Getting Started with TAM

This page features information curated specifically for those new to asset management. Whether you are new to a transportation agency, recently joined an asset management division, or are a student beginning to learn about topics in asset management, you can to get started right here.

What is TAM?

As defined by the American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO), TAM is a “strategic and systematic process of operating, maintaining, upgrading, and expanding physical assets effectively throughout their life cycle. It focuses on business and engineering practices for resource allocation and utilization, with the objective of better decision making based upon quality information and well defined objectives.”

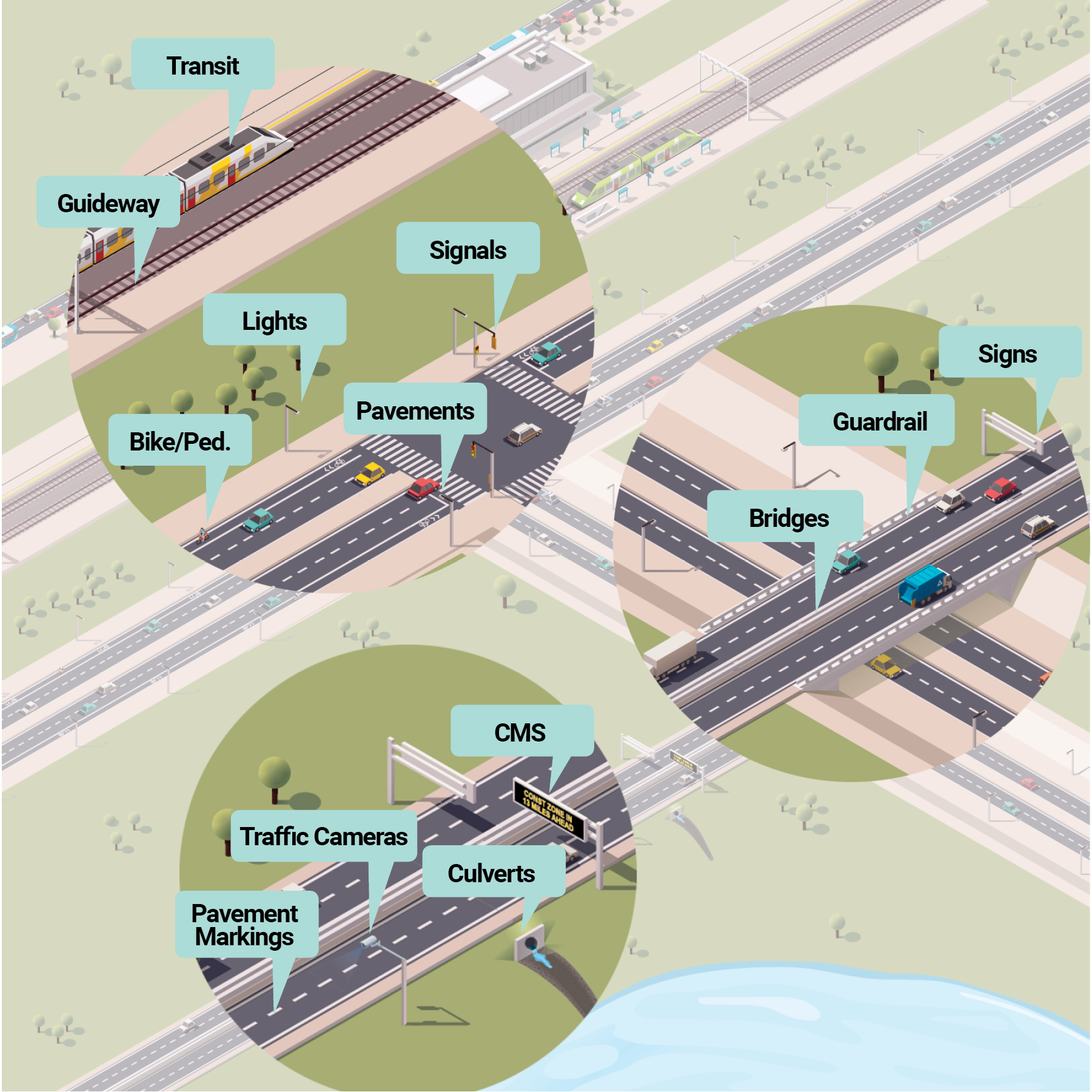

TAM is important because of the size and value of the infrastructure that has been built. The total value of the existing inventory of U.S. transportation assets is staggering; based on data from FHWA Highway Statistics, the replacement value of U.S. bridges and pavement alone is over $5 trillion. TAM offers a set of tools and techniques applicable to sustain the condition and performance of the full range of transportation assets.

TAM has been a focus area for DOTs in the U.S. for over 15 years, paralleling similar efforts to improve asset management in infrastructure-intensive industries in the U.S. and abroad. Over this period, transportation agencies have worked to increase their understanding of the value and performance of existing assets; and implement improved asset management systems and approaches.

This guidance responds to the new challenges that have emerged since TAM was first recognized as a critical area in the U.S. transportation community such as: evolving business practices, technology advancements, constrained funding, changing environment, and legislative requirements.

Video Guides to Transit Asset Management Fundamentals

The following videos have been produced by transportation agencies to communicate what TAM is and why it should be important to a transportation agency.

Why Invest in Asset Management?

An introduction to asset management and explanation for why it is so essential.

Iowa Department of Transportation: TAM Defined

Three-minute video that compares preservation and worst-first approaches to asset management.

An Overview of TAM from the Federal Highway Administration

Eight-minute overview of TAM and its benefits (featuring the original TAM ETG members!)

Definitions

It is important to establish key terms that are used throughout the Guide. While many of these terms have multiple or nuanced definitions, the definitions listed here are the assumed meanings used in the context of this Guide. Each chapter also lists important terms that expand on this list.

Transportation asset management (TAM) is defined by AASHTO as a strategic and systematic process of operating, maintaining, upgrading, and expanding physical assets effectively throughout their life cycle. It focuses on business and engineering practices for resource allocation and utilization, with the objective of better decision making based upon quality information and well defined objectives.

FHWA defines TAM similarly, stating, “Asset management is a strategic and systematic process of operating, maintaining, and improving physical assets, with a focus on engineering and economic analysis based upon quality information, to identify a structured sequence of maintenance, preservation, repair, rehabilitation, and replacement actions that will achieve and sustain a desired state of good repair (SOGR) over the lifecycle of the assets at minimum practicable cost.”

In the International Standards Organization (ISO) Standard 55000, asset management is defined as the “coordinated activity of an organization to realize value from assets. Realization of value involves the balancing of costs, risks, opportunities and performance benefits.” In addition, the ISO standard states that, “Asset management enables an organization to examine the need for, and performance of, assets and asset systems at different levels. Additionally, it enables the application of analytical approaches towards managing an asset over the different stages of its life cycle (which can start with the conception of the need for the asset, through to its disposal, and includes the managing of any potential post disposal liabilities).”

Performance measures are quantifiable metrics that are used to track progress toward goals, objectives, and established performance targets.

A performance target is a level of performance desired to be achieved within a specific time frame.

State of good repair (SGR) refers to a condition in which existing physical assets, both individually and as a system, are functioning as designed within their useful service life and are kept functional through regular maintenance and replacement programs.

Levels of service are an agency’s stated commitment to deliver asset service at a specified level of quality and reliability. Service levels can be asset performance-related or customer/regulatory-related (complaints, meeting regulatory requirements). These levels of service can include, but are not limited to, the historic “level of service” used to grade traffic congestion.

Asset condition refers to an asset’s current state, as specifically defined by its appearance, perceived level of service, and observed physical state, whether or not it impacts its performance.

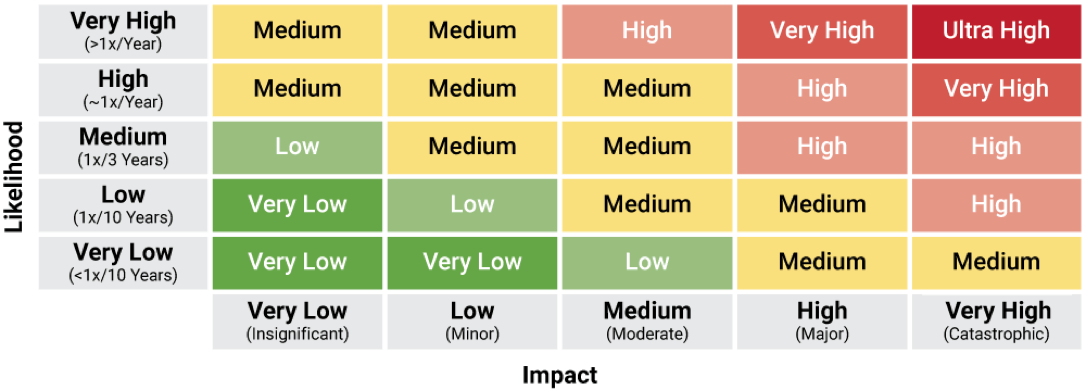

Risk is the positive or negative effect of uncertainty or variability upon agency objectives. [23 USC 515.6]

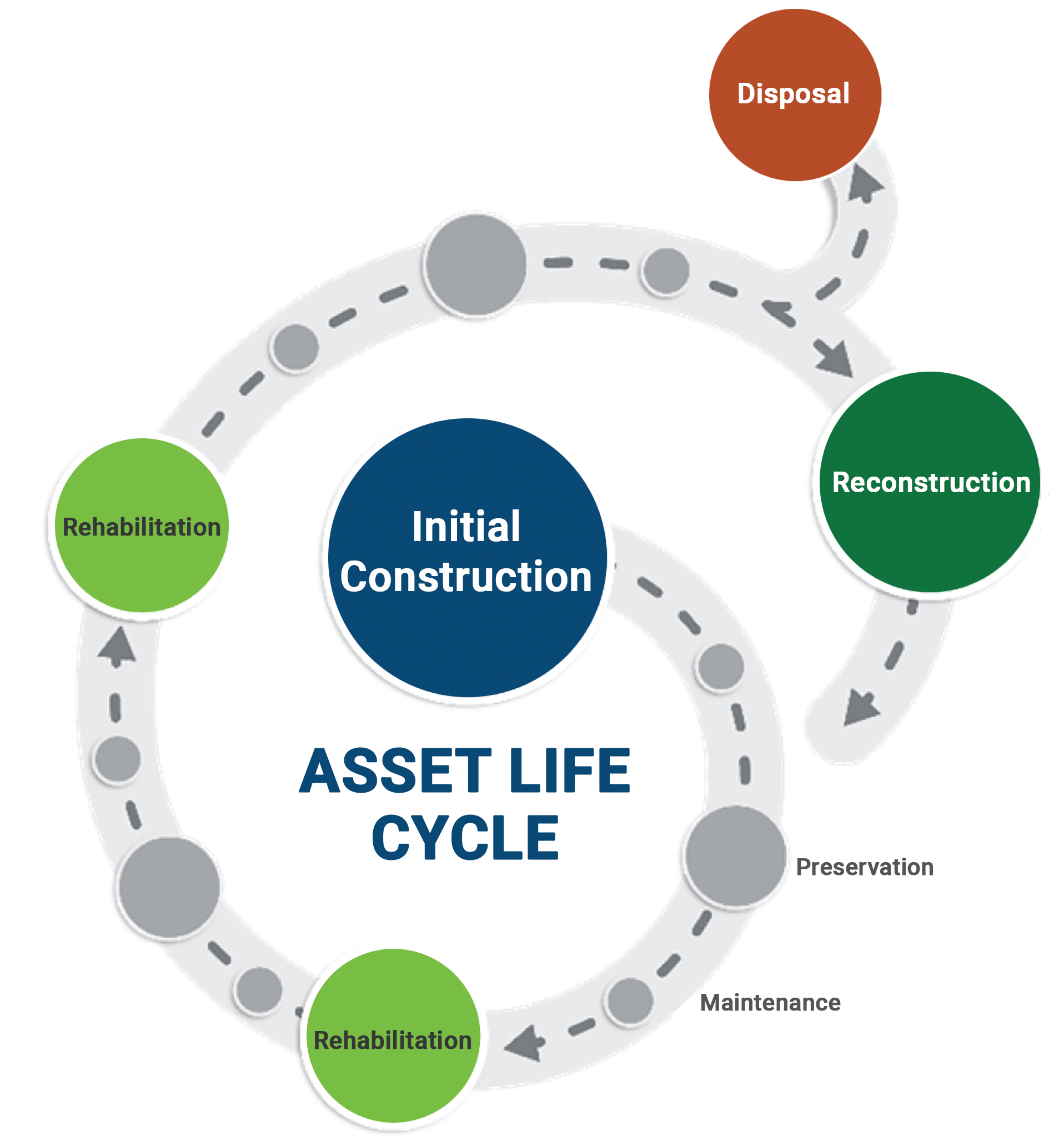

Life cycle planning and management is a process to estimate the cost of managing an asset class, or asset sub-group over its whole life with consideration for minimizing cost while preserving or improving asset condition. [23 CFR 515.5]

Whole-life costing is the systematic consideration of all relevant costs and revenues associated with the development, operations, and maintenance of the asset.

Reliability-centered maintenance is a structured, risk-based approach for determining the maintenance requirement for any physical asset, based on its operating context within the agency.

Resource allocation is the process of assigning scarce resources to investments in transportation assets. The assigned resources can be money, staff time, contractor capacity, equipment, or other organizational requirements for assets. The investments can be capital projects, maintenance efforts, or other projects and activities that require the use of an organization’s resources through various delivery methods.

TAM Principles

The foundation of a good TAM program is a set of principles that establishes the values of the agency and the standards by which the TAM program will be carried out. TAM principles are the underpinnings of all of the activities that will be taken in an agency’s TAM program and connect to its desired end results.

Policy-Driven. TAM should capture and respond to policy objectives, and provide meaningful information about how changes in the transportation system support these objectives. A TAM policy can set boundaries, clarify intent, and communicate the scope of a TAM program including types of assets that will be managed and what work activities to emphasize. [NCHRP 551]

Performance-Based. TAM should have concrete objectives that are translated into system performance measures used for both day-to-day operation and longer-term strategic management. The use of performance data to support the management of assets enables agencies to select and deliver projects that achieve its objectives. Transparent processes allow for accountability to both internal and external stakeholders.

Risk-Based. Risk management plays a role in resource allocation, project selection, long-term planning and other essential parts of the TAM process. As such, an organization’s approach to risk management and the outcomes resulting from a risk assessment have important implications for TAM. An agency must establish a risk management approach and integrate risk management in TAM planning and decision making.

Strategically Aligned with Agency Priorities. TAM measures should be aligned with agency priorities and goals to ensure that investments made to extend asset service life provide the maximum impact to achieve long-term goals. Connecting performance measures to higher level strategic goals also supports an agency’s ability to communicate to customers and stakeholders how technical measures relate to system performance.

Transparent. TAM planning and results should be monitored and reported for both impact and effectiveness. Feedback on actual performance should influence agency goals and objectives, as well as future resource allocation and project decisions. Transparency and agency accountability are key in ensuring the long-term support of project partners, customers and stakeholders.

Information-Driven/Evidence-Based. Strategic decisions with respect to agency goals and TAM objectives should be evaluated using credible and current data. Decision support tools such as management systems should be applied to help in accessing, analyzing and tracking data, and must be an integral part of business and decision processes. Data requirements for performance measures should be realistic and feasible. [NCHRP 551]

Option Oriented. By taking a structured and repeatable approach to TAM decision-making, an organization improves its own resilience and ensures that it will continue to succeed even as new challenges arise and personnel changes over time.

Continuously Improved. TAM processes should provide managers with sufficient information to understand problems and suggest solutions. The agency should be committed to regular, ongoing processes of monitoring and reporting results in order to identify and implement improvements to system performance or further the effectiveness of TAM. [NCHRP 551]

Video Explanation of Asset Management Principles

Principles of Asset Management: Ontario

This video from Ontario, Canada provides an overview of asset management principles.

TAM Elements

Asset management encompasses the full set of business processes related to the management of physical assets. There are several key TAM elements listed below that offer the greatest opportunity to improve an agency's asset management efforts.

TAM Elements Overview

Monitoring the state of the assets and developing desired and expected Levels of Service (LoS). Performance measures are used to align agency investment decisions with organizational objectives, such as asset condition or system reliability, and to monitor progress towards achieving agency goals. In TAM, asset performance is most commonly defined in terms of asset condition or maintenance LoS. LoS provides the link between agency goals and the investments and interventions that should take priority when managing assets.

Maximizing use of available revenues. Agencies are faced with the problem of determining how to divide scarce resources between different asset types, in order to accomplish a variety of different objectives. TAM planning offers processes to help make these resource allocation decisions, such as Multi-Objective Decision Analysis (MODA), long term financial planning, and Life-Cycle Planning.

Monitoring and managing risk. In TAM, uncertainty complicates efforts to make decisions about the future and forces agencies to be nimble so as to effectively respond to unpredictable events and evolving conditions. An organization’s approach to risk management and the outcomes resulting from a risk assessment have implications for TAM. It is important to establish processes to track changes in risks over time and monitor actions taken to manage risks, through tools such as a risk register and/or a risk mitigation plan.

Investing in asset maintenance. State DOTs can specify their desired SGR, consistent with their TAM objectives, for the 10-year analysis period of their TAMP. This strategic long-term maintenance strategy helps agencies minimize the life cycle costs of preserving assets, while also managing asset performance to a defined target to the extent practicable with available resources.

Understanding the potential for asset failure and developing intervention strategies. Being aware of the potential for asset failure and making strategic investment decisions can help agencies prevent failures, reduce costs, and maintain a desired level of service. Over an asset lifecycle, a range of interventions are possible, from reactive, routine and preventative maintenance, to large investment associated with renewal, replacement and disposal.

Allocating resources and prioritizing work based on both short and long-term performance. The resource allocation process should support achieving short- and long-term goals. An agency must establish what scarce resources must be allocated, and what the constraints on these resources are. A key part of the process is to translate goals and objectives into performance measures so the agency can set target values for key measures and/or establish a target level of service.

Continuous improvement based on feedback. An agency should have regular, ongoing processes of monitoring and reporting results in order to identify and implement improvements to system performance or further the effectiveness of the performance management process. Ongoing monitoring, improvement and/or problem identification should be incorporated into the planning process to help adjust and determine future targets and processes.

Aligning the organization. Successful TAM depends on the alignment of a diverse set of internal business units and external partners and stakeholders. Strategic coordination and communication can bring these people and groups together to achieve TAM goals. In addition, the choice of a TAM organization model is important, and should align with and support agency policies and priorities.

Scope and Organization

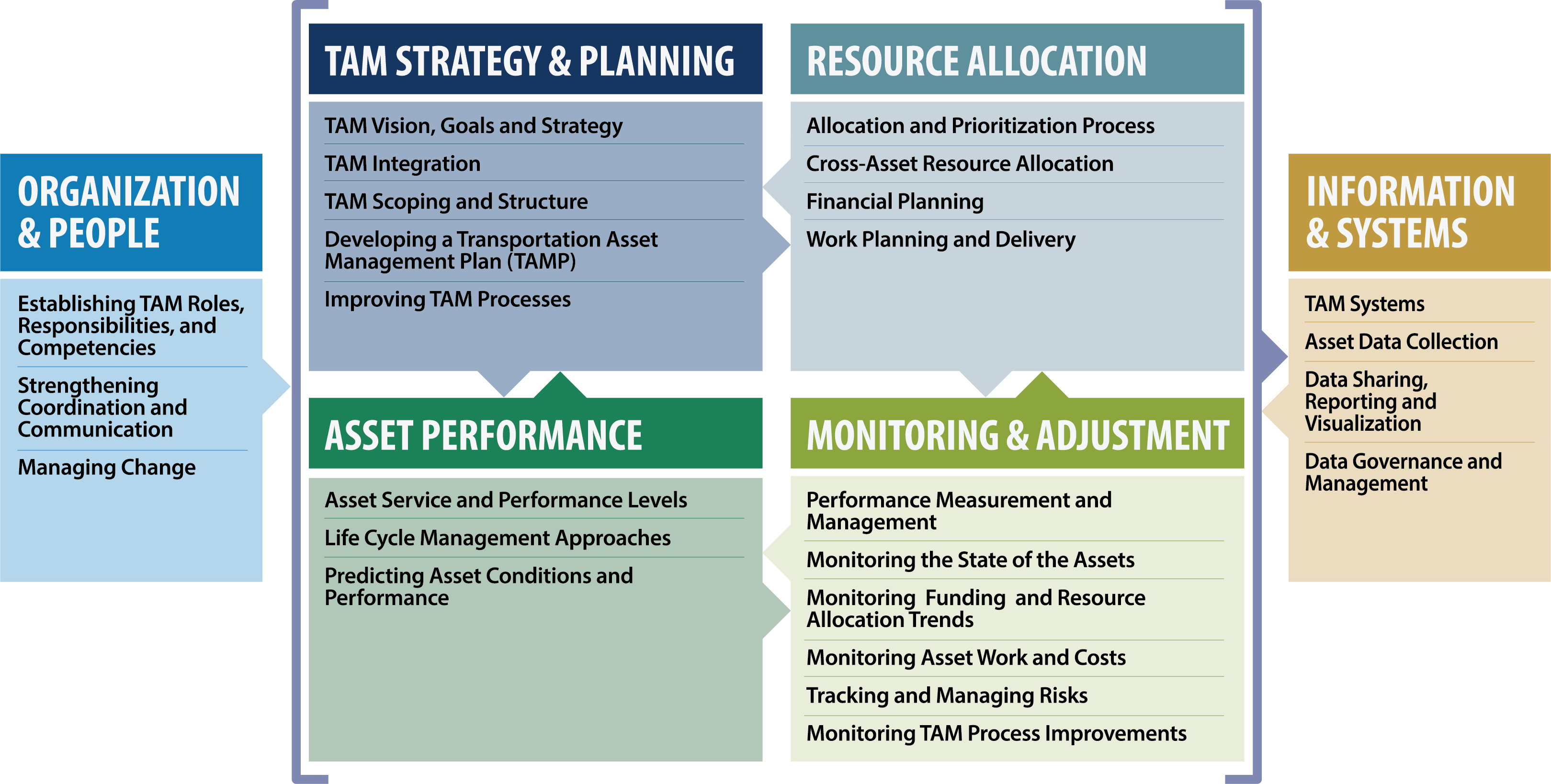

This Guide is organized around the TAM Guide Framework. This framework is tailored for use by U.S. transportation agencies and incorporates critical areas deemed important to the daily application and advancement of TAM practice.

TAM Guide Scope

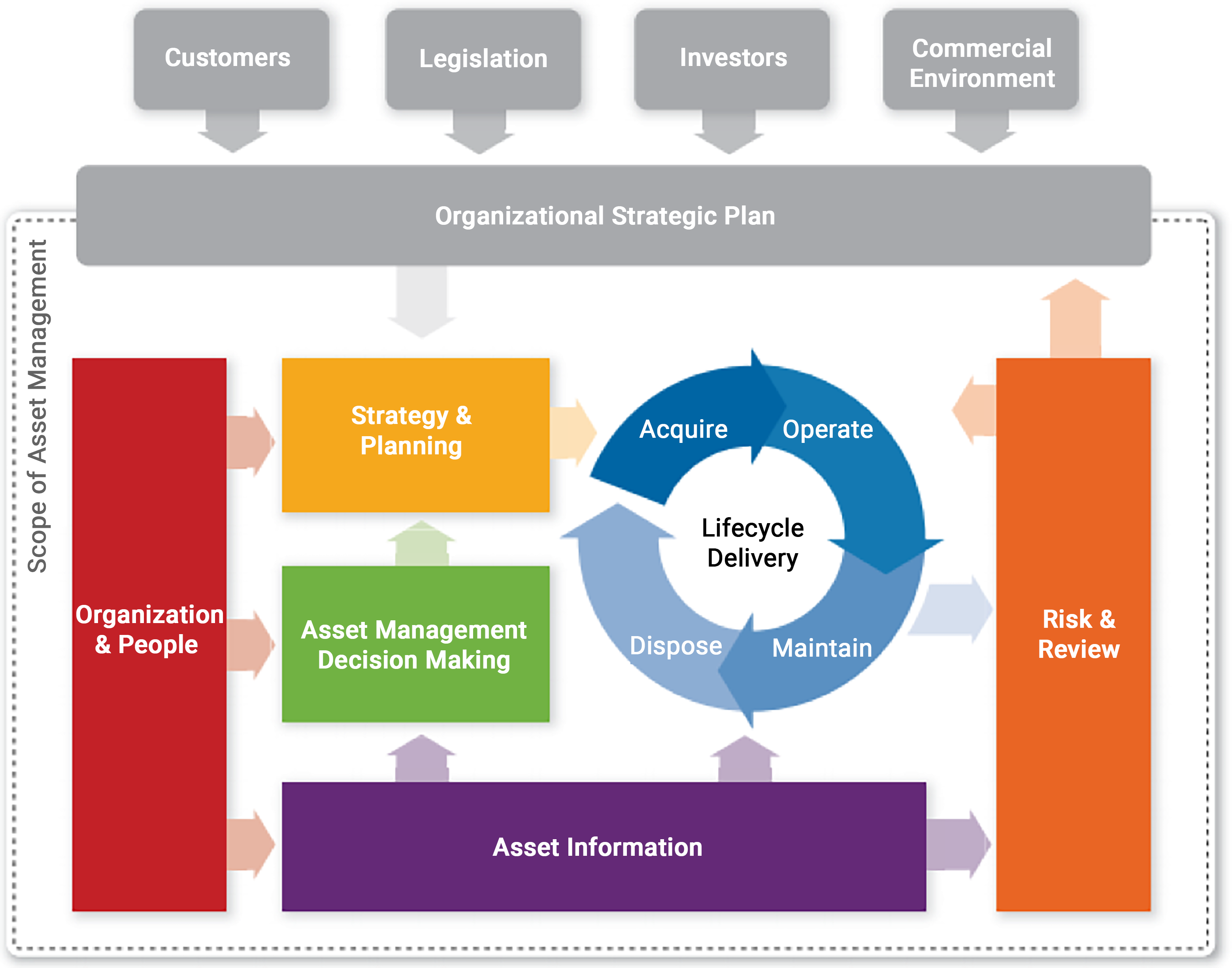

The AASHTO TAM Guide Framework groups the components of asset management into six basic areas. The four central areas in the figure capture the business processes involved in asset management.

TAM Strategy & Planning

An organization manages its assets not as an end in and of itself, but to achieve broader goals. These goals might include improving mobility, enabling economic growth, and reducing costs to travelers and the environment. It is important to place TAM in the context of an agency’s broader goals and objectives, establish the scope of an agency’s TAM effort, and determine how TAM integrates with the other activities performed by the agency. A Transportation Asset Management Plan (TAMP) helps establish this context, and preparing such a document is consistent with best practices in TAM. Additionally, U.S. State transportation departments and transit agencies are now required to develop TAMPs to comply with Federal requirements.

Asset Performance

This encompasses the set of processes involved in determining how to manage an asset over its entire life, from construction or acquisition to maintenance and finally asset replacement or disposal. It addresses how to measure the level of service an asset is achieving and targets to achieve, how to best maintain an asset, and how to model the condition and performance of an asset in the future.

Resource Allocation

Managing assets requires determining how to best deploy a set of fi nite resources, including staff time, equipment, and budgets for operating and capital expenses. This area includes the processes involved in making resource allocation decisions, both for a given asset class, and across multiple asset classes considering a range of different objectives and constraints. Also, it addresses the development of financial plans summarizing expected sources and uses of asset management funds. TAM financial planning takes a long-term view of resource allocation to support the delivery of strategies that address asset needs at all stages of their service lives.

Monitoring and Adjustment

Ideally an organization’s approach to TAM and TAM-related decisions should be dynamic, with adjustments made in response to available data on asset conditions. This area includes processes related to measuring and monitoring asset performance, assessing risk, and making adjustments to investment decisions and business process to respond to changing conditions.

The remaining two areas detail factors that enable an improved asset management approach. The two enablers of an improved asset management approach are:

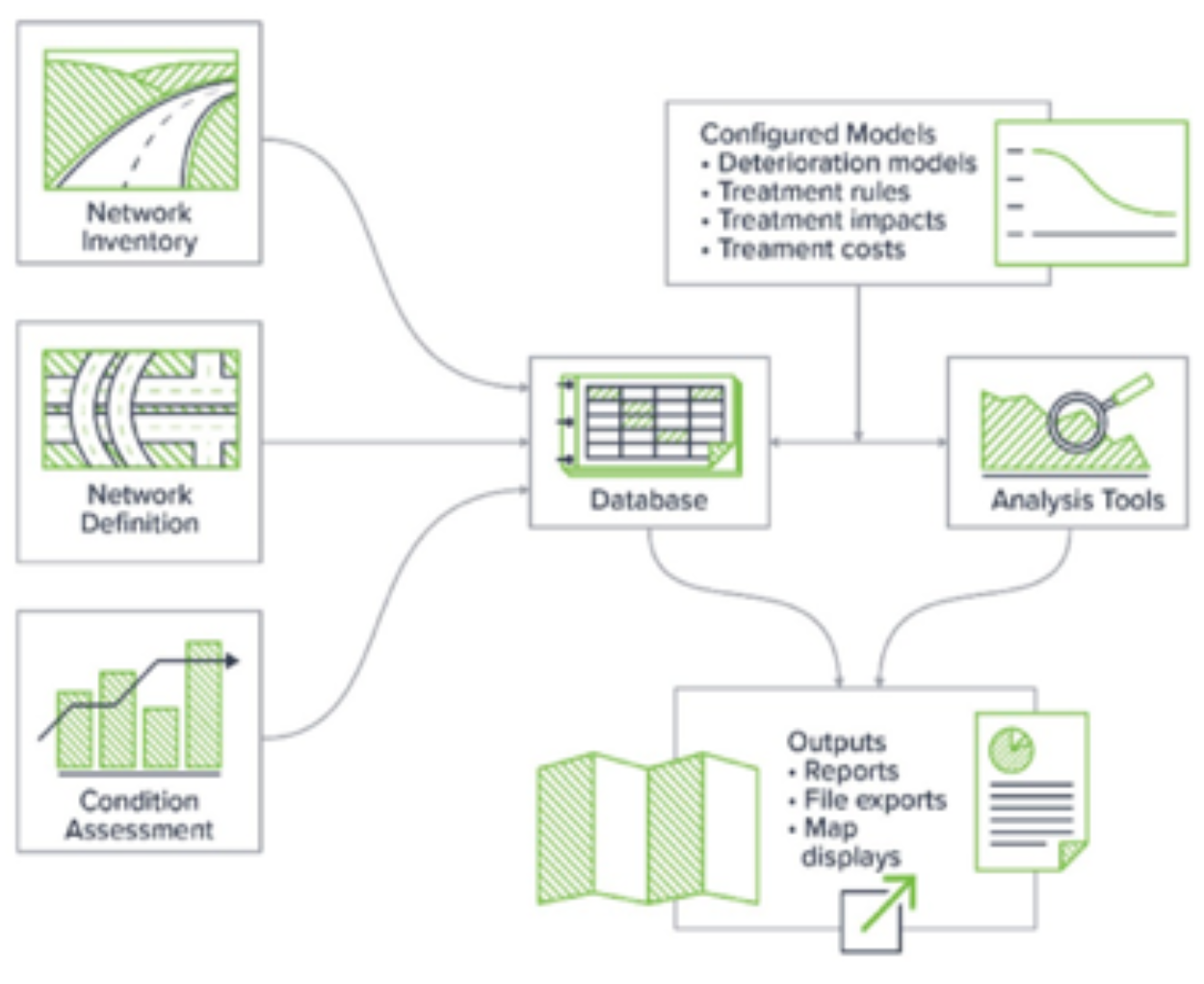

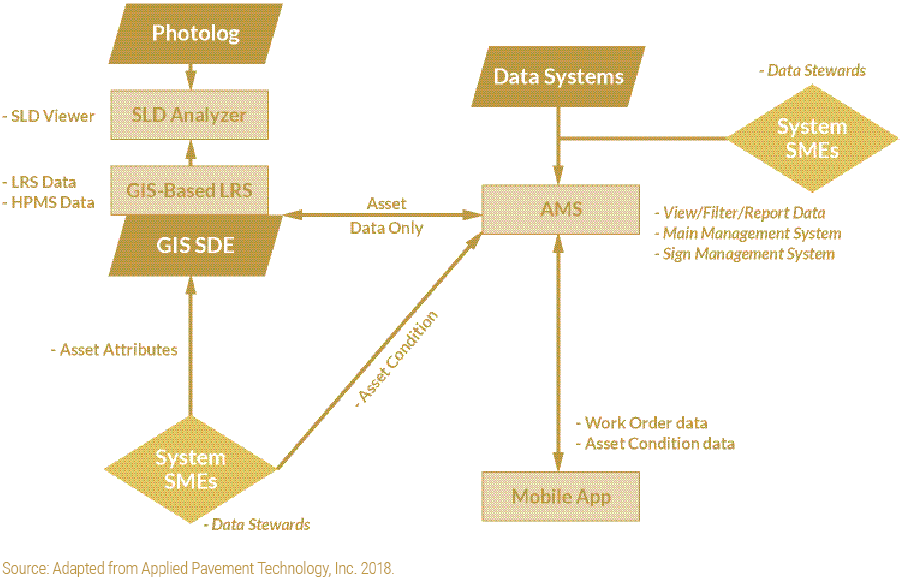

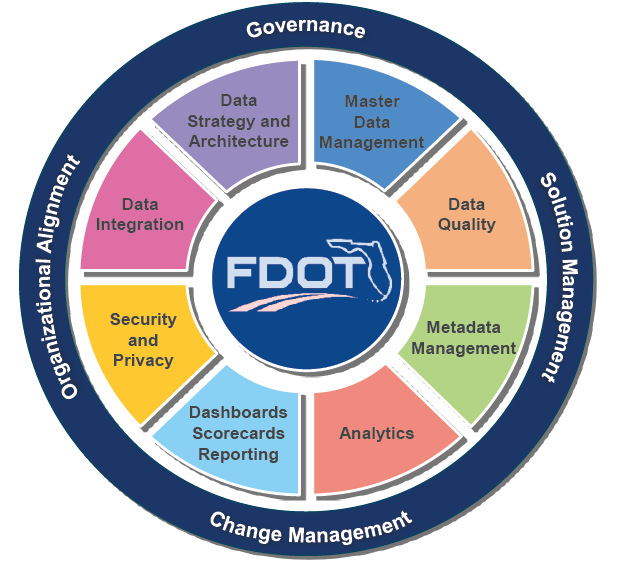

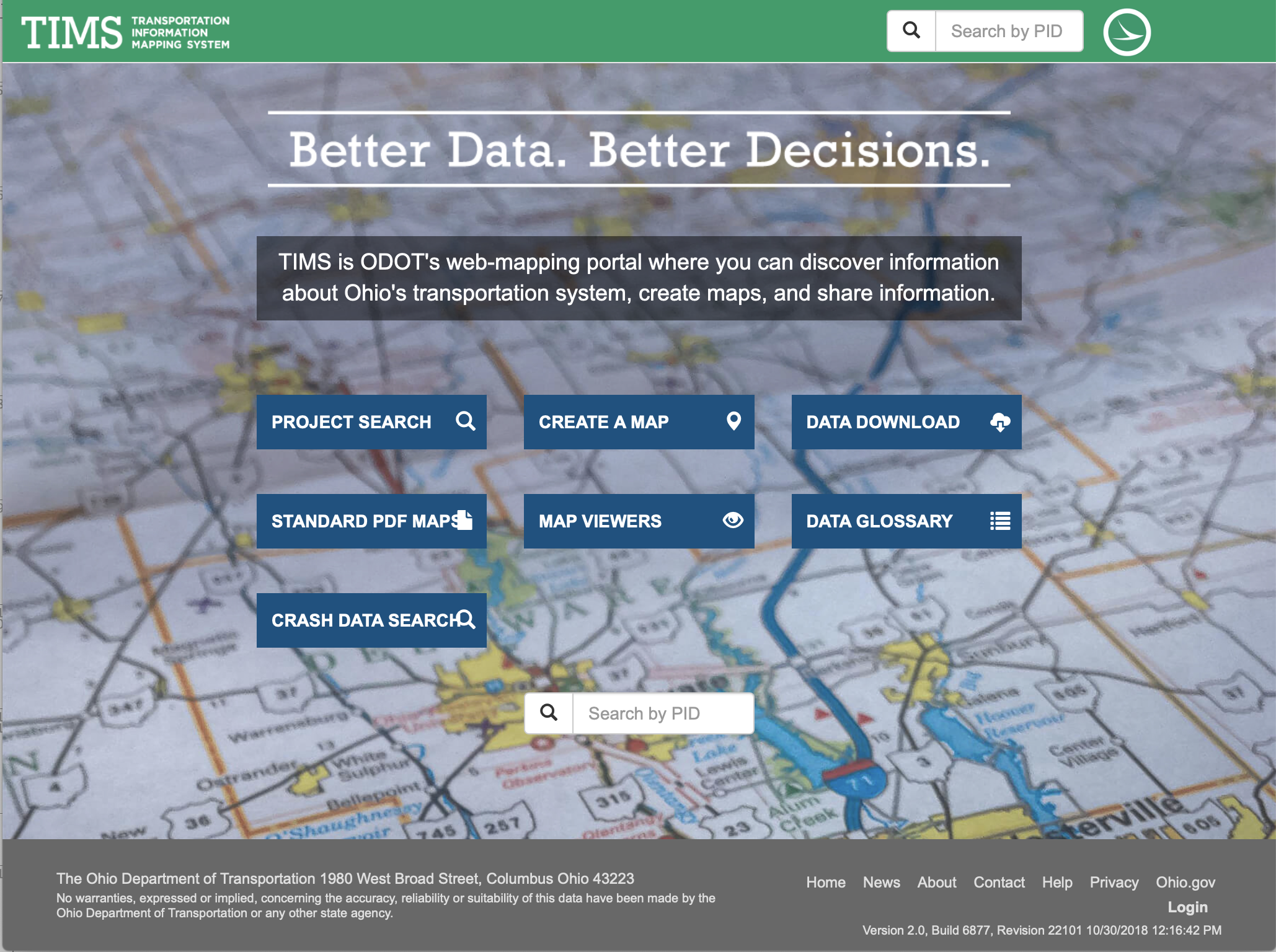

Information & Systems

TAM is very data intensive. It is important to have systems for tracking an organization’s inventory of assets and collecting needed data on asset conditions. Also, systems are often needed to connect to related data, including financial data and records of maintenance work. However, collecting asset data and implementing asset management systems can be costly and time consuming. It is important to develop an approach to information management that carefully considers what data are needed to support the organization’s goals, and how best to collect needed data.

Organization & People

All infrastructure-intensive organizations practice asset management in some manner. However, implementing a robust asset management approach incorporating best industry practices and a philosophy of continuous improvement requires having a robust organization and people with the correct mix of skills. Creating such an organization requires defining roles and responsibilities for TAM within an organization. Also, it is important to evaluate needed staff skills and to implement training programs to help existing staff improve their skillsets. Another important organizational factor is developing an approach for managing change within the organization to support a culture of continuous improvement.

The remainder of this guide further details the areas illustrated in the figure, with emphasis on those areas that are specific to TAM.

A basic feature of TAM is that it is interdisciplinary, and thus overlaps with a number of other areas, including but not limited to maintenance, project selection and budgeting, performance management, information technology, and risk. To the extent that other resources are available for addressing certain aspects of TAM, the text notes these overlaps and recommends other relevant resources.

The core elements illustrated in the TAM Guide Framework are further detailed in corresponding chapters of the Guide:

Chapter 1. TAM Basics discusses basic information of importance to any reader who is new to the concepts of transportation asset management.

Chapter 2. TAM Strategy & Planning discusses considerations in linking asset management to agency goals and objectives, and defining performance measures and targets for tracking progress.

Chapter 3. Asset Performance discusses developing life cycle plans that define how best to design, construct, operate, maintain and dispose of assets - and then executing those plans on a day-to-day basis.

Chapter 4. Resource Allocation details the process of making capital and maintenance investment decisions that provide the best long term performance given available resources, considering trade-offs and competing needs between different assets and investment objectives.

Chapter 5. Monitoring & Adjustment addresses topics including tracking asset health, responding to unplanned events, and managing risks to the asset inventory.

Chapter 6. Information & Systems addresses collecting needed asset data, and implementing management systems to support data collection and decision-making.

Chapter 7. Organization & People describes how to build an organizational structure that supports asset management, and develop processes for change management and training to build an awareness of asset management throughout the organization.

Intended Audiences

The Guide is an important tool that should be actively used as a reference by the transportation community. The principles and implementation techniques described here are universally applicable to all agencies managing transportation assets. While the target audience is primarily State Departments of Transportation (DOTs), local agencies managing metropolitan, county, or mixed transportation networks will also find it useful and appropriate to their needs.

Who Should Use this Guide?

The Guide is structured so that the reader can use a particular chapter, section, or topic as a source of advice; or use the whole in order to drive a systematic agency-wide implementation of asset management.

For those new to asset management who want to learn more. This Guide is a great starting point for DOT staff new to the field of asset management. Recent college graduates and new DOT employees hired in asset management roles, as well as DOT staff who have transferred to an asset management role from elsewhere in the agency will benefit from the overview of asset management provided in this Guide.

For practitioners. This Guide can help advance asset management practice at an agency. The framework is designed to provide information on all different aspects of asset management, so practitioners can easily access information specific to the challenges they are currently facing. Practitioners can also learn about how peer agencies approach different aspects of asset management through the numerous practice examples throughout the Guide.

For executives. This Guide is intended to raise awareness among senior executives about the wider role TAM plays within the agency and how it can be implemented to improve organizational performance and achieve better outcomes in terms of cost and service to the public. Agency-wide TAM implementation needs to be led by top management using the principles of effective leadership. TAM is an organizational culture and professional discipline that should not be switched on and off with the regular election cycle – it needs continuity and support even as leadership within the organization changes. Implementation needs to transcend administration.

Ways to Use this Guide

The Guide provides an overview of TAM topics and also includes practice examples, how-to guides, checklists, and references.

Basic Overview of TAM

A general overview of TAM is provided in Section 1.1. This is a great place for people who are new to asset management to learn the basic fundamentals and benefits of TAM before getting into the details in the remaining chapters.

Topical Guidance

Each chapter of Guide provides topical guidance for the practitioners looking to advance a particular aspect of TAM within their agency. While there are certainly cross-cutting topics in TAM that are mentioned in more than one chapter, each chapter is meant to be a stand-alone topic that a practitioner will find useful without having to read the entire Guide.

How-To Guides and Checklists

Each chapter of the Guide features How-To Guides and Checklists. How-to Guides provide step-by-step guidance on achieving a specific aspect of TAM. Checklists address items that should be place to advance TAM practice in a specific way within an agency.

Maturity Scale

Each chapter concludes with a summary of the typical level of practice of a generic Department of Transportation for three levels of maturity: emerging, strengthening, and advanced. The maturity examples are meant to provide some context for the concepts discussed within the chapter, and the degree to which an agency adopts them in how they conduct service delivery.

Emerging. The agency is beginning to improve their asset management practices and is emerging to a new way of conducting service delivery. The agency has initiated early steps to advance practices and has a plan for future improvements.

Strengthening. The agency has established many aspects of a functioning asset management system, achieved several important improvements in how it embeds asset management leading practice into the agency, and continues to strengthen its practices to achieve future goals.

Advanced. The agency is a role model among its peer agencies and has fully implemented asset management practices across the organization. TAM has become how the agency does business, with a commitment to continuous improvement over time. The agency is advanced relative to most of its peers.

Tips

Where applicable, helpful tips are included in each chapter. These short and practical items help reinforce the concepts discussed in the chapter. They can also indicate key points to remember when applying the guidance

References

At the end of each individual section of the Guide references are provided for more details on specific topics. Practitioners who want to learn more are encouraged to access these references and take advantage of the various resources that are currently available.

Important Tools & Resources

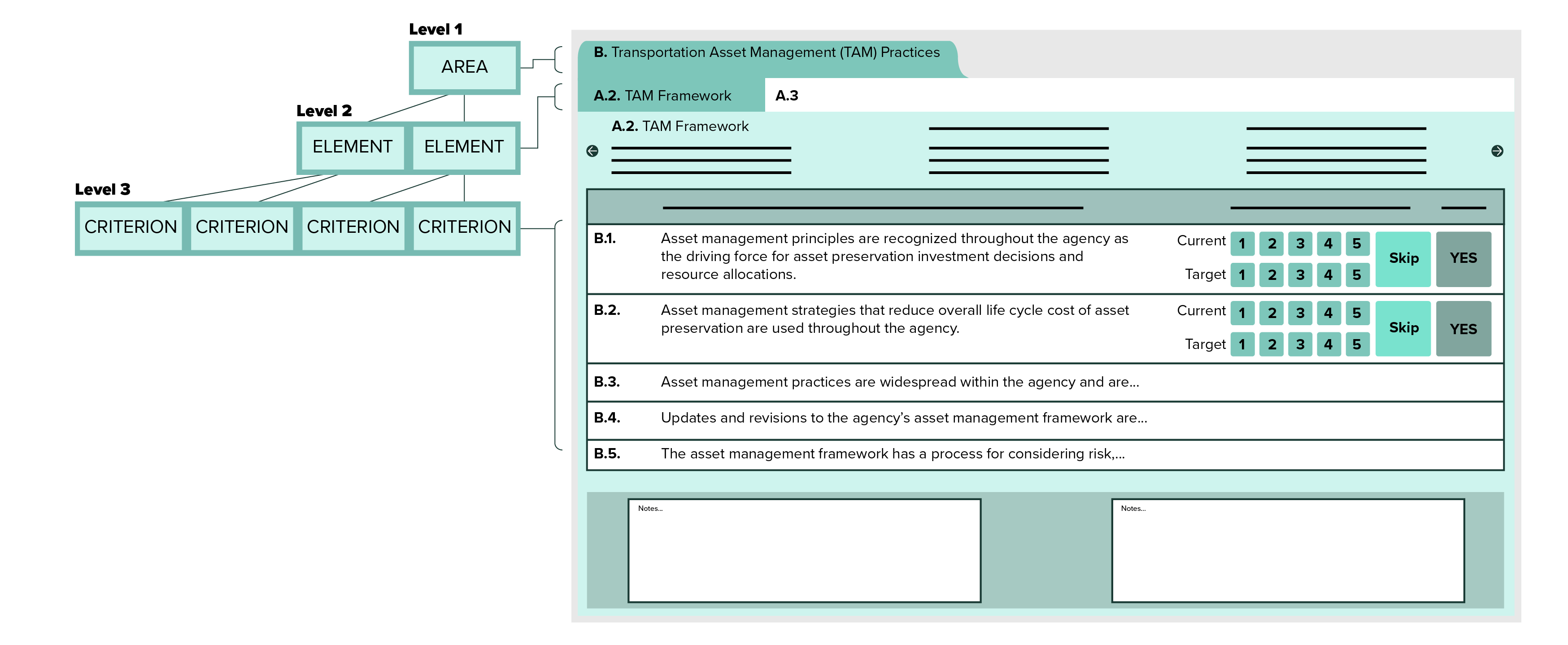

The TAM Gap Analysis Tool is a versatile resource for agencies engaged in Transportation Asset Management (TAM), facilitating systematic self-assessment to identify strengths and weaknesses. Operating at multiple levels, it allows benchmarking against industry standards, pinpointing gaps, and offering flexible result presentations. The tool not only identifies areas for improvement but also provides actionable strategies, making it a valuable asset for agencies seeking to enhance their TAM practices and align with industry benchmarks.

Introducing the TAM Gap Analysis Tool

The TAM Gap Analysis Tool serves as a powerful self-assessment resource for agencies engaged in Transportation Asset Management (TAM). Its primary purpose is to enable agencies to systematically evaluate their TAM practices, offering insights into both strengths and weaknesses. The tool is designed to facilitate this assessment process by allowing agencies to benchmark their practices against established industry standards, identify gaps between current and desired practices, prioritize improvement initiatives, and monitor the evolution of TAM maturity over time. It operates at three distinct levels: Assessment Areas (encompassing topics like Policy goals, Asset Management), Assessment Elements (subcategories within each area), and Assessment Criteria (standards for evaluating practices). The document outlines the specific number of elements and criteria within each of the eight assessment areas, providing a comprehensive framework for evaluation.

A key feature highlighted in the tool is its flexibility, allowing agencies to customize assessments based on participant relevance. The assessment itself is conducted through a user-friendly web-based interface, prompting participants to rate current practices and set desired ratings on a 5-point scale. Results are then compiled into various visual formats such as graphs, spider diagrams, and tables. This provides flexibility for result presentation, offering options at different levels—agency, assessment area, element, or criteria—to cater to diverse reporting needs.

The tool not only assists in identifying gaps but also provides practical guidance on using results to enhance practices. It offers a checklist of strategies tailored to each assessment area, suggesting actionable steps to address identified gaps. Strategies range from aligning agency goals with performance data and developing asset management plans to enhancing communication and outreach and addressing workforce capacity and development. In essence, the TAM Gap Analysis Tool is a versatile resource, empowering agencies to enhance their TAM practices, align with industry benchmarks, and continually improve their capabilities in transportation asset management.

Frameworks and Guidance

There are numerous existing frameworks, models, and guidance documents related to asset management. This Guide is intended to build upon these existing resources and provide updated information where necessary.

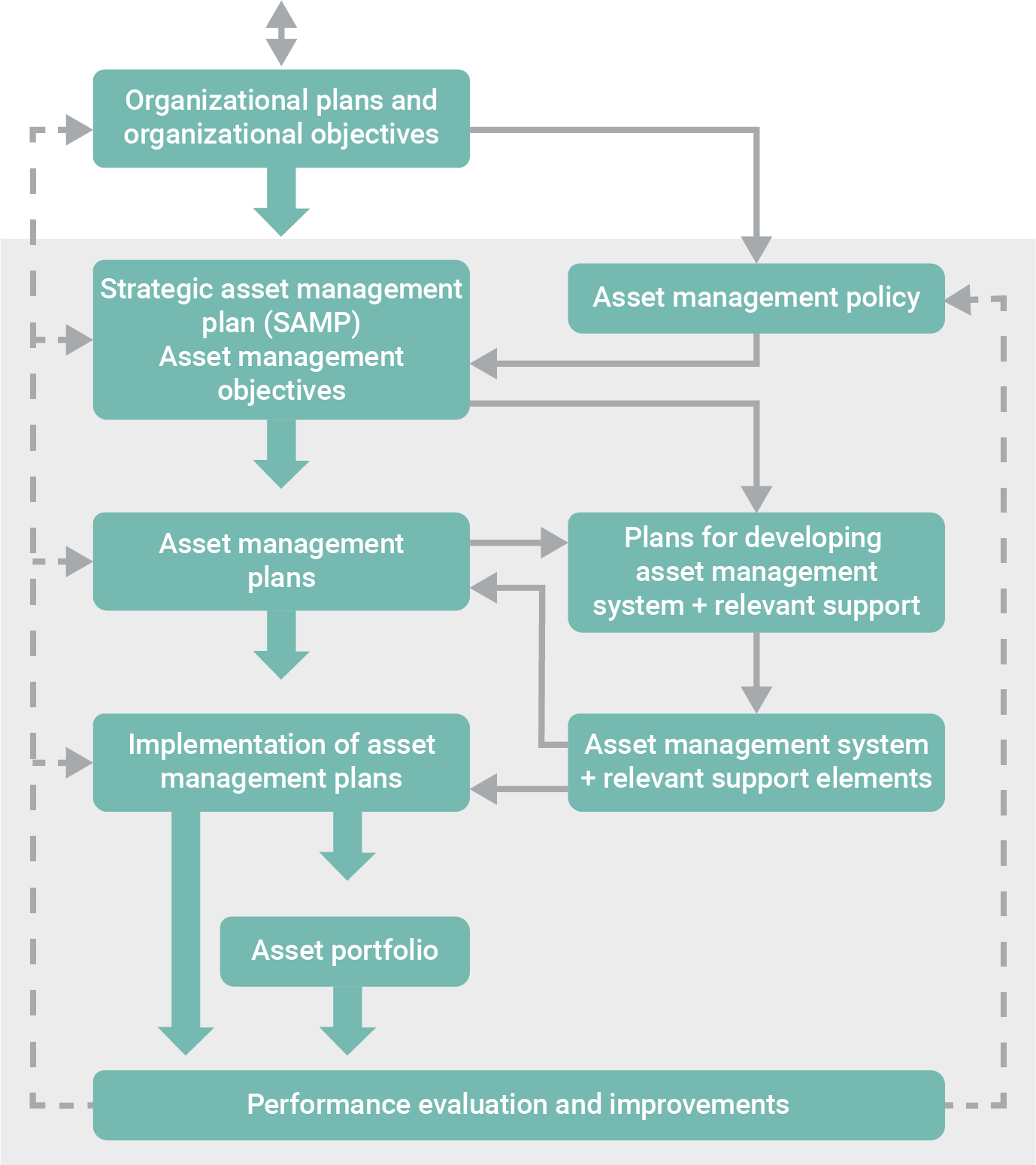

International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

ISO has published a set of standards on asset management. Standard 55000 provides an overview of asset management and asset management systems (i.e. management systems for the management of assets). It also provides the context for ISO 55001 and ISO 55002. International cooperation in the preparation of these standards has identified common practices that can be applied to the broadest range of assets, in the broadest range of organizations, across the broadest range of cultures. The adoption of this International Standard enables an organization to achieve its objectives through the effective and efficient management of its assets. The application of an asset management system provides assurance that those objectives can be achieved consistently and sustainably over time.

Additional standards related to asset management include ISO 55010 which covers guidance on alignment of asset management, finance and accounting; and ISO 55011 which covers guidance on the development of government asset management policy. For more information, the standard is available to purchase: https://www.iso.org/standard/55088.html

Figure 1.3 Relationship between key elements of an asset management program

The gray box designates the boundary of the asset management system

Source: Adapted from ISO 55000. 2016

Publicly Available Standard (PAS) 55

Prior to the development of ISO 55000, the Publicly Available Standard (PAS) 55 was released by the British Standards Institute. This standard contains terms and definitions; information on asset management policy, strategy, and objectives; discussion on implementing asset management plans; as well as performance assessment and improvement information. The standard is available to purchase: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:55000:ed-1:v2:en.

Figure 1.4 Planning and Implementation Elements of an Asset Management System

Source: Adapted from PAS 55

Institute of Asset Management (IAM)

The IAM publication, Asset Management – An Anatomy (2015), provides a basic overview of asset management and its benefits. It also provides a discussion of six asset management subject areas: Strategy and Planning, Asset Management Decision-Making, Life Cycle Delivery, Asset Information, Organization and People, and Risk and Review. These subject areas are reflected in the framework shown in Figure 1.5.

IAM also has information on developing and maintaining a Strategic Asset Management Plan (SAMP). All of their resources can be found on their website: https://theiam.org/.

Figure 1.5 Planning and implementation elements of an asset management system

Source: Adapted from PAS 55

Institute of Public Work Engineering Australasia (IPWEA)

Institute of Public Work Engineering Australasia (IPWEA) IPWEA has produced the International Infrastructure Management Manual (IIMM). This guide provides checklists, process, guidance, and case studies on asset management practice from agencies globally. The manual contains guidance for all infrastructure types and is suitable for agencies of all levels of maturity. The manual is written to align with ISO 55000 with a focus on how to implement asset management concepts.

The IIMM must be purchased from the IPWEA online bookshop which can be accessed here: https://www.ipwea.org/resourcesnew/bookshop/iimm.

UK Road Liaison Group

The UK Road Liaison Group developed the publication titled Well-Managed Highway Infrastructure: A Code of Practice. This code is designed to support and promote the adoption of an integrated asset management approach to highway infrastructure based on the establishment of levels of service through risk based assessment. The code is broken into four sections: Overarching Principles, Highways, Structures, and Lighting. The Code also summarizes 36 recommendations put forward to the Department for Transport to enhance asset management across UK highway networks.

A PDF of this document is available online: http://www.ukroadsliaisongroup.org/en/utilities/document-summary.cfm?docid=4F93BA10-D3B0-4222-827A8C48401B26AC.

Legislation and Regulations

The federal government recognizes the importance of asset management practice and requires states to develop transportation asset management plans. Many state governments also have implemented laws related to asset management.

Federal Legislation

The transportation authorization legislation Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century (MAP-21) signed into law in 2012 includes a number of provisions related to asset management and performance management for both highway and transit modes. The requirements established in MAP-21 were continued in the subsequent legislation Fixing America First Act (FAST) signed into law in 2015. For the highway mode MAP-21 defines asset management in the context of transportation and requires that State DOTs develop risk-based transportation asset management plans (TAMPs) for assets on the National Highway System (NHS). The law also includes a number of requirements related to performance management. Regarding transit MAP-21 requires that U.S. transit agencies develop TAMPs that detail asset conditions and include a prioritized list of state of good repair (SGR) investments.

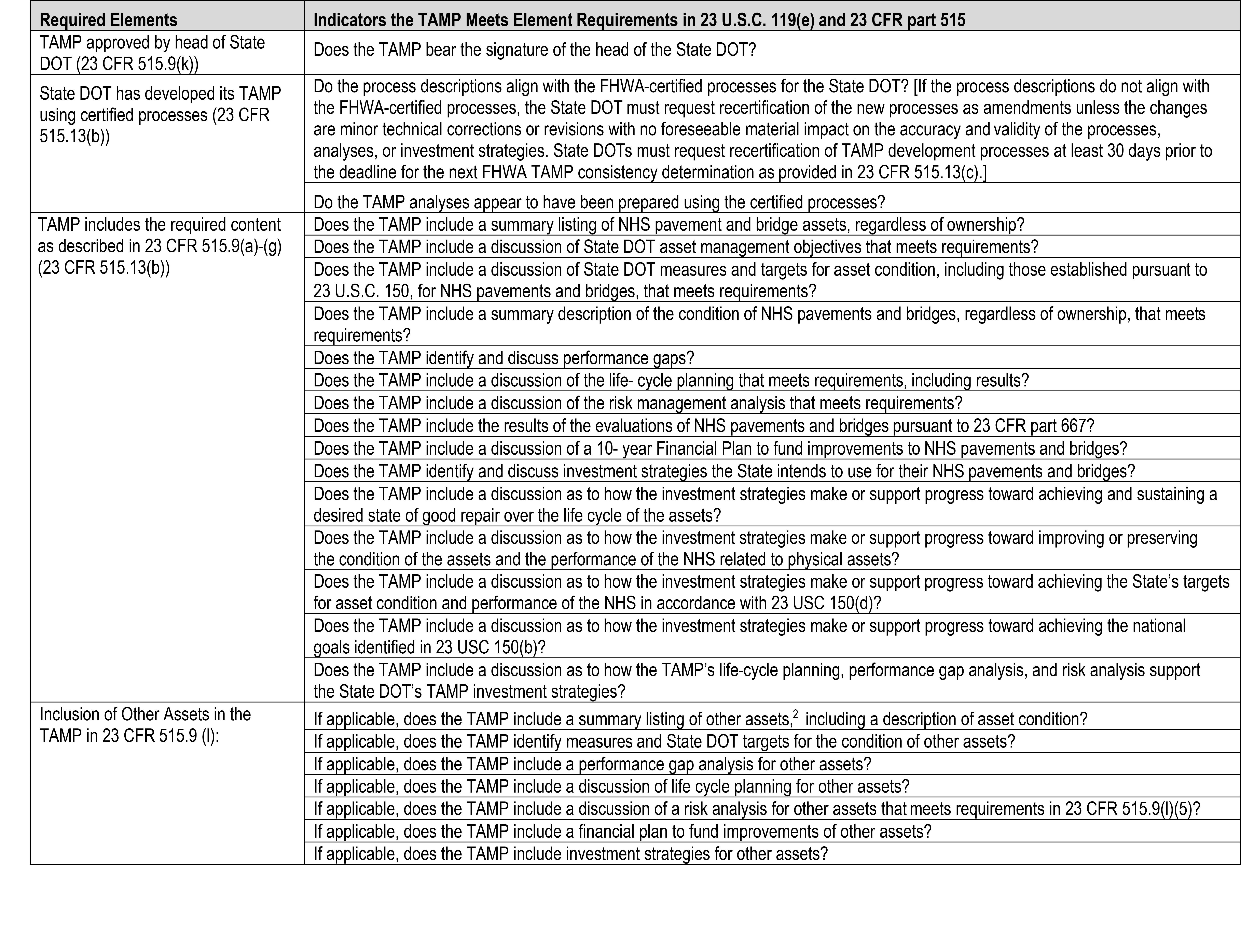

Following passage of MAP-21 and FAST the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA) developed rules detailing the TAM requirements for highways and transit, respectively. In 2016 FHWA finalized § 23 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 515 – Asset Management Plans. FHWA’s requirements specify that a TAMP should detail asset inventory, current conditions, and predicted future conditions over a 10-year period, using performance measures detailed in FHWA’s performance management regulations. The TAMP should include the following elements:

- Asset Management Objectives

- Asset Management Measures and Targets

- Inventory and Conditions

- Performance Gap Identification

- Life-Cycle Planning

- Risk Management Analysis

- Financial Plan

- Investment Strategies

In 2016, the FTA finalized asset management requirements U.S. transit agencies must follow. These requirements are detailed in §49 CFR Parts 625 and 630. The FTA requirements detail that transit agencies must prepare TAMPs covering a four-year period and including their revenue vehicles, infrastructure, facilities, and equipment (including service vehicles). Agencies must use a decision support tool to help analyze SGR investment needs and develop a prioritized list of needs. Larger agencies (with rail systems and/or 100 or more vehicles in peak revenue service) must include additional materials in their TAMP, such as a TAM/SGR policy, TAM implementation strategy, evaluation plan, and identification of resources required to implement the plan.

TAM Webinar #52 – The IIJA and TPM

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act/Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (IIJA/BIL) that took effect on October 1, 2021 required State DOTs to consider extreme weather and resilience as part of the life-cycle planning and risk management analyses within a State TAMP. This means that state DOTs must take into account the potential for extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, floods, and wildfires, when making decisions about how to maintain and invest in their transportation infrastructure. This change is important because it will better inform the decision-making of State DOTs and other Federal-aid recipients who ultimately select projects in which to invest federal-aid dollars to improve the resilience of the surface transportation network. These updates were first required in 2022 as State DOT updated their TAMP development processes and TAMPs based on the 4-year cycle in Title 23, Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Part 515.13(c).

The IIJA/BIL also provides funding for a number of new programs that are relevant to transportation asset management, such as the Bridge Investment Program and the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program. These programs can help state DOTs to make necessary repairs and upgrades to their transportation infrastructure, and to invest in new technologies that can make their transportation systems more sustainable and resilient.

In addition, the IIJA/BIL includes a number of provisions that are designed to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of state DOT transportation asset management programs. These provisions include requirements for state DOTs to develop and implement asset management plans, to collect and use data to inform their asset management decisions, and to collaborate with other stakeholders on asset management issues.

TAM Webinar #44 - TAMP and STIP Integration

The most recent information on federal requirements and regulations are available at the following:

FHWA Transportation Asset Management: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/asset/

FTA Transit Asset Management: https://www.transit.dot.gov/TAM

Assessment Tools and Maturity Models

Assessing asset management maturity helps establish goals and encourages improvement. This section provides information on existing assessment tools and maturity models agencies can use as resources.

TAM Gap Analysis Tool

This Excel-based gap analysis tool was developed under National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Project 08-90 and builds on the gap analysis tool introduced in the AASHTO Transportation Asset Management Guide – A Focus on Implementation. The tool helps agencies identify and prioritize needed enhancements to their asset management programs.

In 2023, the TAM Gap Analysis Tool was reproduced as a web-based tool, providing enhanced functionality and a streamlined user experience, resolving software compatibility issues that had developed in the 2014 excel-based version, and updating the assessment framework to better reflect current practices. More information on the TAM Gap Analysis Tool is provided in section 1.4, TAM Gap Analysis Tool Overview. The new version of the tool and the User’s Guide are available on the AASHTO TAM Portal: https://www.tam-portal.com/resource-set/tam-gap-analysis-tool-nchrp-08-90/

TAM Webinar #57 - TAM Tools Miniseries 04: Techniques

IAM Maturity Scale and Guidance

The IAM Maturity Scale and Guidance document provides a generic maturity scale for agencies looking to assess their current asset management practice and determine ways to grow and mature. This guidance is available for purchase here: https://theiam.org/asset-management-maturity-scale-and-guidance-pdf/.

Data Gap Assessment Tool

To assess data and information maturity, agencies can use NCHRP Report 814, Data to Support Transportation Agency Business Needs: A Self-Assessment Guide. This report provides steps to prepare for the assessment, conduct the assessment, and improve and monitor the agency’s data and information maturity over time. The assessment approach presented is flexible and scalable to many different agency needs. The Guide helps agencies determine if they have the right data, if their data is good enough, if they are getting full value from their data, and what they need to do to improve.

TPM Assessment Tool

The self-assessment available on the Transportation Performance Management (TPM) Toolbox (https://www.tpmtools.org) is available to agencies looking to assess their level of performance management maturity. Three different assessment options are available: a quick, 2-minute assessment, a standard assessment, and an assessment by component of the TPM framework presented in the TPM Guidebook.

TAM Webinar #56 - TAM Tools Miniseries 03: Other Tools

Communities

There are numerous opportunities available for practitioners to interact with people from peer agencies. The following committees and groups provide a way for agencies to share ideas, overcome challenges, and advance asset management practice.

AASHTO

AASHTO is a nonprofit, nonpartisan association representing highway and transportation departments in the 50 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. It represents all transportation modes including: air, highways, public transportation, active transportation, rail, and water. It aims to foster the development, operation, and maintenance of an integrated national transportation system. AASHTO is an international leader in setting technical standards for all phases of highway system development. The website is: https://www.transportation.org.

The AASHTO Committee on Performance-Based Management (CPBM) is dedicated to providing State DOTs the expertise and resources to support performance-based management and to create a results-driven environment to maximize the performance of both transportation systems and organizations. The committee is focused on Organizational Management, Systems Performance, and Federal Policy, Regulations and Programs.

The CPBM’s Subcommittee on Asset Management was created to help improve the State-of-the-practice of asset management in State DOTs. The Subcommittee works to help States optimize resources with performance-based goals and measures for operation, preservation, and improvement of their transportation systems.Transportation

Research Board (TRB)

TRB provides innovative, research-based solutions to improve transportation. TRB is a program unit of the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, a non-profit organization that provides independent, objective, and interdisciplinary solutions. TRB manages transportation research by producing publications and online resources. It convenes experts that help to develop solutions to problems and issues facing transportation professionals, and provides advice through its policy studies that tackle complex and often controversial issues of national significance. The website is: http://www.trb.org/Main/Home.aspx.

TRB Committee on Transportation Asset Management. The Committee seeks to advance the State of the art and State of the practice in asset management. Asset management is a process to strategically manage the transportation system in a cost-effective and efficient manner. Asset management by its nature is a collaborative process, and the Asset Management Committee works with other TRB Committees across all modes, with the AASHTO Asset Management Subcommittee, and other partners.

FHWA

FHWA is an agency within the U.S. Department of Transportation that supports State and local governments in the design, construction, and maintenance of the Nation’s highway system, and various Federal and tribal owned lands. Through financial and technical assistance to State and local governments, the FHWA is responsible for ensuring that America’s roads and highways continue to be among the safest and most technologically sound in the world. The website is: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov.

FHWA TAM Expert Task Group (ETG). TAM ETG was formed as a forum to discuss changes in the way highway agencies are managing assets. The structure and membership of the TAM ETG were intentionally designed to ensure interaction with key AASHTO and TRB committees. Among its objectives, the TAM ETG aims to identify strategies for advancing asset management practice and influencing change within State DOTs and partnering with transportation agencies.

IAM

The IAM is the international professional body for asset management professionals. The IAM develops asset management knowledge and best practice, and generates awareness of the benefits of the asset management discipline for the individual, organizations and wider society. Established in 1994, the IAM has over 22,000 members in 158 different countries. The website is: https://theiam.org.

IAM US Patron Group. The Patrons of the IAM are a special group of Corporate Members who have committed to a high level of activity and engagement with the Institute, and on that basis, have been invited to become a Patron. The Patrons include leading asset managers, who, in exchange for significant support to the Institute, have great influence not only on the development of the IAM itself but also on the development on the discipline.

Gap Analysis Tool Data Structure

This subsection introduces the TAM Gap Analysis Tool designed for agencies to self-assess their Transportation Asset Management (TAM) practices. It outlines the tool's purpose, including comparing practices against industry standards, identifying gaps, recognizing areas for improvement, prioritizing action items, and monitoring TAM maturity over time. The tool operates at three levels—Assessment Areas, Assessment Elements, and Assessment Criteria—covering eight broad topic areas related to TAM practices, each with specific elements and criteria for evaluation during the gap analysis process.

Note: This section was derived from the AASHTO TAM Portal. The TAM Gap Analysis Tool, User Guidance, and additional information are available here: https://www.gapanalysis.tam-portal.com/sign-in/?next=/

Introduction

The Gap Analysis Tool supports analysis at three different levels as shown in the figure and described below.

Figure 1.6 TAM Gap Analysis Tool Demonstration

Level 1: Assessment Areas. The highest level is the Assessment Area, which includes eight topic areas:

- Policy goals and objectives.

- Asset management practices.

- Planning, programming, and project delivery.

- Data management.

- Information systems.

- Transparency and outreach.

- Results

- Workforce capacity and development.

Level 2: Assessment Elements.Each Assessment Area has been subdivided into two or more Elements, which can be considered subsets of each of the eight broad topic areas. The tool supports each element with general recommendations for agency practice improvement, and provides the option to share custom language to support agency user benchmarking decisions.

Level 3: Assessment Criteria. Within each Element, there are two or more criteria that are used to evaluate current and desired practice. Each criterion is presented as a standard statement representing good practice. The tool allows the assessment facilitator to adjust the criterion language as needed to promote understanding by the assessment participants.

During the gap analysis, participants evaluate how closely their agency’s practices match what is described in each criterion. This rating is considered representative of the agency’s current practices. Agencies may also define how closely they want to reflect the practices described in each criterion. This rating represents the agency’s desired practices. The difference between the current and desired practices determines whether a gap exists.

The number of Elements and Criteria within each of the eight Assessment Areas are shown in the table below.

Table 1.1 Assessment Areas of TAM GAP Analysis Tool

| Assessment Areas | Elements and Number of Criteria |

|---|---|

1: Policy Goals and Objectives |

|

2: Asset Management Practices |

|

3: Planning, Programming, and Project Delivery |

|

4: Data Management |

|

5: Information Systems |

|

6: Transparency and Outreach |

|

7: Results |

|

8: Workforce Capacity and Development |

|

Using the Tool

This subsection introduces the TAM Gap Analysis Tool designed for agencies to self-assess their Transportation Asset Management (TAM) practices. It outlines the tool's purpose, administration process, and the flexibility it offers in tailoring assessments to agency needs. Additionally, the document provides a checklist suggesting strategies for addressing identified gaps and advancing agency practices based on the gap analysis results across different TAM focus areas.

Note: This section was derived from the AASHTO TAM Portal. The TAM Gap Analysis Tool, User Guidance, and additional information are available here: https://www.gapanalysis.tam-portal.com/sign-in/?next=/

Overview

A gap analysis is administered by an individual within the agency who is responsible for identifying participants, determining what part of the assessment each participant will receive, distributing links to the assessment to each participant, and compiling the results. As detailed in the User’s Guide, the TAM Gap Analysis Tool provides agencies flexibility in using the survey as it’s designed, or reducing the survey length by eliminating Elements or Criteria that may not be relevant. There is also flexibility in determining which parts of the assessment are appropriate for each participant. For instance, individuals associated with data collection may only be asked to evaluate the criteria related to Assessment Area 4, Data Management.

Individualized links are distributed to each participant to complete the assessment. Assessment participants are required to log into the web-based tool (using their email address). Once logged in, the participants are able to access the assessment, where they are asked to rate the agency’s current practices in comparison to each Criterion using a 5-point rating scale. Optional fields are provided for notes that a participant may want to make to explain their response. In addition to rating the agency’s current practices, the tool allows the agency to set a desired, or targeted, rating for each criterion using the 5-point scale.

After all assessments are completed, the results are compiled and presented as graphs, spider diagrams, and tables. Results can be compiled at the agency level or by any subset of the raters. Results can also be presented at the Assessment Area, Element, or Criteria level depending on the agency’s needs. To facilitate reporting, results can also be exported in spreadsheet format for external reference and use.

Additional details on administering the assessment and interpreting the results are available in the User Guide: https://www.tamguide.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/GAP-Analysis-Tool-User-Guidance.pdf

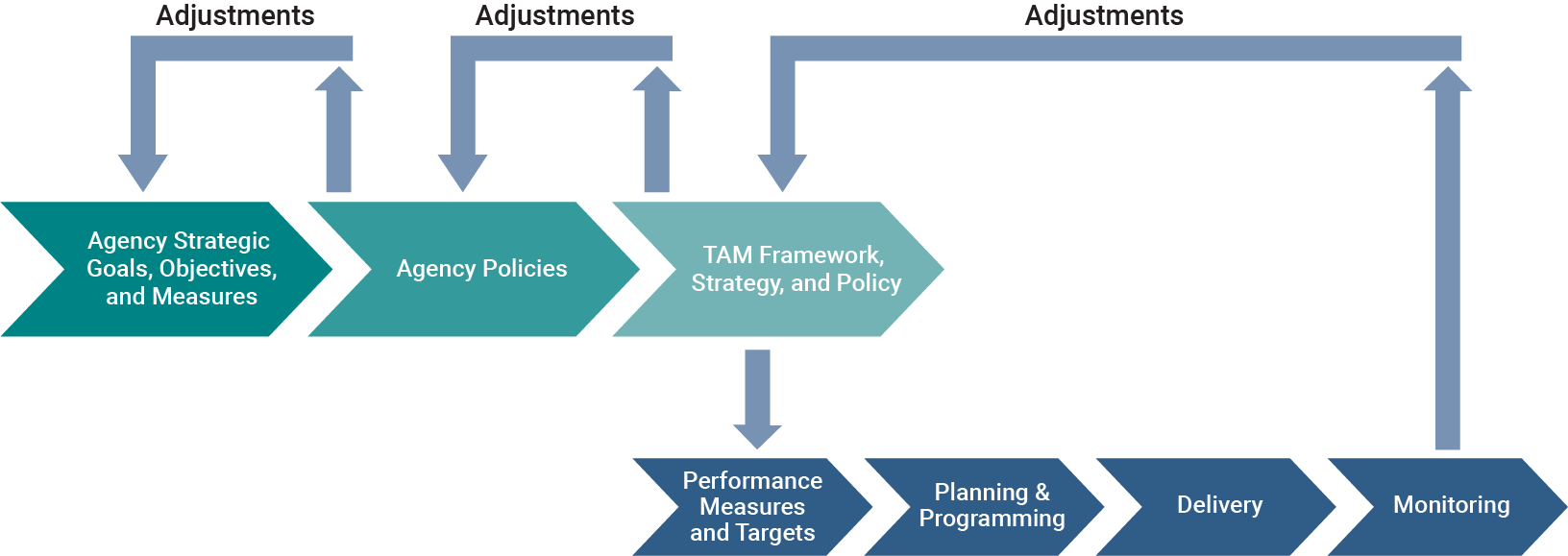

Integrating TAM Within Agency Strategic Plans and Policies

Integrating TAM within existing strategic documents is key to ensuring TAM is established and sustained.

Overview

TAM Webinar #34 - Integrating PM2 Targets with the TAMP

TAM is not a stand-alone practice that is only applicable to select areas of a DOT. Ideally, TAM principles and practices should be integrated within an agency's vision, mission and strategy documents (see Figure 2.1). TAM promotes accountability, preservation, data-driven decision-making and the optimization of resources; all of these are broader strategic goals often outlined in plans and policies other than a TAMP. Aligning TAM with the agency’s strategic documents helps ensure an agency's vision is all encompassing and cohesive.

These documents include:

- Agency-wide strategic plan and/or business plan (including long-range plans)

- Agency-wide financial plan

- State long-range plan

- Other performance plans (safety, mobility, freight, etc.)

In addition, some agencies may choose to adopt a TAM policy with principles that the agency will follow. A TAM policy can be used to communicate the purpose of TAM and build understanding and support for TAM within the agency. It can also help to sustain a TAM approach through leadership changes. See the next section for further information on creating a TAM policy.

TIP

'Line of Sight' is a concept that describes alignment of an agency's asset management practice to its strategic goals and business objectives.

Michigan DOT

MDOT’s strategic plan has seven strategic areas of focus. A key focus area is System Focus, which aims to provide cost-effective, integrated and sustainable transportation solutions. The first strategy under this focus is to “apply asset management principles to prioritize and implement the most cost-effective transportation investment strategies.” This connection between MDOT’s strategic plan and their TAM program communicates the importance of asset management in how the agency conducts business. It gives TAM a seat at the agency-wide strategic plan monitoring sessions and allows for the resources needed to carry out TAM activities.

Source: Michigan DOT. 2017. MDOT Strategic Plan. https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdot/MDOT_2017_StrategicPlan_553573_7.pdf

Integration Management

Integrating Effective Performance, Risk, and Asset Management

Creating a TAM Policy

A TAM policy describes the adoption of asset management principles for managing infrastructure. It defines the intent of the TAM program and can include how TAM will be carried out in the agency. Leadership direction on the policy helps achieve buy-in throughout the agency, making it easier to ensure it connects to and aligns with other strategic documents.

Strategic Framework for Asset Management

A TAM policy can be the first place an agency communicates the strategy of their TAM program. It can be thought of as a contract between the agency and its customers, partners and stakeholders that defines how TAM fits within the agency's decision making process.

Some elements of a TAM Policy can be included within a TAMP (TAM Objectives, Scope of TAM, connection of TAM to other planning initiatives, and TAM roles). However, a separate TAM Policy may provide those responsible for TAM within an organization the ability to challenge existing processes and approaches. A concise TAM Policy defines the principles that guide the decisions made during TAMP development and implementation.

A TAM Policy can outline the types of assets considered for management and identify where in the cycle of DOT work activities to emphasize asset management practices. It can also establish the high-priority initiatives on which the agency will focus their efforts. A TAM policy starts to set boundaries and clarify the intent of asset management.

A TAM policy may include:

- Definitions of services provided to customers and distinctions between service levels

- Approaches for managing assets from a whole life perspective

- Decision-making standards, based on the triple bottom line (economic, environmental, and social)

- Consideration of risk

- Approach for making transparent, data- driven decisions

For further details on developing a TAM Policy, see the how-to guide in this chapter.

Oklahoma DOT

The Oklahoma DOT identified the following TAM objectives to help guide their asset management program:

- Maintain (improve) the condition of the state’s bridges and roadways

- Reduce risk associated with asset performance

- Make better data driven decisions about assets

- Reduce costs and improve efficiency, including effectively delivering projects that support asset management

- Increase internal and external communications and transparency

- Improve customer service

- Improve safety on the state’s transportation system

- Enhance mobility of people and goods

TAM Goals, Objectives, Strategies

TAM goals and objectives support and communicate the policy and align with the broader agency vision, mission, goals and strategies. Goals and objectives may cover transportation system performance and desired outcomes, as well as agency decision-making approaches and practices. Some agencies have goals and objectives, while some have only goals and others have only objectives. Regardless of the terminology that is used, it is important that agencies set a vision and establish a direction to move towards. The Oklahoma DOT practice example highlights their TAM objectives.

Agencies should include a clear statement of TAM principles – either within the agency’s strategic documents or as a stand-alone policy. They should also seek opportunities to strengthen the integration of TAM within the agency’s strategic planning efforts.

TIP

A TAM Policy can be a sign of leadership commitment to implementing asset management. A good policy is clear, concise, and easy to interpret.

Ingredients for Success in Creating a TAM Policy

The following are some of the key ingredients that make a TAM policy successful.

Leadership Support

Leadership support and direction in the effort to create a TAM policy is important. Effective leadership ensures and maintains a connection across the various types of goals. A typical transportation agency has a lot of moving parts and multiple, sometimes conflicting, priorities. The nature of TAM and its success in meeting TAM goals involves actions that cut across individual business units. Leadership is a critical ingredient in creating positive change and maintaining processes across business units. See section 3.1 for more information on leadership.

Internal and External Stakeholder Engagement and Support

Involving groups and people who want a voice in the TAM program’s success, whether external partners or stakeholders or internal business units, is important for creating policies that will have a positive impact and are sustainable. See section 3.2 for more on stakeholder engagement.

Consider Implementation

There may be multiple ways to accomplish policy objectives, so the policy should be simple and flexible rather than complex and rigid.

Link to Performance Management

Performance management is an underlying component of good asset management. Policies should consider the ability to define performance measures, collect data and measure performance. They should also consider the cycle of setting objectives, monitoring performance and making adjustments. See section 2.2 for more on TAM performance and monitoring.

Amtrak

Amtrak’s Engineering Asset Management policy identifies guiding principles that the agency intends to use in managing the infrastructure it owns and maintains. Specifically, the policy focuses on developing asset management capability and implementing the TAMP. The policy begins with a purpose statement that defines asset management, and then lays out seven principles (or standards) to guide asset management practice. The principles highlight ownership, transparency, risk management, life cycle costs and information systems standards for Amtrak’s asset management practice. In addition, the policy also identifies responsibilities and leadership commitment, calling out specific positions in the agency and their role in delivering the asset management plan. The policy is included as a section in their asset management plan and is signed by the President and CEO, EVP Chief Operating Officer, and VP Chief Engineer.

TAM Principles

FHWA Principles of Asset Management

FHWA has defined a number of basic principles for asset management as listed below. All of these ideas work together to help an agency make decisions to better address their infrastructure needs. Asset management should be:

Policy driven. Decisions reflect policy goals and objectives that define desired system condition and service levels.

Performance based. Performance information is used to establish target levels, to allocate funding, and to monitor progress.

Risk based. Risk management is used to identify, analyze, evaluate and address the risks to assets and system performance.

Option oriented. Comprehensive choices and trade-offs are examined at each level of decision making.

Data driven. Management systems and tools that utilize quality data are used to support decisions.

Transparent. There are clear criteria for making decisions.

Seattle DOT

Seattle is one of the fastest growing cities in the U.S. and the demands on the transportation system have grown dramatically. Meanwhile, the system is aging. Seattle DOT (SDOT) needed to find a way to balance infrastructure expansion, preservation, and maintenance by aligning its Asset Management practices with its service delivery strategies. All of this had to occur within the limits of available resources and ensure that SDOT strategically managed the transportation system for years to come. SDOT’s Asset Management initiative provides a long-term vision of how SDOT intends to accomplish its mission. In 2007, the SDOT began implementation of Asset Management, a strategic and systematic process that guides decisions about construction, maintenance, and operation of SDOT infrastructure. The SDOT identified and adopted the following three key principles of asset management principles:

- Build, preserve, and operate transportation infrastructure services more cost effectively with improved asset performance;

- Deliver to customers the best value for public tax dollars spent; and

- Enhance the credibility and accountability of SDOT to the Mayor and City Council

These principles were intended to identify the outcome of a fully implemented asset management program at SDOT. They are supported by a longer list of asset management principles (https://www.seattle.gov/transportation/about-sdot/asset-management) and an Asset management Policy that identify the areas of focus. The Policy highlights the steps SDOT intends to take recognizing that achieving the key principles is a long-term effort achieved through continuous improvement.

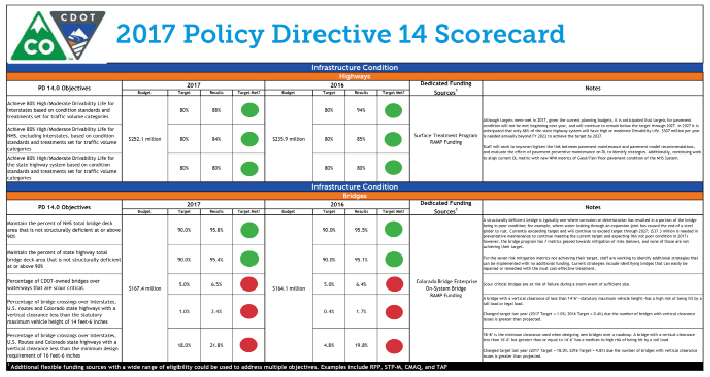

Colorado DOT

In 2015, the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) updated Policy Directive 14 (PD 14.0) “Policy Guiding Statewide Plan Development” to reinforce the importance of TAM in the transportation budget allocation process. It includes the following objectives:

- Infrastructure Condition – Preserve the transportation infrastructure condition to ensure safety and mobility at a least life cycle cost

- Maintenance – Annually maintain CDOT’s roadways and facilities to minimize the need for replacement and rehabilitation

Embedded in this policy are target-setting requirements that the Transportation Commission requested. A performance tracking mechanism is tied to this policy directive. This performance management focus is reinforced annually in a PD14 workshop hosted by the Transportation Commission where the most recent performance results are presented.

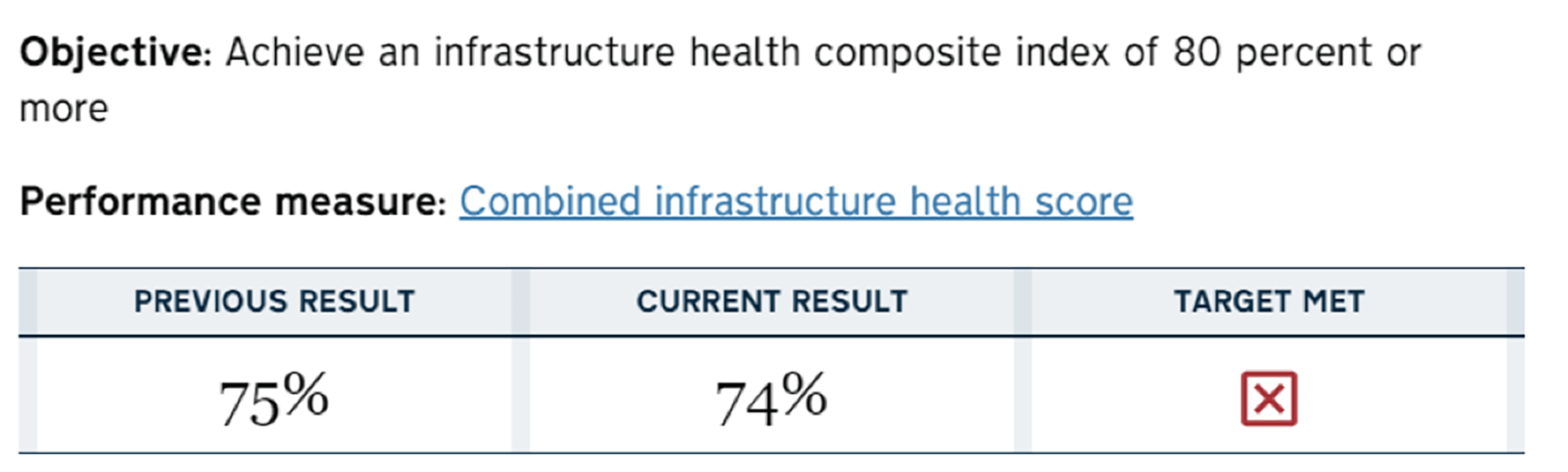

Source: Colorado DOT Scorecard, 2017.

IPWEA

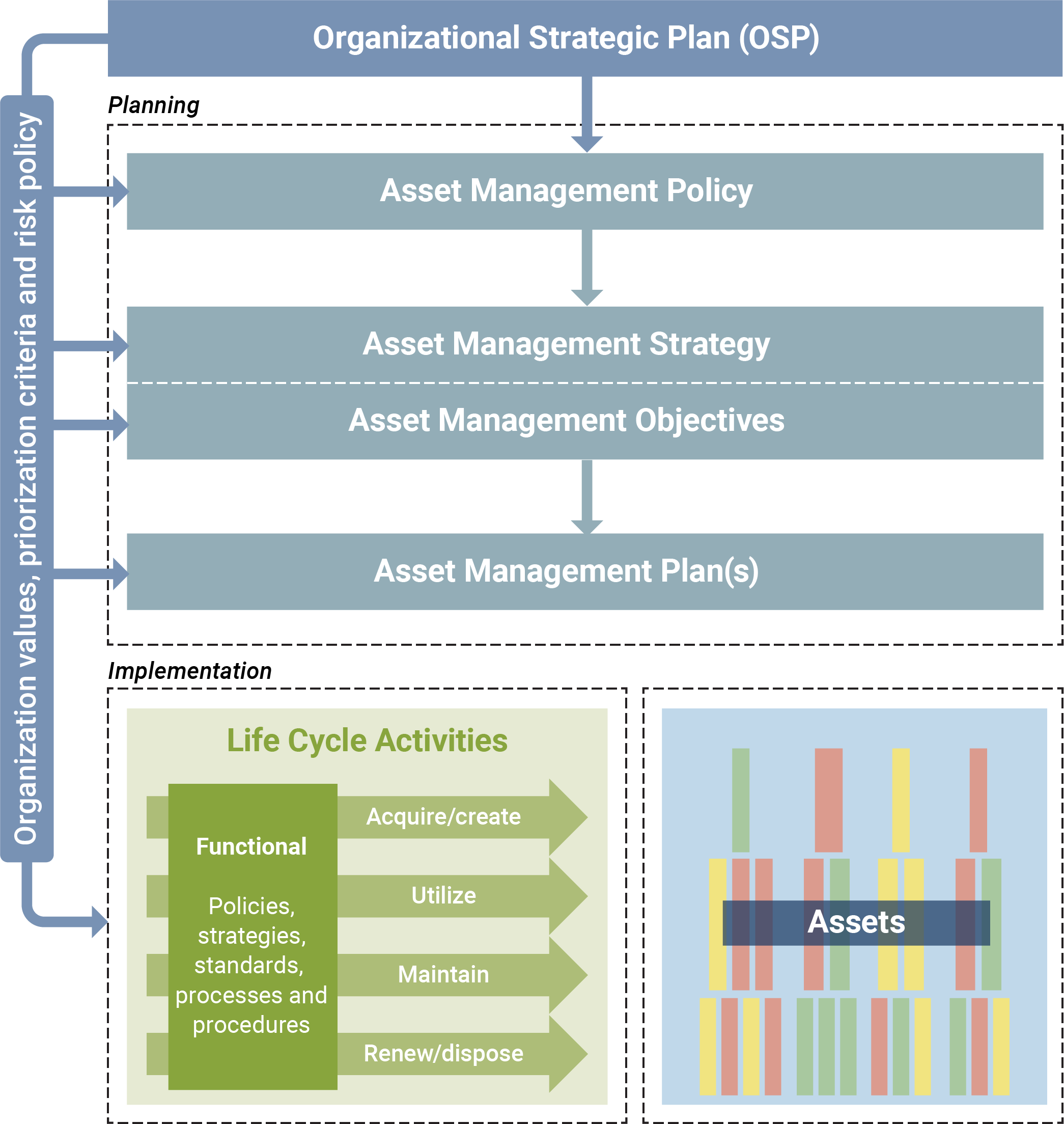

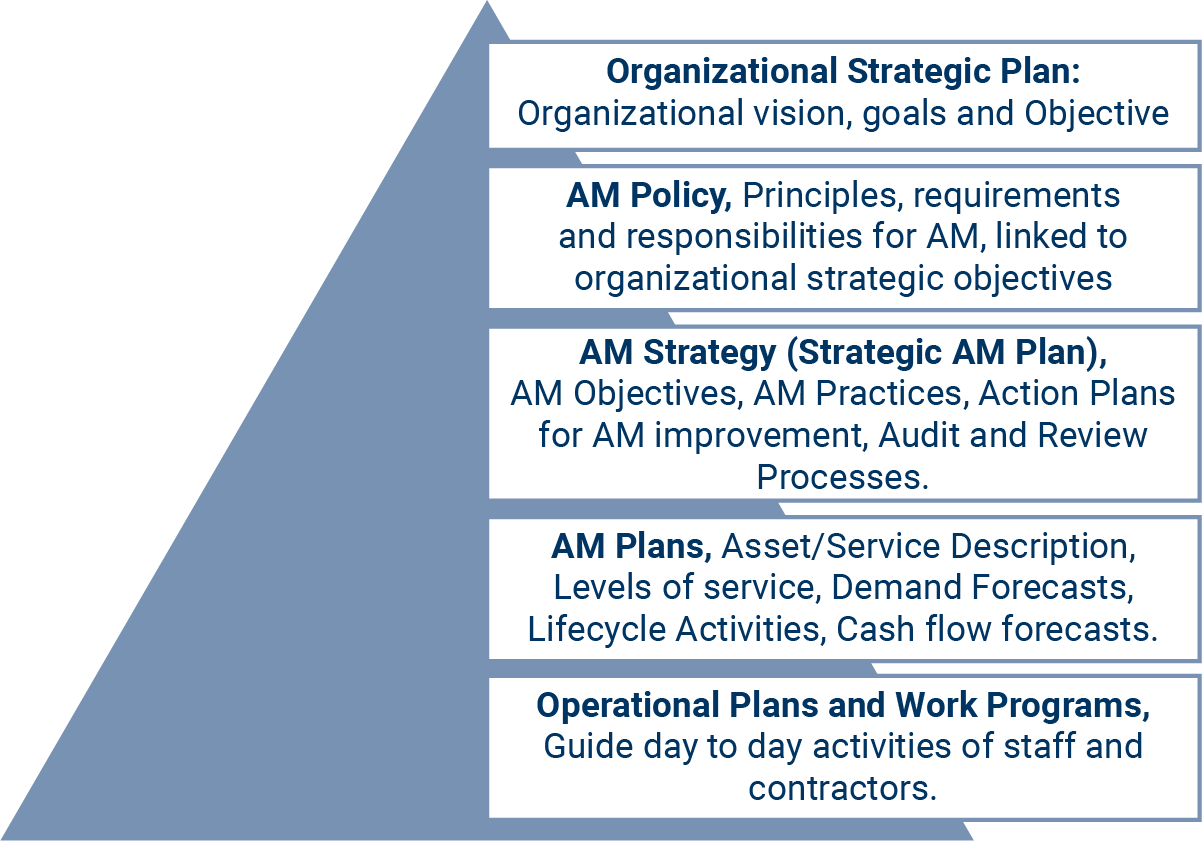

ISO 55000 adopts the concept of an Asset Management System, as the figure at right illustrates, which typically consists of several components:

- An organizational strategic plan that set the overall context

- An asset management policy establishes the principles on which the agency makes decisions associated with the management of and investment in infrastructure. It seeks to link the organizational goals and objectives to the principles for management of the infrastructure portfolio.

- The Asset Management Strategy, (sometimes termed the Strategic Asset Management Plan or SAMP) establishes how the agency overall will implement asset management and implement the AM Policy. It articulates a framework of how management processes will function in managing infrastructure and delivering services, as well as how the agency will continuously improve their asset management practices over time.

- Asset management plans developed for individual asset classes (pavements, bridges, ancillary assets) are focused on their individual portfolios. However, they align with the overall agency strategy and are customized to the level of management required.

- Operational plans and work programs guide routine activities and have a line of sight to overall agency goals in this structure.

Within the ISO structure, the TAM framework includes these components but each component may vary in scope. For example, the SAMP may require all asset classes to forecast demand, establish service levels and have performance indicators, but compliant sub-asset management plans may have different levels of complexity. A bridge asset management plan may be more robust than one for network culverts. The agency can select the scope and structure appropriate for each aspect within the portfolio.

Asset Management System Components

Source: Institute of Public Works Engineering Australasia. 2015. International Infrastructure Management Manual (IIMM). https://www.ipwea.org/publications/ipweabookshop/iimm

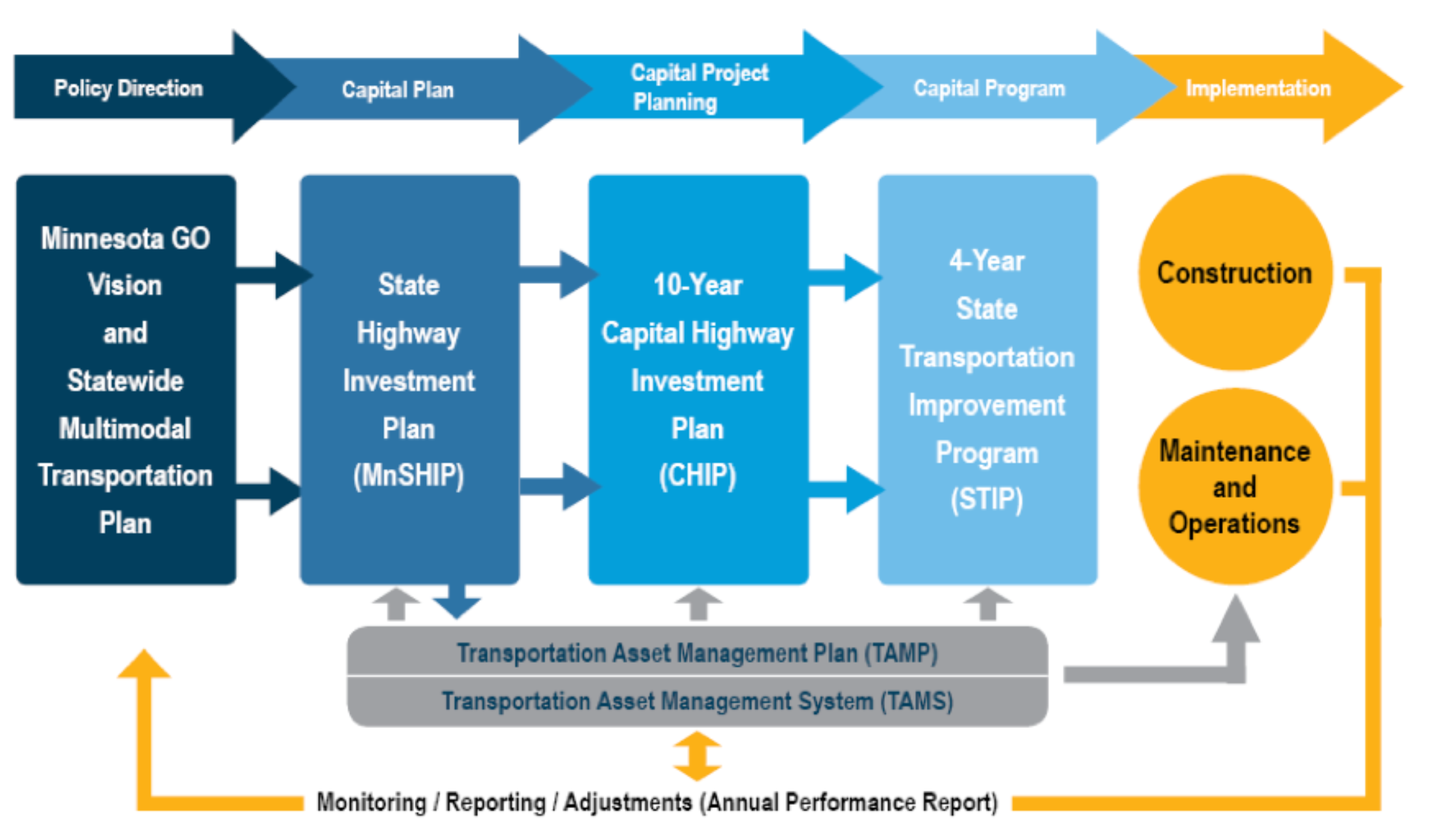

Planning and Programming

Linking and aligning asset management with planning and programming activities helps strengthen an agency's delivery of projects. Planning and programming processes set strategic direction and resource allocation practices; TAM helps set priorities and encourages data-driven, performance-based decision-making.

Using the TAMP Approach to Look at Demand Scenarios

Planning is the process of setting strategic direction through goals and objectives, then performing analysis to identify trends, strategies, and long-term investment priorities. Planning answers the questions of where to go and how to get there. Programming involves allocating resources in order to determine a program of projects the agency will pursue. Planning and programming are central to the work of any transportation agency. Integrating TAM into the planning and programming process will only strengthen and sustain the practices involved in both areas.

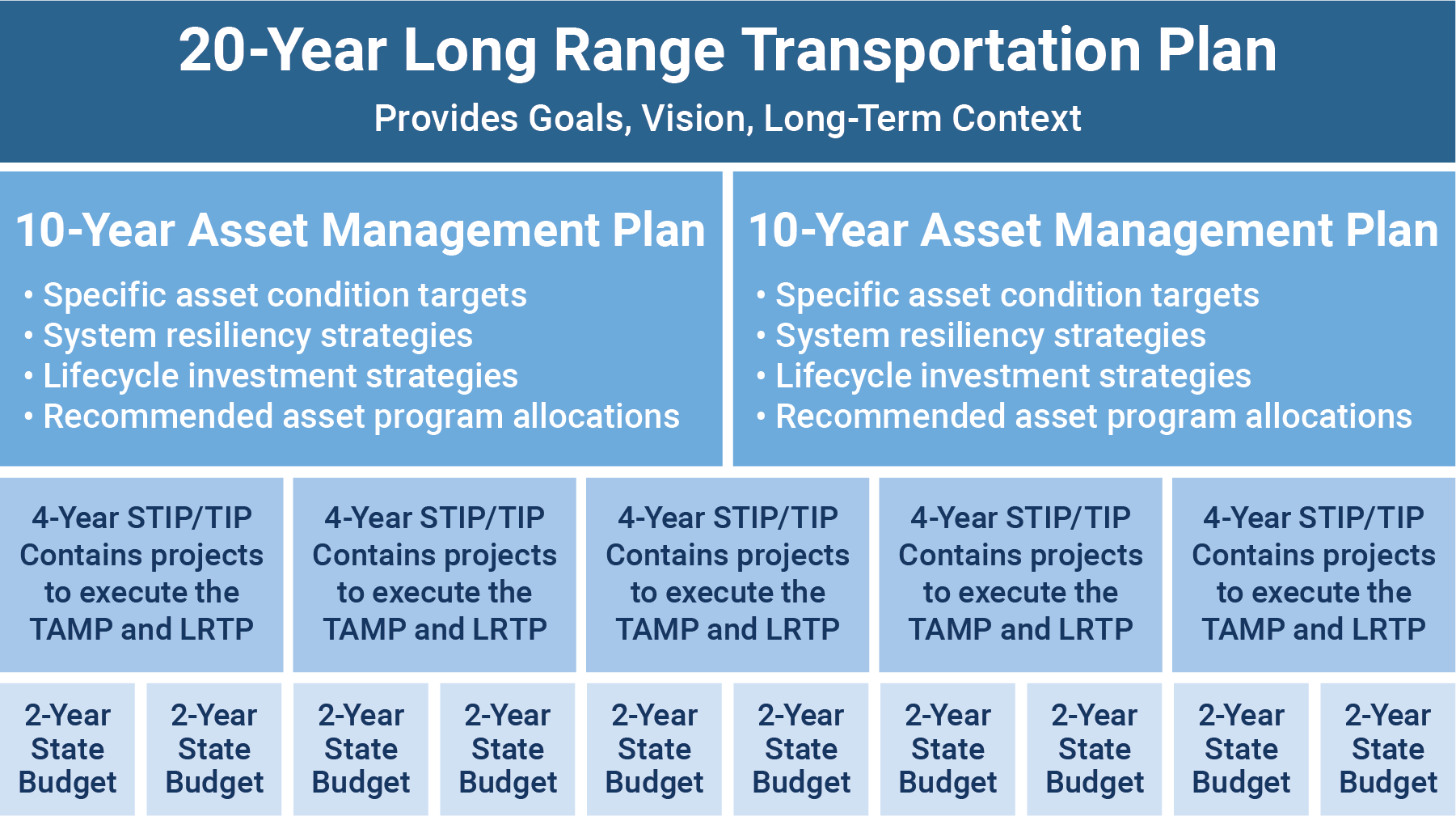

Developing the Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) and the Statewide Transportation Improvement Plan (STIP) are two planning activities where the integration of TAM is especially relevant.

TAM principles, data and tools can help shape the LRTP and STIP by:

- Linking agency resource allocation to policy objectives.

- Defining the performance targets to be achieved.

- Identifying strategic investment choices and evaluating and analyzing tradeoffs among them at the appropriate stages.

- Providing the information and analyses to facilitate the appropriate resource allocation decisions that follow good TAM practice.

Integrating TAM approaches with planning and programming goes beyond informing and shaping the activities. Communication and coordination between activities and the people involved in them is important as well. Both planning and TAM require an understanding of the life cycle of an asset. This requires coordination with operations teams to communicate how decisions impact the expected useful life of the asset. Operations teams also need to be aware of the asset management planning horizon, performance measures and targets. These teams need to ensure the capital plan has been accounted for in the maintenance and operational plans. In addition, since planning is a network-level endeavor, teams managing each of the different asset types need to communicate with one another and coordinate with planning.

The following are some key questions to ask when considering the integration of TAM with planning and programming.

- Is the cost of maintenance and operations taken into account in the decision-making process to select capital projects?

- Are there mechanisms to directly evaluate tradeoffs between capital investment and operations and maintenance implications within the planning process?

- Are the needs and implications associated with connected and autonomous vehicles considered in the asset management plan?

- Are future risks such as climate change fully integrated into the capital planning process (rehabilitations, renewal, service level upgrades, etc.)? Is scenario planning used to assess the risk effects of system wide external changes?

TIP

TAM practice is most effective when linked to planning and programming activities; this is one way to ensure that TAM principles are implemented into agency decision making.

The FHWA Asset Management Financial Report Series, Report 4 Integrating Financial Plans into the Planning, Programming, and Budgeting Processes describes the importance of integrating planning, programming, and budgeting with asset management.

The relative timeframes of various planning and programming activities is shown in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2 The Relative Timeframes Between Plans

Long-range plans, asset management plans, TIPs, and state budgets should be aligned.

Source: FHWA, 2017. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/asset/plans/financial/hif16001.pdf

TIP

Involving internal and external stakeholders in the TAM process early can encourage or enhance their buy-in when the time comes to make important decisions.

Montana DOT

When developing their 2018 TAMP MDT aligned their pavement performance targets and goals to those within their planning document TranPlan 21 (now TranPlanMT). TranPlanMT defines MDT's policy direction for operating, preserving, and improving Montana’s transportation system over a 20-year period. It serves as the guiding document for MDT decisions, especially those related to investing Montana’s limited transportation funds. This type of alignment can help illustrate a link from policy objectives to investment strategies and resource allocation.

Sources:

Video Overview of Planning TAM

Integrating TAM Into the Planning Process

The FHWA TAM Expert Task Group produced the following video to explain how to integrate TAM into the transportation planning process.

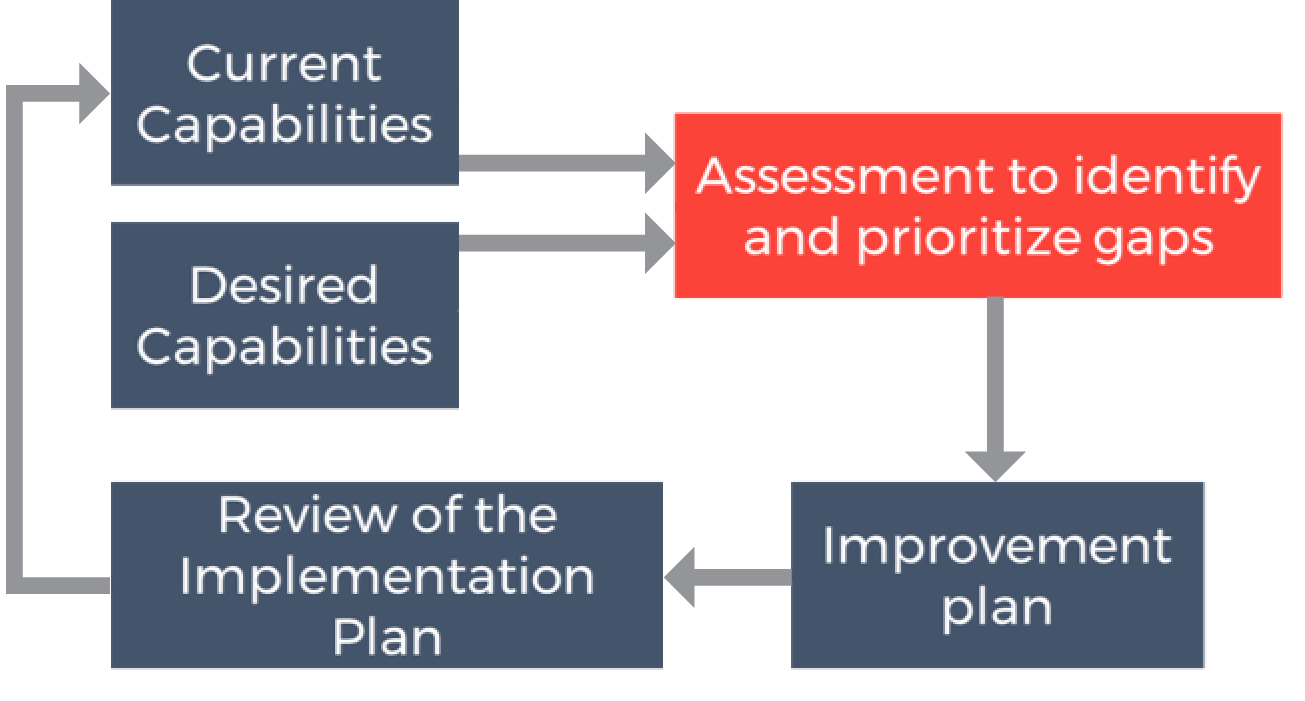

Assessing Current Practice

An assessment of current agency competency against industry-leading practice enables an agency to assess a desired future performance level. It can also help to identify the steps required to reach that goal.

TAM is an evolving process; ongoing improvement is an important component for a TAM program. In fact, the ISO 55001 Asset Management certification requires ongoing assessment and continual improvement.

A gap assessment process is used to understand how well an agency aligns with an established asset management framework. The gap assessment can be conducted internally or by a third party. Organizations seeking or wanting to maintain ISO certification will also undergo a formal third party audit.

The results of a gap assessment can help agencies identify changes in business processes needed to better link plans and decisions and better align to leading practice.

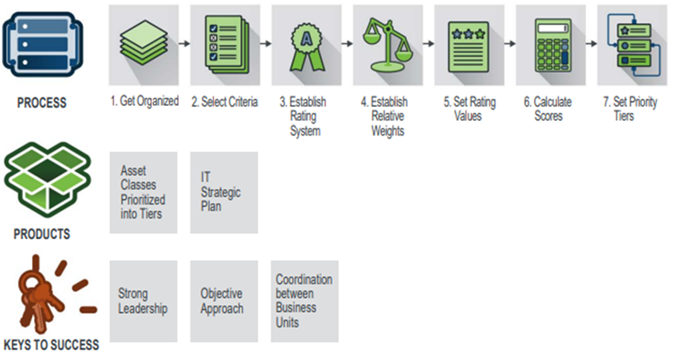

NCHRP Project 08-90 led to the development of a gap analysis tool, available through AASHTO and the TAM Portal. Figure 2.8 illustrates how this assessment tool is intended to be used. There are several other frameworks that can be used, including ISO 55001 and the Institute of Asset Management (IAM). A range of gap assessment framework’s are discussed further in Table 2.1. Each framework, process or tool will enable an agency to assess current performance and, from this, identify a desired capability level.

Figure 2.8 TAM Improvement Cycle

Source: Modified from original in NCHRP Project 08-90

TIP

Factors to consider when prioritizing advancement in TAM approaches will vary from agency to agency. Consider those factors that are of most importance to you and are well-aligned to your strategic goals.

In some cases, agencies also seek benchmarks that reflect how peers are performing to help them decide on the level of maturity and complexity to which they should aspire. ISO 55001 trends away from this. It encourages agencies to check against a framework of practices and process, and select what is best for the agency. Chapter 6 addresses benchmarking and related topics.

Actions to close gaps between desired and actual performance should be addressed within a TAM improvement or implementation plan.

Undertaking a gap assessment can form an important part of a change management process by aligning those within the agency on current performance, opportunities and targets for improvement.

Table 2.1 - Frameworks for Assessing Current Practice

| Framework | NCHRP 08-90 Gap Analysis Tool | ISO 55001 Asset Management Gap Analysis | International Infrastructure Manual (IIMM) | IAM Self-Assessment Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | This tool was developed based on the tool and process created through development of the 2011 AASHTO TAM Guide. Uses a point scale for evaluating current and desired capabilities. See more | This is the most widely adopted standard for asset management globally. It is generic to accommodate many contexts. Describes a management system approach to asset management. See more | Recognizing that the ISO Standards for asset management are very much the “What to do”, the IIMM looks to provide the “How to do it”. Identifies an Asset Maturity Index (Aware, Basis, Core, Intermediate, Advanced) to identify the current and an appropriate level of asset management for each asset. See more | As an aid to the application of ISO 55001, the IAM decided to update their methodology into one that enables organizations in all sectors to measure their capabilities against the requirements of both PAS 55 and ISO 55001. See more |

| Assessment or Focus Areas |

|

|

|

|

| Why use this framework? | This framework is best for an agency that wants to work explicitly within a US-defined context that adopt wider influences. Since this tool can be fully customized by an agency, an agency that wants to tailor the analysis to their particular needs will find this useful. Finally, the tool facilitates the analysis of data, and can generate graphs and charts using the data imported into it. | This framework is ideal for agencies that want to adopt a world-recognized approach to asset management that provides a developed asset management lexicon. This is currently the most internationally-recognized standard in the world. | This framework has been refined over time with many examples that illustrate successful application of concepts by organizations. Public agency focused, and largely written for the asset management practitioner responsible for civil assets. | This standard is well recognized internationally, is infrastructure agnostic, and has applicability to infrastructure owners in both the private and public sector. It has many other resources developed along with the framework including training materials, reference guides and courses to upskill an agency. |

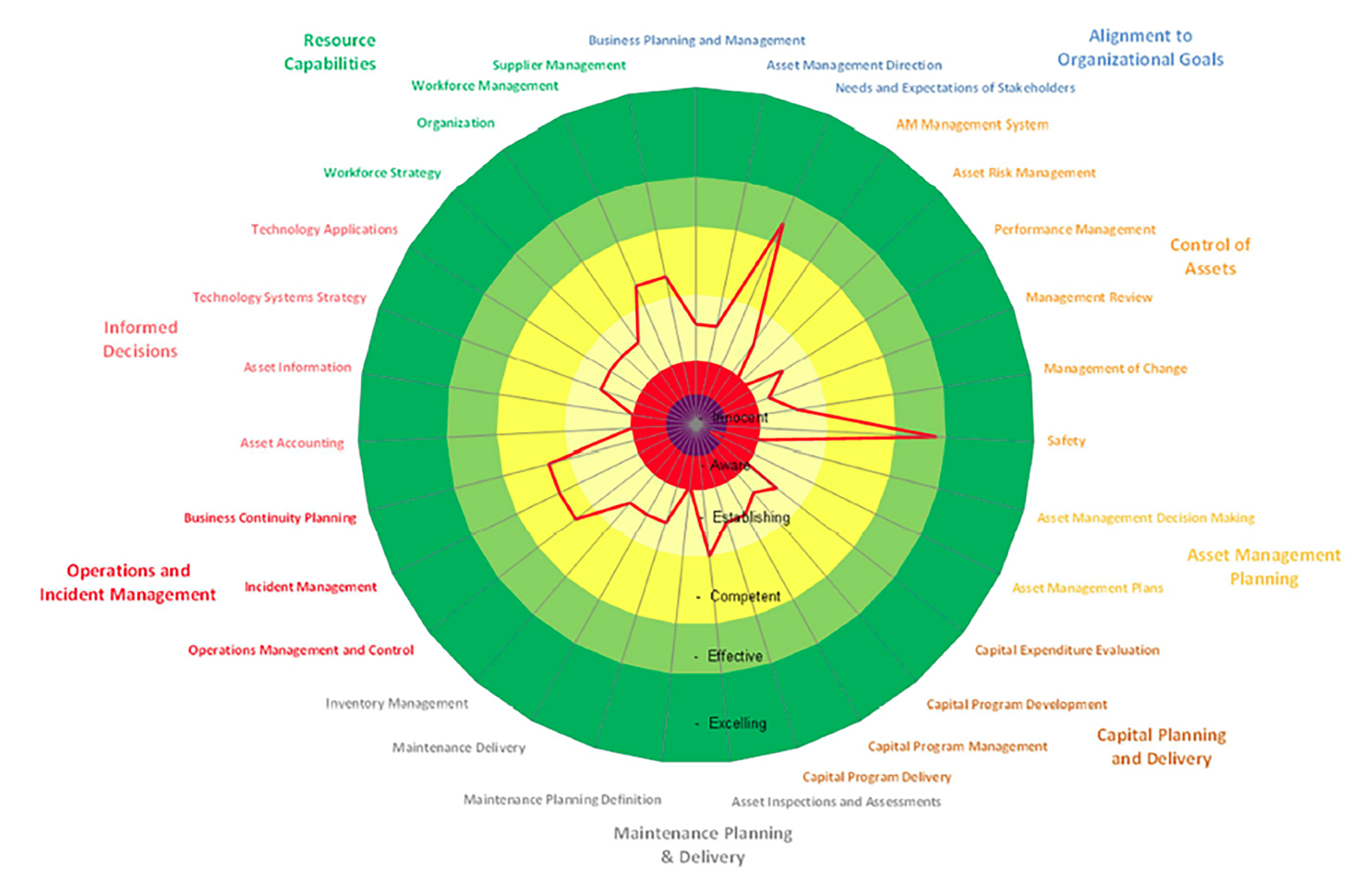

Amtrak

In 2016, Amtrak Engineering undertook an Asset Management Capability Assessment which bases maturity on the degree of formality and optimization of processes. The assessment uses several questions grouped into eight assessment areas, which describe operational processes necessary for asset management success. This maturity methodology is aligned with emerging guidance from the Institute of Asset Management (IAM), ISO 55001 standards, and requirements of the US FAST Act.

The assessment used a six-point scale, scoring Amtrak at the Establishing level, indicative of an agency that is actively developing asset management capabilities and establishing them to be consistent, repeatable, and well-defined.

Based on the 2016 assessment results, key challenges were identified and a series of improvement recommendations were developed and integrated into an Asset Management Improvement Roadmap.

In addition, Amtrak established a target position, driving process implementation priorities, with the intention of continuous monitoring by repeating the capabilities assessment process on an annual basis.

2016 Amtrak Asset Management Capabilities Assessment Results

Source: Amtrak Engineering 2019

The Basic TAMP

A TAMP describes an agency’s goals and objectives for maintaining its assets over time. It describes an agency’s most critical assets, and their current condition. It also describes the agency’s strategy for preserving its assets, predict future conditions given the agency’s planned investments, formulate and deliver an investment plan, and discuss how the agency manages risks to its assets.

TAMP Requirements

TAM Webinar #58 - The 2022 TAMPs & BIL Requirements

This section discusses the requirements for a TAMP that is consistent with TAM leading practice. A TAMP includes:

- TAM Policies, Goals and Objectives

- Asset Inventory and Condition

- Life Cycle Planning Approach

- Predicted Asset Conditions

- Investment Plan

- Risk Management

Note there are additional specific requirements for a TAMP that is prepared to comply with Federal requirements. State DOTs are required to prepare a TAMP with a 10-year horizon that includes, at a minimum, NHS pavements and bridges. Transit agencies that receive Federal funds are required to prepare a TAMP with a four-year horizon that includes their revenue vehicles, facilities, infrastructure, and equipment (including service vehicles). FHWA provides a checklist of elements of TAMPs compliant with Federal requirements: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/asset/guidance/certification.pdf. A similar FTA document is available at: https://www.transit.dot.gov/TAM.

TAM Webinar #35 - Developing the Complete TAMP

TAM Policies, Goals, and Objectives

A TAMP summarizes an agency’s policies, goals, and objectives and describes how its approach to TAM helps support these. For instance, the document might discuss how maintaining assets in good repair supports the organization's broader goals for strengthening mobility and supporting economic development. It may also describe how the organization defines the desired state of repair of its assets, or criteria for evaluating whether or not an asset is in good repair. A clear linkage between TAM objectives and the achievement of wider agency goals should be directly illustrated within the TAMP.

TIP

The biggest benefit of developing a TAMP can come from the process as opposed to the product itself. Developing a TAMP can give agency staff a greater awareness of what assets they own, what condition they are in, and how their performance can be influenced by factors and decisions in other parts of the agency.

TAM Webinar #46 - Improving Your Next TAMP Miniseries: Overview

Asset Inventory and Condition