributed Central Office Role

In this model, the central office plays a strong function in investment decisions, but there is no single designated TAM unit. Roles and responsibilities are distributed across multiple central office units and are supported by a central office TAM function that is tied to the investment planning role and may not have a title with TAM in it.

Model 3. Central Office Coordination with Strong Field Office Role

In this model, the central office plays a coordinating role but investment decisions are primarily made by field offices. This approach fosters strong ownership and decision-making that is close to the customer. Establishment of clear guidance and standards at the central office helps to avoid inconsistencies across offices, ensures that a statewide view of asset information can be created, and takes advantage of opportunities to gain efficiencies through the standardization of tools and processes. Field units may take on varying levels of ownership for TAM with respect to data collection, condition and performance monitoring, and work prioritization. The advantage of this model is the stronger link between TAM policies, goals, and objectives and work that is implemented. The disadvantage is the lack of consistent application of TAM across the agency and the greater likelihood that non-TAM priorities are implemented.

TIP

In international agencies, outsourced maintenance is common practice. The integration of TAM objectives in the contracts with the vendors is a important aspect of TAM implementation.

Utah DOT

The TAM unit at UDOT is located in the technology and innovation branch of the agency. This unit is responsible for meeting all TAM-related state and federal requirements and more importantly for advancing TAM and performance management (PM) at the agency. Utah has a strong centralized governance approach to its management so a centralized TAM unit with emphasis on information and innovation works well for advancing TAM.

Oklahoma DOT

The TAM unit at ODOT is in the central office under the planning unit but the implementation of TAM resides in ODOT’s field units called divisions. Most decisions on asset investments and actions occur at the division-level. The central office provides data and guidance to divisions, but decision-making on assets occurs within each division. With the MAP-21/FAST requirements and the need to deliver on the two and four year pavement and bridge targets, ODOT is considering ways to strengthen the central office and division coordination.

New York State DOT

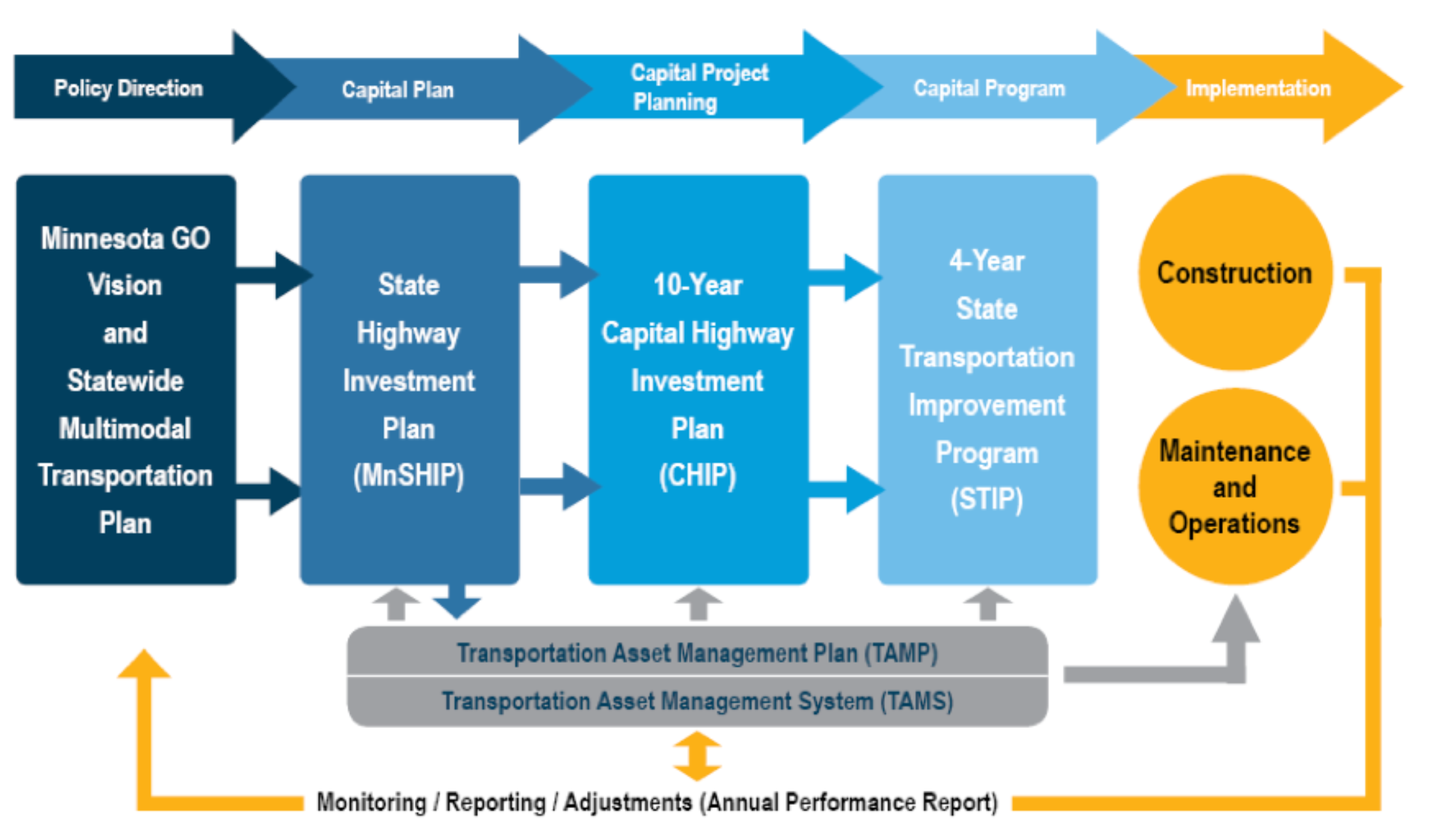

At NYSDOT, Asset Management is coordinated under the Director of Maintenance Program Planning who reports to the Assistant Commissioner for Operations and Asset Management. NYSDOT uses a committee structure, described in their TAMP, to define TAM roles and responsibilities. It has three tiers of related teams: first are the field teams who take action on assets; the next tier are statewide teams located in headquarters that provide a statewide functional team, and the top tier is a comprehensive program team that provides policy and monitoring. A diagram of this is provided in section 3.2.1.

- Chapters

-

Chapter 3

Sections - Chapter 3 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 3

Quick Links

3.1.2

TAM Roles

This section provides information on creating a TAM unit and describes the most common roles needed for a successful TAM program. It also describes TAM related activities within an agency that may require additional coordination. Examples of TAM roles and integrating TAM with other related agency functions are interspersed throughout the section.

Core TAM Roles

Understanding what roles and responsibilities are most important for the TAM program is key to getting an agency ready and aligned to achieve TAM-related goals. It is crucial to fill each TAM-related role with qualified people who possess the right competencies.

Three key roles provide the foundation for implementing TAM in an agency: a TAM champion, a TAM lead, and a lead for each priority asset class.

TAM Champion

Having a TAM program champion leads to greater success in meeting TAM goals and objectives. The TAM champion advocates for TAM advancement and communicates its importance throughout the agency. TAM champions can come from various groups, but they are typically senior managers or executives. The TAM champion should be able to create a vision for how TAM will deliver a stronger agency in the future, communicate how TAM can benefit stakeholders, and gain acceptance from agency staff and stakeholders.

TAM Lead

The TAM lead is the person who is the head of the TAM unit or, if there is no TAM unit, is the lead for coordinating various TAM program activities. People in this role are responsible for making sure agency staff and external partners are working together to advance TAM. The TAM lead should be a person who understands and can manage dependencies across activities and who can develop and maintain good working relationships. The TAM lead should be a constructive problem solver who can monitor the entire program, spot concerns, and listen to and consider alternative points of view when necessary.

An agency’s top management support is an key component of TAM success. One important role of the TAM lead is to keep executive management informed about and engaged in the TAM program. This requires regular and effective communication with executives about plans and achievements. Building executive support for and confidence in TAM activities helps to ensure continued resources and support for TAM activities. When the rest of the agency sees executives supporting the TAM program, they are more likely to assist with TAM needs.

Asset Stewards

Asset stewards (sometimes called “Asset Owners,” “Asset Managers” or simply “Asset Leads”) have lead responsibilities for managing a particular class of asset. This role can be assigned at the agency-wide level as well as at the field office level. An asset steward should be someone who understands the asset well, has the ability to communicate the asset’s needs and the consequences of underinvestment and is able to work with other asset stewards to develop agency-wide investment strategies.

Iowa DOT

When the Iowa DOT TAM program was established, agency leadership prioritized the creation of a world-class asset management program and decided to address TAM implementation as a top-level organizational change initiative. This leadership focus and support allowed Iowa DOT’s TAM team to have authority throughout the agency, address organizational improvement needs, and focus on sustainability by building TAM governance.

TAM-Related Functions: Planning, Programming, and Delivery

TAM is inherently an integrative function, so designation of individuals performing key roles within agency planning, programming and work delivery functions can clarify the key points of responsibility and foster cross-functional coordination.

Project Prioritization

Within each program, key action include:

- Adopting and modifying policies and guidelines for how and when prioritization is done

- Developing prioritization methodologies

- Coordinating the execution of the process

- Gathering and compiling data

- Implementing, managing and updating information systems to support the process

- Performing analysis for individual projects

- Analyzing, reporting and communicating prioritization results

- Making final decisions about which projects will be advanced for funding

Maintenance and Operations

When work is being conducted in the field the following are important considerations for TAM program support:

- Understand TAM goals and objectives and how field actions impact end results.

- Understand the choices that were made during the programming process on asset treatments.

- Capture data on work accomplished to keep asset information accurate.

- Train field staff on the TAM program

Data Collection

Several steps are required to plan and execute data collection efforts – and then to process and store the data that are collected. Some agencies have established roles to provide standardization and coordination across data collection efforts. For each effort, key roles include:

- Analysis to provide a sound business case for data collection

- Research to identify the best method and approach to collecting the data

- Procurement – when contractors are used to collect data

- Data specification and design – that considers integration with existing agency data

- Hardware and software specification and acquisition for data storage and processing

- Guidance and oversight to ensure consistent and valid data

- Data quality assurance

- Data loading and validation

Development of a Long Range Plan

The long-range plan sets the framework for impactful asset investment decisions for the rest of the transportation development process. TAM implementation has a greater impact if TAM roles and responsibilities are clear in this step. It is also important to determine who will take the lead for the following:

- Long range plan policies and priorities related to TAM

- Consideration of tradeoffs across investment types (all program areas and across asset classes)

- Consideration of TAM investment distribution within asset classes (rebuild, rehab, preservation)

- Financial planning (funding outlook across investment types)

Program-Level Budgeting

Allocation of resources across program categories is a critical decision that both enables and constrains what can be accomplished. Where programs are defined based on funding sources or where allocations are based on formulas, there is little or no flexibility. However, where there is flexibility, it is important to establish TAM roles for technical analysis of investment versus performance tradeoffs, as well as for orchestration and facilitation of tradeoff decision making based on the results of this analysis.

Development of the TAMP

TAMP development is a multi-step process that involves agency stakeholders. Clearly articulating process, roles, and lead responsibility for the document yields the best product and makes it easier to implement the TAMP. Table 3.2 illustrates how to provide the link between roles and the key components of a federally-compliant TAMP development process.

TIP

A TAMP cannot be developed in a silo; it required input from across the agency. See Chapter 2 for more information on TAMP development.

Table 3.2 illustrates a way to provide the link between some typical TAM roles and the key components of a federally-compliant TAMP development process.

Table 3.2 - Links to the TAMP Development Process

| TAMP Component | Example TAM Roles and Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Asset Inventory and Condition | Data Collection: State NHS (asset owners); Local NHS (bridges: state bridge unit, pavements: individual local agency data collection units) Data Management: State DOT planning unit collects all data from the various data collection leads Reporting and Visualization: TAMP development team |

| Asset Condition Forecasts | State System Bridges: State bridge management unit runs bridge management system (BMS) Pavements: State pavement management unit runs pavement management system (PMS) Other Assets: No management systems exist for the other assets so each asset owner uses ages to forecast asset condition in the future Non-State NHS Bridges: State bridge management unit runs bridge management system (BMS) and provides forecasts for the entire NHS Pavements: State pavement management unit uses the data collected from local agencies runs pavement management system (PMS) and provides forecasts for the entire NHS |

| Financial Planning | State Funding Forecast: State Chief Financial Officer (CFO) State Funding Uses: TAM unit works with CFO, programming unit, and asset owners to determine uses Non-State NHS: TAM unit works with MPOs and local agencies to determine both funding forecasts and uses of funding |

| Life Cycle Planning and Management | State Assets: TAM unit takes the lead in developing agency wide asset life cycle management policies. Each asset owner uses the agency wide policies and works with the field units to determine asset specific policies. Non-State NHS Assets: Local agencies are invited to a workshop to provide input on life cycle planning and management policies impacting their system. This input is used for development of non-state owned NHS policies. |

| Risk Management | The TAM unit organizes a workshop to develop and refine the risk register and to develop risk mitigation actions. State Assets: Information is used during the programming process to determine funding for risk mitigation actions. Non-state Assets: For non-state NHS bridge and pavement assets, MPOs and local agencies are invited to the risk workshop to participate in the development of the risk register and mitigation actions. Specific funded initiatives are reported by the MPOs and local agencies to the TAM unit for inclusion in the TAMP. |

| Investment Strategies | The TAM unit works with individual asset owners and field units to prioritize investments for TAM improvements, and to meet TAM targets and forecasts. MPOs work with local agencies to develop investment strategies to advance NHS pavement and bridge performance. |

| Process Improvements | The TAM unit uses a workshop to bring together all stakeholders to develop and prioritize TAM improvement initiatives. |

Wyoming DOT

WYDOT is increasing the use of performance-based project selection in order to optimize funding expenditures and meet their performance targets. This process helps guide resource allocation decisions in a constrained funding environment. WYDOT adopted a robust computerized system that moved the agency from project selection predominantly based on emphasizing current condition to project selection based on optimizing future estimated condition. Program managers for each asset type are responsible for maintaining their individual management systems in order to make performance forecasts within their program areas. The TAM lead works with the program managers to get the guidance to the districts. The TAM lead has been working with districts to build confidence in the management system outputs and the decision-process. This improvement has yielded WYDOT’s ability to deliver the targets that they project.

Supporting Roles

The following additional roles are important to support TAM in an agency:

- Asset Data Stewards: ensure all data related to a specific asset class is accurate and aligned with other pieces of data; this is not the same as asset steward/owner.

- Asset Management Software System Owners: manage/own specific software systems, bridge/ pavement management system; the owner is the software owner.

- Asset Management Software System Architects: look at the connectivity of information across systems and across outputs.

- Analysts (data, economics, financial): take data, then apply statistical, economic or financial analysis to provide guidance using that information.

- Maintenance and Operations Managers: are out in a district or field office managing the day-to-day asset activities.

- IT and Data Specialists: usually reside in the Data/IT unit; ensure that overall information and tools support for asset management work.

The following disciplines are key components of a TAM program:

- Engineers: apply understanding of specific asset types, how the condition and role of assets influence treatment choices, and model how investments influence future performance.

- Planners: in the planning or other units; consider long-term planning/policy-making for assets as it relates to programming and the connectivity of information throughout the cycle of activities.

- Economists: look at economic tradeoffs of various scenarios on actions taken for a specific asset.

Table 3.3 - Agency roles list and location

| Executive | Planning | Engineering | Maintenance & Operations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Making | • | • | • | |

| Asset Owner | • | • | • |

|

| Asset Data Steward | • | • | • |

|

| Asset Software | • | • | • |

|

| Asset Engineer | • | • | • |

|

| Economist | • | |||

| Finance/Funding | • | • | ||

| Field Manager | • |

|||

| Communications | • | • | • |

Virginia DOT

The Virginia DOT maintains most of the assets on state roads. For pavements and bridges, there are asset leads at both the central office and in the districts. Asset leads at the central office manage data collection and analysis and provide guidance on the work that is needed. The asset leads in the districts are responsible for implementing the work and recording completed work in the bridge and pavement management systems. The guidance on what work will be done varies by asset class. For overhead sign structures, both the district structure and traffic lead are involved with guidance from the central office traffic engineering division.

Building a Strong TAM Team

Matching TAM Roles to Skills

When TAM is first initiated, roles can be filled with available staff in a manner that takes advantage of available talents and personalities:

- TAM Lead: people-oriented and enthusiastic; able to manage conflict across business units.

- Resource Allocation Leads: analytical and proficient with complex software.

- Data Collection & Management: detail-oriented and accurate.

- Field Maintenance Management: task-oriented monitors.

- Prioritization Leads: comfortable with uncertainty (gray areas), and willing to make decisions.

TIP

TAM is a team effort requiring involvement from analysts, managers, and to executive leaders.

Agencies have different skill needs and capabilities. Some agencies might possess skills ideal for one part of the TAM program, while it might be necessary to look outside the agency (outsource) for other skills. Outsourcing, addressed later on, can be pursued to address a vacancy for a highly qualified position, or to make up for the lack of a specific skillset in the agency.

Making the Case for TAM Positions

Building a case for TAM positions requires defining how the gaps in staffing will hold the agency back from achieving its objectives. If possible, describe the anticipated return on investment from the added staff. It can also be helpful to evaluate TAM efforts at peer agencies, to find out if they have a TAM unit, how many people are in it, and what roles and responsibilities they have. Find examples of agencies that successfully made the case for new staff positions and borrow from their approach.

A Forward-Looking Approach

Part of building a strong TAM team is seeking skills that will help to advance practices rather than sustain the status-quo. Advancements in technology are changing the way data are collected, processed and analyzed; and how work is planned and carried out. As automation increases, certain routine tasks become obsolete, while it becomes necessary to acquire new skills to take advantage of improvements. For example, with tools that produce more robust analysis, agencies will need less people who crunch the numbers but more people to interpret and communicate the results.

Typically, when an agency starts its TAM journey, data accuracy is an issue. When data is not accurate, people may lack the confidence necessary to use the data for making decisions. As data quality and availability improve, the TAM program develops a need for stronger data analytic skills.

As processes become more complex, new skills are needed to monitor and carry out checks and balances. TAM aims to cut across traditional silos, which gets complicated as more units and stakeholders get involved. Therefore, TAM units benefit from people who are comfortable dealing with complex processes. This is a capability that can be acquired through hiring or training.

Utah DOT

The Utah DOT has a strategic initiative to build a learning organization. A key element of this is a learning portal that includes training components. The training components include role expectations, guidance on how to fulfill key responsibilities of the role, and certification information. They have implemented modules for first time supervisors, transportation technicians, stormwater management and advanced leadership with more being developed monthly.

- Chapters

-

Chapter 3

Sections - Chapter 3 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 3

Quick Links

3.1.3

Competencies

Competencies are the combination of knowledge, skills, abilities, and personal attributes that enable individuals or groups to successfully perform their roles and responsibilities. Successful asset management requires a mix of technical and non-technical competencies.

Part of building a strong TAM team is seeking skills that will help to advance practices rather than sustain the status-quo. For example, implementing a TAM program relies on data accuracy and strong data analytic skills. Typically, when an agency starts its TAM journey, data accuracy is an issue. When data is not accurate, people may lack the confidence necessary to use the data for making decisions.

Advancements in technology are changing the way data are collected, processed and analyzed, as well as how work is planned and carried out. As automation increases, certain routine tasks become obsolete, while it becomes necessary to acquire new skills to take advantage of improvements. With tools that produce more robust analysis, agencies will need fewer people who crunch the numbers but more people to interpret and communicate the results. As processes become more complex, new skills are needed to monitor and carry out checks and balances. TAM aims to cut across traditional silos, which gets complicated as more units and stakeholders get involved. Therefore, TAM units benefit from people who are comfortable dealing with complex processes.

TIP

A key requirement under ISO-55001:2014 Asset management is ensuring the organization has identified competencies and is able to demonstrate their staff meets them.

Key Competencies

Part of building a strong TAM team is seeking skills that will help to advance practices rather than sustain the status-quo. For example, implementing a TAM program relies on data accuracy and strong data analytic skills. Typically, when an agency starts its TAM journey, data accuracy is an issue. When data is not accurate, people may lack the confidence necessary to use the data for making decisions.

Advancements in technology are changing the way data are collected, processed and analyzed, as well as how work is planned and carried out. As automation increases, certain routine tasks become obsolete, while it becomes necessary to acquire new skills to take advantage of improvements. With tools that produce more robust analysis, agencies will need fewer people who crunch the numbers but more people to interpret and communicate the results. As processes become more complex, new skills are needed to monitor and carry out checks and balances. TAM aims to cut across traditional silos, which gets complicated as more units and stakeholders get involved. Therefore, TAM units benefit from people who are comfortable dealing with complex processes.

Successful TAM practice relies on a number of key competencies:

Leadership: ability to establish a vision and motivate others to work towards achieving that vision.

Management: ability to make sure that the multiple activities in a TAM program are planned, coordinated, aligned and tracked.

Engineering: ability to understand the fundamentals of transportation asset and system design, construction, maintenance and operation.

Environmental: ability to analyze/ develop prediction models to measure how environmental changes may impact highway infrastructure

Financial planning: ability to understand financial planning basics and an awareness of funding sources and financial tools

Planning: ability to understand a DOT planning process and the constraints of that process.

Strategic planning: ability to understand strategic planning and how TAM fits into an agency’s business activities.

Problem solving: ability to work through inevitable conflicts and issues that arise in the process of working across agency silos.

Relationship building: ability to get different units in an organization to collaborate.

Analytical capabilities: ability to design and apply appropriate methodologies to gain key insights from available information.

Computer know-how: ability to work with a variety of software and comfortably navigate common operating systems.

Data know-how: ability to understand data structures, assemble and manipulate data in a variety of formats, and assess data quality.

Communications: ability to keep communication in forefront of everything that’s done; always aiming to make others understand what TAM program is trying to do. This is important when convincing individuals of change, or helping stakeholders understand TAMP long-term deliverables.

Positive attitude: in large-scale organizational change, taking a positive attitude is crucial to having people accept the change that will help strengthen the program, and convincing them that the solutions are the right ones.

TIP

A job description portal is a part of AASHTO’s Organizational Capabilities Management Portal. This is an excellent tool for sharing TAM job descriptions and competencies information.

FHWA & AASHTO

FHWA, in partnership with AASHTO, has held an annual TAM peer exchange since 2007. These peer exchanges have been a good forum for state DOT representatives to meet each other and hear practices related to the topic of the peer exchange. Peer exchange not only share key ingredients of successful practice – they also discuss challenges and obstacles. The peer exchanges are documented in published reports that are available to the public. A valuable aspect of the peer exchange are the relationships that are formed so that informal exchanges can occur throughout the year.

Developing Competencies within the Organization

TPM Webinar #14 - More Than Just Asphalt, Concrete, and Steel: Innovations from Our People that are Moving Our Transportation System Forward

Peer-to-Peer Learning

TAM knowledge and skills can be gained through experience and peer to peer (P2P) learning. Peer exchanges sponsored by national organizations such as FHWA, FTA, AASHTO, and TRB can be crucial to cross-fertilizing knowledge and experiences. At these peer exchanges, individuals can meet peers and build relationships they can rely on as issues arise in implementing TAM. There are also TAM-related conferences, such as the regularly-held TRB TAM conference. In addition, asset-specific conferences and TAM workshops are held regularly. Many times these events are by invitation, so agencies should contact AASHTO and FHWA to find out about upcoming events.

Competency Assessment & Training Tools

The Institute of Asset Management (IAM) offers an asset management certificate for those who are beginning in TAM roles. The certificate validates a basic understanding of TAM within seven discipline areas and leads to an IAM diploma.

The National Highway Institute (NHI) offers numerous training courses to help build and develop skills in TAM. Some courses are instructor led, while others are web-based. Courses are available for all levels, from those just starting in TAM to those who want to develop greater expertise to help take their TAM programs to the next level of maturity. In addition, transportation professionals can use many of the courses to obtain Continuing Education Units, Certification Maintenance credits, and Professional Development hours. AASHTO and FHWA are continuously developing new capacity-building resources so stay tuned for new training tools.

Information Sharing

When thinking about which competencies are needed in an agency’s TAM program, it is helpful to look at job descriptions for TAM positions in peer agencies. This includes new job descriptions that are developed for emerging roles, such as data scientists. AASHTO is building this capability to share job descriptions. Go to the AASHTO TAM Portal to access this resource.

Consultants

When a TAM unit finds it hard to acquire a core TAM competency, it may be necessary to hire a consultant to fill the need. Consultants can be considered when:

- There is a need to perform a specialized task on a one-time or relatively infrequent basis.

- The types of competencies required are difficult to obtain in the marketplace (e.g. data science)

It is important for agencies to clearly define what they hope to gain from consultants beyond delivery of a report or system. Consultant engagements can be designed to build in knowledge transfer activities to add needed competencies in the agency.

Changing Job Market

In the current robust economy, new employment opportunities make it difficult for state DOTs to attract and retain talent. Developing your TAM organization model to accommodate shorter tenures, incorporate knowledge management, and be clear about the relationship between roles and their impact is important to continued success of the effort.

Finding Talent

Agencies can consider converting existing staff with a planning, financial, or engineering background. Candidates must be results oriented, able to communicate well, possess good presentation skills and be able to bring diverse people together for common goals.

TIP

Existing employees in an agency can be identified to build TAM competency. There are training opportunities in different TAM topics hosted by TAM organizations identified in Chapter 1.

New Mexico DOT

The Capital Program and Investment Director led the NMDOT Asset Management effort and has spent her career in transportation, starting at the FHWA before moving to NMDOT. She has worked in various parts of the NMDOT organization in engineering, administration, and as a district engineer. This variety of experiences gives her the competencies needed to be a successful TAM lead.

Minnesota DOT

The TAM lead at MnDOT came to the role from the maintenance side of the agency. The experience and understanding of maintenance business processes, data needs, and organizational culture help him lead and manage the implementation of TAM processes. Having direct responsibility for budgets and workplans related to maintenance assets, as well as experience in setting statewide performance measures for maintenance services, provided valuable skills and knowledge that now help him to deliver the TAM program at MnDOT.

Connecticut DOT

The CTDOT TAM data lead in the agency started his career in CTDOT’s bridge design unit and moved his interest to the AEC (architecture, engineering, construction) applications area. The competencies he has built in information technology and data combined with his business understanding of transportation assets are important in helping CTDOT’s TAM program roll out tools that support TAM decision-making. The roll out of these tools is in parallel to capital project delivery enhancements that produce continued efficiencies for the entire delivery team.

Strengthening Coordination and Communication

Coordination and communication are key ingredients for TAM success. Many aspects of TAM require alignment across a diverse set of business units and external stakeholders. The goal of coordination and communication is to bring people and groups together to achieve a common set of goals.

- Chapters

-

Chapter 3

Sections - Chapter 3 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 3

Quick Links

3.2.1

Internal Coordination

Different business units in an agency contribute to the TAM process and are crucial to its success. Many TAM activities depend on internal agency coordination, including: drafting TAM policies that impact units throughout the agency; establishing performance targets for asset condition; developing the TAMP; and prioritizing projects and initiatives. The agency’s planning, programming, project development and delivery, maintenance, and other units must coordinate to make TAM work.

TAM-Related Committees

This section touches on the importance of internal coordination committees across the various TAM-related activities. The form of committees is directly related to the agency’s organizational model. These coordination committees are focused on coordination across functions. The coordination committees with important roles in TAM decision-making include:

TAM Steering Committee

This is a senior-level committee made up of top decision-makers. They provide strategic oversight for TAM and facilitate resourcing and organizational support for agreed-upon changes. They also make sure that the politics of any decision are considered. The How-to Guide Establishing a TAM Steering Committee provides steps to set up this function.

Asset Stewards Committee

This is a committee consisting of individuals with accountability for different asset. It provides a forum for getting agreement on standardized approaches, enabling a holistic view of the TAM program, communication about management practices, and discussions about coordinating project development and work planning.

Asset Data Governance Committee

This committee focuses on improving data for TAM. Its activities may include: coordinating asset data collection activities; developing standards to enable integration of data about different assets; monitoring and facilitating adoption of existing standards; establishing data quality management processes; and advancing investments in tools for field data collection, data analysis, reporting and visualization.

TAM Working Group

This group is composed of unit managers across the agency who deal with key aspects of the TAM process – planning, programming, delivery, maintenance, data management, communications, etc.

Coordinating across TAM committees is also an important function. Typically the TAM lead will make sure the activities of various TAM committees are coordinated. In some agencies, the governance across the committees are explicitly stated so that everyone understands who is doing what and how decisions across committees are related.

TIP

Forming a new set of committees to provide TAM coordination is not always the best approach. Some agencies can rely on their existing management structures. Others may already have committees set up to facilitate cross-unit communications. Smaller agencies may be able to rely on informal communication. What is most important is that the TAM program gets the results it seeks.

TIP

When forming a committee, it is important to limit the overall size of the committee to the smallest group needed to accomplish its objectives. Common practice is to limit committees to no more than 12 members.

New Jersey DOT

The New Jersey DOT TAM Steering Committee is comprised of NJDOT senior leadership. The committee sets policy direction and provides executive oversight for the performance management of the state highway system. The Transportation Asset Management Steering Committee provides general direction to the TAMP effort and assists in communicating the purpose and progress to other stakeholders.

New York State DOT

NYSDOT‘s TAM program is made up of a set of teams that perform TAM-related activities. They use TAM as an all encompassing set of principles that are embedded in activities they perform to make and deliver investments that provide mobility and safety to the traveling public. The TAM program coordinates inside the agency to ensure that TAM is being implemented as efficiently and effectively as possible. The following diagram illustrates the inter-relationships and communication that occurs across functional and geographic teams to make TAM work.

Source: Adapted from New York State Transportation Asset Management Plan. 2018.

Ohio DOT

The Ohio DOT Asset Management Leadership Team is a cross-disciplined team, with representatives from all major business units, that establishes data governance and data collection standards. A sub-group of the Leadership Team, the TAM Audit Group, is then responsible for overseeing all asset data related requirements, and making sure standards are in place and processes are followed. This group reviews and approves all data collection efforts and ensures that efforts are coordinated across the DOT. Having designated roles and responsibilities in regards to data governance and collection allows the agency to identify all potential customers of the data being collected and ensure that the data is sufficient to meet all relevant asset management needs.

The Ohio DOT deploys a hierarchy for managing TAM data collection.

- TAM data priority is established by the Governance Board (Assistant Directors)

- The Asset Management Leadership Team (AMLT), which is a cross-discipline team of representatives from all major business units, develop strategies and collaboration opportunities to achieve Governance Board directives

- The TAM Audit Group (TAMAG) perform business relationship management by working with data business owners, SMEs, and stakeholders to create enterprise TAM data requirements

- The Central Office GIS team utilizes the completed TAMAG business requirements to create data collection solutions

- The District TAM Coordinators provide oversight, support and coordination for data collection solution implementation, operations and performance

- Chapters

-

Chapter 3

Sections - Chapter 3 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 3

Quick Links

3.2.2

External Coordination

In order to deliver transportation products and services to the public, State DOTs must coordinate with other agencies that own and operate transportation facilities. Users don’t distinguish who owns what part of the transportation network, so it is up to the agencies to work together and seamlessly deliver the best results to users.

External Entities

Many entities outside of a state DOT are part of the TAM advancement process. It is important to include external partners in TAM committees. For example, many agencies will have a FHWA member on the steering committee, or a governor’s representative on the strategy committee.

Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs)

MPOs carry out transportation planning processes and represent localities in urbanized areas. MPOs are mandated and funded by the federal government and help ensure that transportation planning in the region reflects the needs of the population. MPOs may be responsible for parts of the State’s NHS. It is a federal requirement to involve MPOs when planning or programming federal aid in metropolitan areas, so it is key to coordinate with these organizations when developing the TAMP.

Local Agencies

Local agencies include city and county agencies. These agencies have a stake in asset management initiatives as they often own various parts of the transportation network and have funding for transportation projects. They are also closely connected to the population in the region and thus have an understanding of the needed asset management-related investments.

Other State Agencies

Various aspects of asset management should include other state agencies. State environmental agencies can provide guidance on air quality and emissions. State information systems agencies can be important for obtaining tools or solutions on a TAM need. Statewide data management initiatives may also require close coordination between the state and the DOT.

Toll Authorities

Toll Authorities operate toll roads across the country to generate revenue for use in maintaining the road. Depending on the relationship between the DOT and the authority, the authorities may own the road, have data and information on the condition of the road, and information on the investment in maintenance over time. It is key to coordinate with the authority to obtain a complete picture of the assets in the state.

Other Modal Agencies

Other Modal Agencies include organizations that operate transportation modes that are not directly operated by the state DOT. These might include public transportation, airports, and marine-related functions. The DOT may have a financial relationship with these agencies for grant-related funding. The DOT will also work with these organizations to deliver the best trip for a traveler.

TIP

A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) is an informal agreement on coordination between agencies or other organization. They are effective in clarifying roles and responsibilities between the two agencies and determining how decisions will impact business in the future. For example, informal data agreements often specify who is collecting what, how data is being provided, and what geographic network is included.

Legislative and Oversight Bodies

The governor, transportation commission, and state legislative bodies help determine the funding allocations for each state. It is good practice to coordinate with these entities to ensure they understand the importance of asset management and the need for continued DOT funding.

USDOT and its modal agencies such as FHWA, FTA, and FAA also play a role. The FHWA has state division offices that are the conduit through which states receive federal funding.

Cross-Agency Committees/Councils

Most states have a complex network of agencies that own pieces of the road network in the state. Having a committee or council focused on coordinating TAM policies, pooling resources for tools and methods, and sharing lessons learned can increase the efficient delivery of transportation to customers. This approach can work for geographic regions that cross state boundaries.

General Public

DOTs work with the general public during the planning, programming, and project delivery process. The general public represents the customer that the DOT is ultimately serving with its transportation products and services.

Michigan DOT

One way to coordinate and collaborate across external agencies is to establish a statewide council. Michigan’s Transportation Asset Management Council (TAMC) coordinates TAM at the statewide level. It consists of 10 voting members appointed by the state transportation commission. The transportation asset management council shall include two members from the County Road Association of Michigan, two members from the Michigan Municipal League, two members from the state planning and development regions, one member from the Michigan Townships Association, one member from the Michigan Association of Counties, and two members from the Michigan Department of Transportation. (https://www.michigan.gov/tamc).

In addition, Michigan formed the Michigan Infrastructure Council to: coordinate work beyond transportation assets such as water and communication assets; develop the statewide asset management database, and facilitate the data collection strategy for assets (https://www.michigan.gov/mic/).

Stakeholder Engagement

Stakeholder engagement is another mechanism for coordination. External stakeholders can be partners the agency works with to deliver TAM benefits, and they can also be customers who use the transportation system. Keeping stakeholders informed and engaging them to understand TAM can lead to their support for funding initiatives and their understanding of tough decisions where services may be cut.

Communities of Practice

Communities of Practice (COP) can be used to coordinate with external stakeholders and partners. For example, these communities could be organized across the various asset owners within a region or state to achieve a comprehensive view of TAM. This is a good way to meet MAP-21 requirements and communicate a view of the NHS.

TIP

Public-Private Partnership (P3) Concessionaires are entities that are much more common in international settings. They are not used extensively in the US. When they are involved, it’s important that the performance measures that are being applied to them match the TAM policies and procedures.

New Zealand Transport Agency

Many non-United States organizations have integrated asset management not only within internal organization processes, but also in frameworks that integrate external expertise to assist in infrastructure management. The New Zealand Transport Agency clearly establishes the roles and responsibilities of agency stakeholders and documents the annual transportation planning processes and management practices it employs. This helps the agency manage and deliver the road network, add transparency, and allow resources (other levels of government, consultants, contractors, and other stakeholders including the public) to participate in the process. In this way, it integrates internal and external coordination between stakeholders in the asset management process.

Colorado DOT

The CDOT TAM and Performance Management unit works very closely with the Colorado Transportation Commission, which represents all of the geographic regions in Colorado. Each member of the commission is appointed by the governor and confirmed by the state senate. The commission meetings are open to the public so that all customers of the state’s transportation system are welcome to attend. This promotes participation and transparency between the DOT and its customers. The meeting agenda and materials are available on a website that CDOT manages (https://www.codot.gov/about/transportation-commission/). In the past, the Commission had a designated TAM subcommittee, but due to the priority of TAM, it is now an integral part of the full Commission’s regular business and no longer a subcommittee.

- Chapters

-

Chapter 3

Sections - Chapter 3 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 3

Quick Links

3.2.3

Communication

Strong communication helps TAM implementation programs progress with momentum and helps maintain awareness among all stakeholders. This includes the production and delivery of strong communication products that highlight TAM performance and benefits. An agency should consider a variety of tactics to communicate effectively on all fronts.

Formal and Informal Communications

Agencies with well-planned communication strategies tend to employ a range of techniques to successfully advance TAM awareness and knowledge-sharing. These techniques can be categorized broadly into two groups, formal and informal communications, with distinct characteristics.

Formal communication often provides the stimulus for informal communication. Communication strategies for TAM programs that embed aspects of both types of communication tend to be more successful. Understanding the relative importance of both communication types is important in promoting awareness and knowledge about TAM within an organization.

Utah DOT

When meeting with legislators, the UDOT CEO uses the agency’s Strategic Directions Dashboard on a tablet device to communicate TAM-related information. He is able to quickly respond to questions and show information in a way that is easy to understand. The dashboard shows how UDOT is investing funds allocated by the Utah State Legislature. UDOT has taken advantage of the latest in online technology to provide a live, data- and performance-driven report that is constantly updated to reflect how they are reaching their strategic goals.

Communications Mechanisms

TAM Webinar #37 - Communicating the TAMP and Stakeholder Engagement

Audience-Centric Communication

Holistic communication is about understanding and structuring communication to achieve the best results. This is not always an easy proposition, as effectively communicating a message can be described as changing another person’s perception of an idea. One of the keys to successfully getting desired communication results is knowing the target audience and providing the right communication mechanism.

TAM Communications

Mechanisms

There is a broad range of communication mechanisms available for use, and selecting the right one will increase the likelihood of success. Once the audience is identified it is worthwhile to consider the communication style that the audience would best respond to (verbal, experiential, visual or written), what media or social media platforms they have access to, and whether an interactive environment is appropriate.

TIP

The content of your communication can be just as important as the person delivering the message. Consider how the audience will respond to the messengers selected to deliver the TAM communication.

Table 3.4 - Comparing Formal and Informal Communication

| Basis for Comparison | Formal Communication | Informal Communication |

|---|---|---|

| Meaning | Communication done through predefined channels set by the organization. TAM programs commonly use formal channels for cyclical reporting of performance, or engagement strategies to advance improvement projects. | The interchange of communication stretches in all directions and is uncontrolled. TAM programs commonly create change that manifests informal communication as people are experiencing the change. If managed carefully, it can help advance buy-in and increase the authenticity of program merits. |

| Otherwise known as | Official communication | Grapevine communication |

| Advantages | Timely and systematic flow of information. TAM communication strategies help agencies identify the message, timing and dissemination aspects of formal communication. | Efficient because the information can flow quickly and focus will be personal to the individuals. TAM program champions and advocates need to monitor informal communication and provide feedback to help refine messaging in official channels. |

| Disadvantages | More expensive and challenging to communicate personally to individuals and ensure understanding. More agencies have existing communication resources that can be leveraged. However, some consideration of targeted messaging to TAM stakeholders may require adjustments to existing channels. | Difficult to maintain secrecy and stop misinterpretation. Transparency and consistency in messaging about the TAM programs’ expected benefits and expected implementation timings helps avoid these disadvantages. Should establish feedback mechanisms where there is anticipated risk of resistance to the TAM program. |

| Evidence | Generally written with recorded distribution. This can be useful as a historical timeline, as improvement is tracked over time. TAM implementations take time to make gains. Also good to have a record of past communication that reveals incremental improvement that is not apparent unless assessed over a longer time horizon. | Often no documented evidence of communication. Anonymity can be an advantage to receiving honest feedback about how the TAM program needs to adjust to advance improvement initiatives. Necessary to monitor informal channels to gain insights unavailable in formal channels. |

| TAM Example | TAMP, Data Reporting, Performance Reporting, Program Updates. | Peer-to-peer interactions discussion about progress, informal discussion driven by increased awareness and training. |

TIP

Agencies can choose both formal and informal communication based on the situation Select the best approach for your agency based on your culture and context.

TAM Webinar #25 - TAM Communication

Table 3.5 - Overview of TAM Communication Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Considerations (Pro: +, Con: -) | Internal TAM Examples | External TAM Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reports | + Opportunity to provide detailed information the reader can digest in their own time + Formal communication that is a statement of a position at a defined time. - Can be hard to get feedback | TAMP Annual State of the Infrastructure Report |

|

| Websites, Social media, and Push/Interactive notifications | + Highly interactive + Reaches many people quickly - Feedback is “public” and takes time to manage - Technology may not be accessible to all | Dashboard on internal metrics | Dashboard for performance reporting Consultation and feedback on service delivery |

| Brochures/ Post cards, Newsletters | + Enables simple messages to be clearly communicated + Internal newsletters can be used to inform and engage a broad audience - Can be expensive to produce (in physical form) - Not suitable for getting feedback | Quarterly updates on improvements/ achievements in TAM | Post cards on upcoming asset improvements |

| Presentations, Training | + Opportunity to interact and gather feedback + Opportunity for listeners to learn through experiencing - Requires significant time commitment from participants - Good for a few specific individuals, but challenging to influence more than a few | Formal training Focused status reporting to top management | Community meetings on upcoming asset improvements |

| Videos | + Enables simple messages to be clearly communicated + Can quickly share information to broad audience + Opportunity for leadership to be involved in reinforcing a message - Can be hard to get feedback - Can be time consuming to develop |

TIP

A well-crafted communications plan will empower individuals or units within the agency to communicate. While this may require establishing some standards, limits, or constraints, the focus of the plan should be on providing tools and guidance to promote effective communication.

Region of Waterloo (Ontario)

To assist in the implementation of a new Work Management and Decision Support System, the Region Water Services Division considered decision-making and needs across the organization, and communicated asset management system needs to the Division based around the people that would use the system. The Region created targeted communication tools that reinforced the vision of how asset management might impact people within their various roles in the organization.

By involving people in their current roles as examples, the tools reinforced how asset management frameworks are integrated within their existing work processes and what roles they play within the asset management process. They also highlighted the benefits of the change and how it would impact individuals personally across the organization. As the asset management system evolves through continuous improvement, so too does the need to find effective methods of communication and engagement.

Ohio DOT

Taking Care of What We Have: A message that defines the benefits that TAM brings through tangible examples that are linked to the DOT objectives. Ultimately this inspires confidence in the approach and the TAM decisions being made.

Video: https://youtu.be/B6jZJQBvpc0

Georgia DOT

The Georgia DOT TAMP, published in 2014, included a communication plan to promote awareness of TAM and communicate the benefits of TAM practices. The communication plan highlights the goals and target audiences of communication and includes the key messages that are intended to be conveyed through various means. The main element of the communication plan is a table that lists the audience, communication strategies, and timeframe for the particular strategy. For example, in the near term the agency wants to have one-on-one meetings with members of the State Transportation Board regarding TAM priorities in their respective districts. Finally, the communication plan also contains brief measurement tools to gauge the reach and effectiveness of the communication efforts.

VTrans

Formal and informal communication can travel both upwards and downwards within an organization. Those responsible for TAM at VTrans proactively manage communication where it is practical to do so. When seeking to inform or influence senior leadership, VTrans’ TAM program conveys not only the opportunities and impacts of funding decisions to decision-makers, but also provides context to foster informed choices. The TAM program builds support for the implementation, and elected officials and top management benefit from better context when TAM communication focuses on:

- Understanding current and future performance and how it affects state strategic priorities – How does asset performance influence agency objectives? For example, reducing the amount of bridges with an NBI rating of 1-3 needs to be related back to how freight movement, and economic indicators, can be improved.

- The impact of decisions – What will be achieved with additional/reduced funding or reduced restrictions on expenditure? With the use of life-cycle analysis and reporting of investment strategies, the TAM program can communicate the financial impact of different decision-making.

- The benefit of TAM – Report progress and how program successes are made relevant and advance agency objectives. These benefits are best articulated in terms that are understood by all throughout the organization, e.g. journey time savings/ reliability, and dollars saved. Communication about benefits also can confirm the benefit/implementation of previous decisions, and increase awareness of the success of “we did what we said we would”.

- Continual Improvement – What VTrans’ next TAM improvement will be and the benefit this will provide. Communication like this shows that the TAM program is heading in the right direction rather than continually being told to investigate/consider changes that may distract from strategic pursuits.

VTrans focuses on communication that reinforces confidence in TAM decision-making, to bolster stakeholder belief that the additional dollar invested will be spent in the right place at the right time. The agency also hired a communications consultant to help them develop engaging graphics to communicate critical and complex asset management principles into common, “every-day” storylines and language, transforming their AM approach and their TAMP into a product message that is easy to understand and digest.

Managing Change

In general, TAM implementation or advancement involves introducing organizational business changes through the people, processes, tools and technology involved. The purpose of change management is to support the improvements that TAM introduces.

Managing change ensures that new initiatives introduced to reflect TAM principles are successful, effective, and sustained. Change management guidance can be applied to help advance organizational or process change, as well as systematic or technological implementations and their associated change.

- Chapters

-

Chapter 3

Sections - Chapter 3 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 3

Quick Links

3.3.1

TAM Culture

Working toward widespread acceptance of TAM processes is a culture shift worth pursuing. DOTs are typically known for a “can do” attitude, and that can be powerful in creating the energy needed to make strategic change. An important aspect of culture change is to create open minds that are receptive to TAM advancement initiatives, so the whole agency can embrace them and lead them.

Changing an agency’s culture can have wide¬spread benefits to TAM programs. A culture that fully embraces TAM can make the best use of TAM tools and techniques to further advancement and progress toward maturity. When TAM culture is present and working well, the agency is able to achieve optimal results by working through conflicting perspectives on the key elements of the process.

TAM Change Agents

Making changes is inherent to TAM success. TAM teams need people who will guide and lead the change process. It is important to note that the person making decisions about what changes are needed is not necessarily the one who will carry out the changes. This requires a change agent with the ability to help people understand and adapt to new ways of doing things.

TIP

Implementing TAM or improving TAM business processes involves changing the way the agency conducts business. It involves people, processes, and/or technology. TAM improvement is a change process so it should involve change management techniques.

Minnesota DOT

MnDOT has had a culture of innovation for a long time, and its TAM culture in particular has been advancing. The innovative nature of MnDOT has helped with TAM implementation, but the organization has struggled to fully embrace all of the elements of TAM. The need to institutionalize risk management is an important aspect of MnDOT’s TAM program and progress is being made incrementally. TAM leadership understands that change takes time and they are making progress using a continuous improvement approach.

Colorado DOT

Colorado DOT’s (CDOT) change management program seeks to “help all members of Team CDOT be successful with each and every change which impacts them.” CDOT’s people-centric approach to change management highlights the two-way flow of the information system. Information can flow from project leads, to change agents, to supervisors, and finally to employees. However, information and ideas can also originate with the employees and flow back to the project leads. This encourages engagement from frontline workers. CDOT has identified the following contributors to success in change management:

- Active and visible sponsorship

- Frequent and open communication about the change

- Structured change management approach

- Dedicated change management resources and funding

- Employee engagement and participation

- Engagement with and support from middle management

- Chapters

-

Chapter 3

Sections - Chapter 3 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 3

Quick Links

3.3.2

Understanding the Organization

Transportation agencies must implement changes when adopting new asset management practices at the strategic, tactical and operational levels. TAM programs commonly focus on the changes required and less on how to successfully implement the change. Understanding the potential challenges and learning how to use the agency’s support mechanisms are essential to advancing TAM improvements within the agency.

Building a TAM Organization

Agency leadership and TAM program man¬agement have extra roles to play as communicators, advocates, mentors and change agents. They may require extra tools to help them fulfill their roles, and even to cope with the TAM initiated changes.

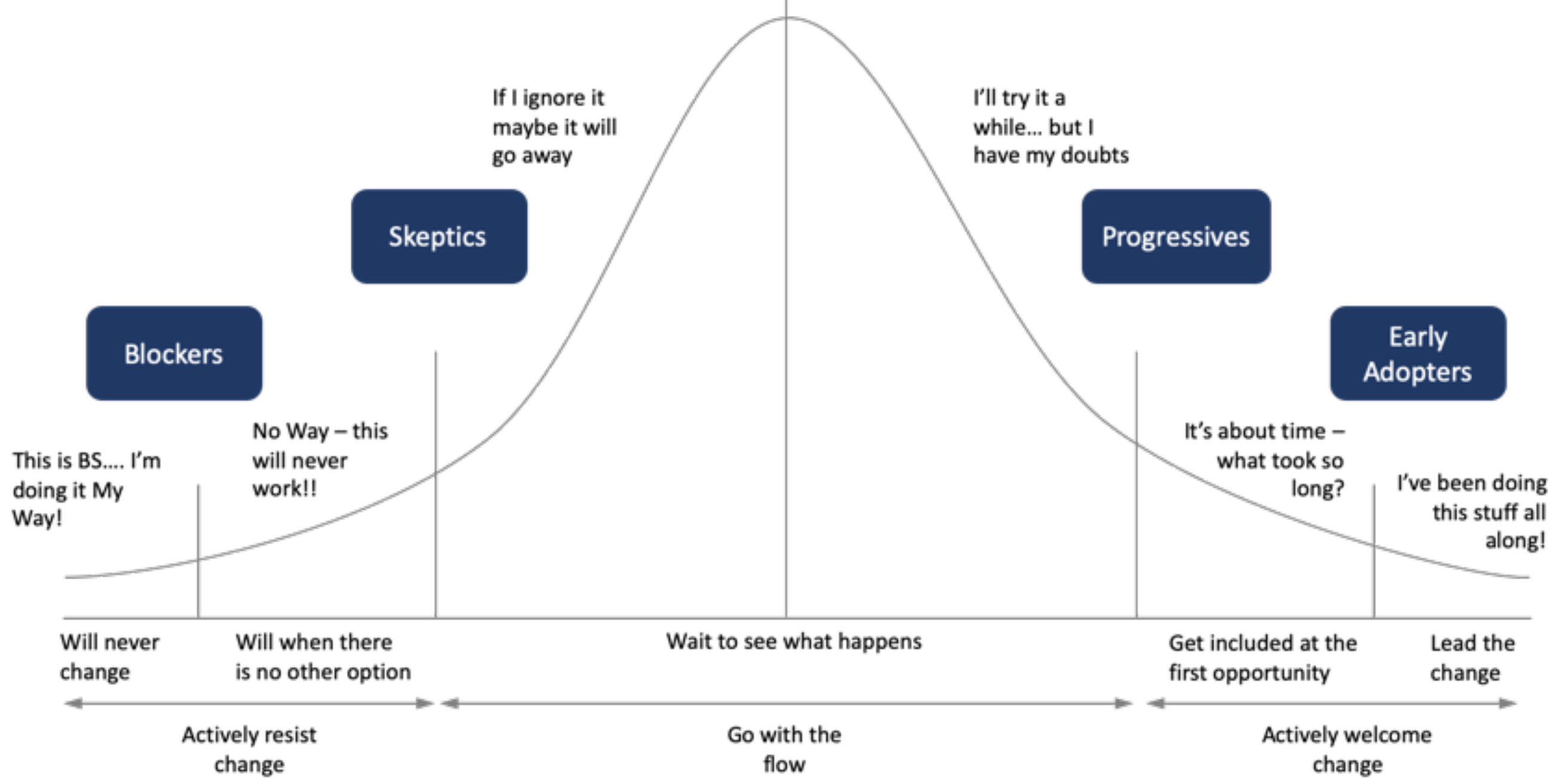

People tend to have similar reactions to any change that will challenge the status quo. Those in favor of the TAM program changes, or those more adaptable to change, may more quickly move through the process of transitioning to new and improved ways of doing things. Figure 3.2, An individual’s response when presented with change, illustrates the range of receptivity to change and how to understand it so that it can be planned for.

TIP

Implementing TAM or improving TAM business processes involves changing the way the agency conducts business. It involves people, processes, and/or technology. TAM improvement is a change process so it should involve change management techniques.

Managers need to be equipped to advance more quickly so they can fulfill their support role successfully, even while they themselves are experiencing the effects of the changes the asset management program is implementing.

Managers need to be equipped to advance more quickly so they can fulfill their support role successfully, even while they themselves are experiencing the effects of the changes the asset management program is implementing.

Asset Management Early Adopters

These are members of the organization who are already prepared to adopt asset management best practices, have been advocating for it in the past and are ready to see the change happen.

What They Need

- Communication channels that are targeted to manage expectations and minimize frustration

- Pilot projects that have good asset data, and can better model and inform tactical and strategic decision-making

- Opportunities to showcase early wins in the TAM transition

Asset Management Progressives

Asset management progressives are predis¬posed to see TAM as a change for the better. They see asset management as a good idea, are willing participants in the change, but need to understand the objectives and what the future will look like.

What They Need